Publication of this book was supported in part by a grant from the Baldridge Book Subvention Fund through the Humanities Institute of the College of Humanities and Sciences at the University of Montana.

2019 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jabour, Anya, author.

Title: Sophonisba Breckinridge: championing women's activism in modern America / Anya Jabour.

Description: [Urbana, Illinois] : University of Illinois, [2019] | Series: Women, gender, and sexuality in American history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005786 (print) | LCCN 2019009631 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252051524 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252042676 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252084515 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Breckinridge, Sophonisba P. (Sophonisba Preston), 18661948. | FeministsUnited StatesBiography. | FeminismUnited StatesHistory19th century. | FeminismUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Women social workersUnited StatesBiography. | Women social reformersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC HV40.32.B73 (ebook) | LCC HV40.32.B73 J33 2019 (print) | DDC 305.42092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005786

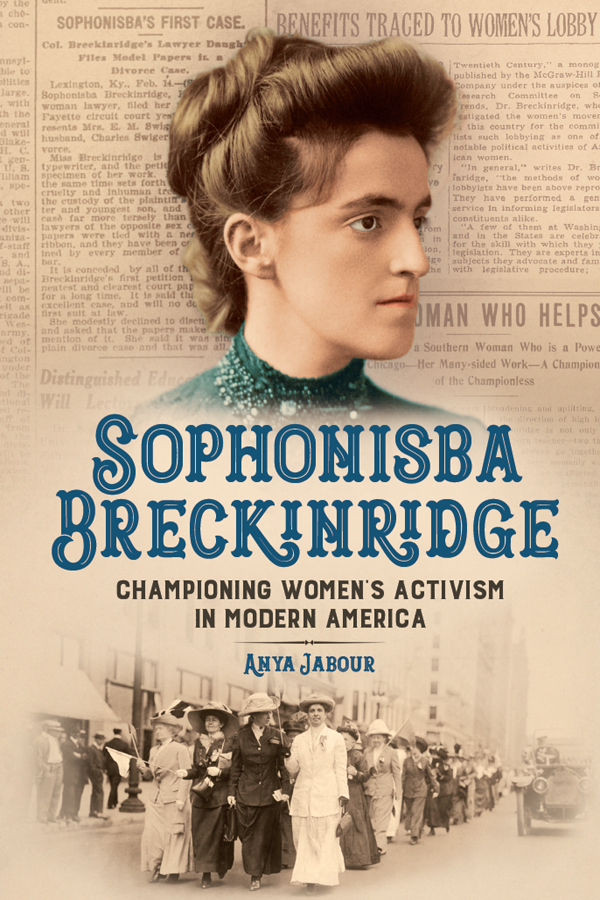

Cover illustration: Sophonisba Breckinridge, ca. 1880s (Wellesley College Archives). Background: Women delegates to the Progressive Party National Convention in Chicago, 1912 (State Library of New South Wales).

PREFACE

Forgotten Feminist

In 1933, Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge responded to a young woman's request for career advice by suggesting that she contact Democratic Party insider Mary W. Dewson, known as More Women Dewson for her success in placing women in New Deal positions. She is a good feminist, commented Breckinridge, which simply means that she wants good women to have their chance. Breckinridge, too, was a good feminist throughout her long life, from 1866 to 1948. Nationally and internationally renowned in her lifetime, since her death in 1948 Breckinridge has been largely forgotten. This bookthe first comprehensive biography of this forgotten feministreclaims Breckinridge from historical amnesia and offers fresh insights into women's activism in modern America.

I didn't set out to write a biography of Breckinridge. I have a longstanding interest in exploring personal lives in historical context: My first book was a case study of a married couple; my second and third books included cameos of individuals; and I have published numerous articles featuring case studies of individuals, families, and circles of friends. Nonetheless, when I discovered Breckinridge, it was by chance. In 2009, in the course of conducting background research for a planned book project on women teachers in the Victorian South, I came across a short biographical profile of Breckinridge. I was immediately intrigued to learn that, despite earning advanced degrees in politics, economics, and law, she was unable to find an academic position in any of her fields of specialty.

As I learned more about Breckinridge, I was intrigued to find that she responded to the limited professional opportunities available to women by pioneering a new, female-friendly profession: social work. This discovery prompted me to reexamine my assumptions about feminized occupations, especially when

Breckinridge's background as well as her accomplishments interested me. How had this privileged daughter of one of the leading families of the Southern Confederacy come to be an outspoken advocate for African Americans, immigrants, and the working class? What family influences and childhood experiences had paved the way for an elite white woman to become, as one laudatory profile in the Woman's Journal put it, a champion of the championless?

Breckinridge's personal relationships with other professionally successful and politically powerful womenAlice Freeman Palmer, president of Wellesley College; Marion Talbot, dean of women at the University of Chicago; Jane Addams, head of Hull House; Julia Lathrop, chief of the U.S. Children's Bureau; and Edith Abbott, dean of the University of Chicago's School of Social Service Administration, among many othersalso caught my attention. What role did female friendship play in defining Breckinridge's life's course?

My curiosity was piqued. I wanted to know more about this remarkable woman, but I found myself frustrated by a lack of scholarship about her. Sociologists and social workers had written a handful of articles about her, and historians occasionally included her in broader discussions of social reform and social work education, but nobody had attempted a comprehensive study of her life and work. I found that, despite her long association with Jane Addams and Progressive reform, books on these subjects routinely omitted Breckinridgeor, if they included her, they misspelled her name. In addition, I discovered that while Breckinridge reached the height of her influence in the 1920s and 1930s, extant treatments of her careerlike studies of progressivism and feminism more generallyusually concluded in 1920.

At this point, my research began in earnest. Wondering if a lack of source material accounted for this neglect, I investigated further. To my delight, I discovered that the Library of Congress held a thirty-seven-reel set of microfilmed papers, representing thirty-nine boxes of manuscript material, available via interlibrary loan. I immediately ordered the first four reels, the maximum permissible quantity. I anxiously awaited their arrival, eager to see what I might find in the approximately fourteen thousand items included in the Sophonisba P. Breckinridge Papers. When my order at last arrived, I wasted no time in taking my precious reels of microfilm and my laptop computer to the little-used microfilm readers located in the basement of the University of Montana's Mansfield Library. I was not disappointed. Indeed, I soon realized that Breckinridge's papers were a treasure trove of information about women's activism in modern America.

Breckinridge was involved in virtually every reform of the Progressive and New Deal eras. Her early correspondence documented all the women's activism I had been teaching about in my U.S. women's history classes for the preceding fifteen years. As I read further, into the 1920s and 1930s, I found that Breckinridge was involved in still other reform movements that were new to me. In order to keep track of her many activities, I created a timeline on sheets of butcher paper affixed to my study wall. To organize copies of her voluminous correspondence, reams of memoranda, and draft publications, I began a growing collection of three-ring binders, organized by date and topic. To find space for all the material I was collecting, I had to build additional bookcases and reorganize my study. Soon, I had an entire room dedicated to Breckinridge.