Also by JANE MERRILL

Sex and the Scientist: The Indecent Life of Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (17531814)

(McFarland, 2018)

BY JANE MERRILL AND JOHN ENDICOTT

Aaron Burr in Exile: A Pariah in Paris, 18101811

(McFarland, 2016)

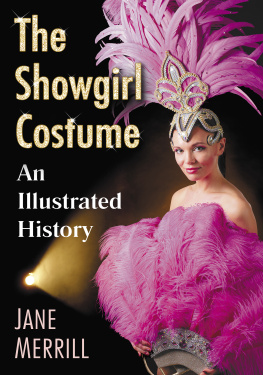

The Showgirl Costume

An Illustrated History

JANE MERRILL

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Unless otherwise indicated,

illustrations are from the authors collection.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3433-3

2019 Jane Merrill. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover photograph 2019 iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Emma, whose study of New York laws

regulating the burlesque seeded my interest in showgirl history,

and Burton, her twin, our knight in shining armor.

Its been said a woman dresses for other women because if she dressed for men she would not dress at all. Certainly when it comes to the glamorous costumes of the showgirl extravaganzas, the truth is more nuanced. Men and women alike were inspired by beautiful female bodies adorned like silvery angels. What could be a better backdrop to raise the mind above the reality of gambling tables and slot machines?

It is easy for staged nudity to look awkward. Instead, thanks to sparkling costumes and stately choreography, the shows dazzled, projected magical qualities. The audiences responded to the harmonious colors and movement and assemblage of bodies on display. The tradition itself is artful and ingenious, the revues often original, if long, andwhat was it that people said after going to the Lido in Paris?tasteful.

Those showgirls were beautiful performers. Their extinction is hard to believe.

GAY TALESE

Introduction

Sex is one of the nine reasons for reincarnation. The other eight are unimportant.Henry Miller

Finding the Terms

When Sally Bowles belted out Life is a cabaret, old chum, she knew what cabaret meant because she was in one. Showgirls have known that they are performing as sexual objectslightly clad showpieces of an aesthetic based in rhinestones, sequins, and feathers. And yet the nomenclature about them has been vague. First of all, the words surrounding the productions where the showgirl costume icon took shape are themselves diaphanous.

The word cabaret comes from a French Picard (before that, Dutch) word camberete, meaning small room. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the cabaret was in the 1600s a wooden dwelling, shed, or any joint for gaming and drinking. Samuel Pepys in his diary of September 23, 1662, noted that in most Cabaretts in France they have writ upon the walls Dieu te regard, and Dryden in Marriage la Mode (1662) mentioned a song sung, two or three years ago in Cabarets. In contemporary Qubecois, a tray in an eating establishment or at home used for carrying glasses, etc., is a cabaret.

In English, cabaret has a foreign twang. Nicolas Thibouts Prires et Instructions Chrtiennes (1737) decried cabarets as places to ruin ones health, as frequenting them led to gambling and intoxication. Henri de Saint-Simon in his memoir used the connotation to define a side table on which to put alcohol, coffee or tea for self-service. The idea of a gathering place for men of letters and artists and where parodies were presented began with Le Chat Noir, a man cave in Montmartre opened by the charismatic Rodolphe Salis in 1881.

The center of cabarets was Berlin during the Weimar era, until, writes theater historian Laurence Senelick, Within a few years of Hitlers rise to power in 1933, the Nazis effectively suppressed all hints of cabaret subculture in Germany. The European cabaret was a business but with the atmosphere of a club. The artists, poets and writers in Paris gravitated to the cabarets. The habitus created posters and published minor literary genres that advertised their chic by mocking the status quo. They hung their work on the walls of where they drank. In keeping with the fact that patrons cast themselves as outsiders, cabaret continued to have a non-native appeal. A Persian or Arabic origin has thus also been suggested.

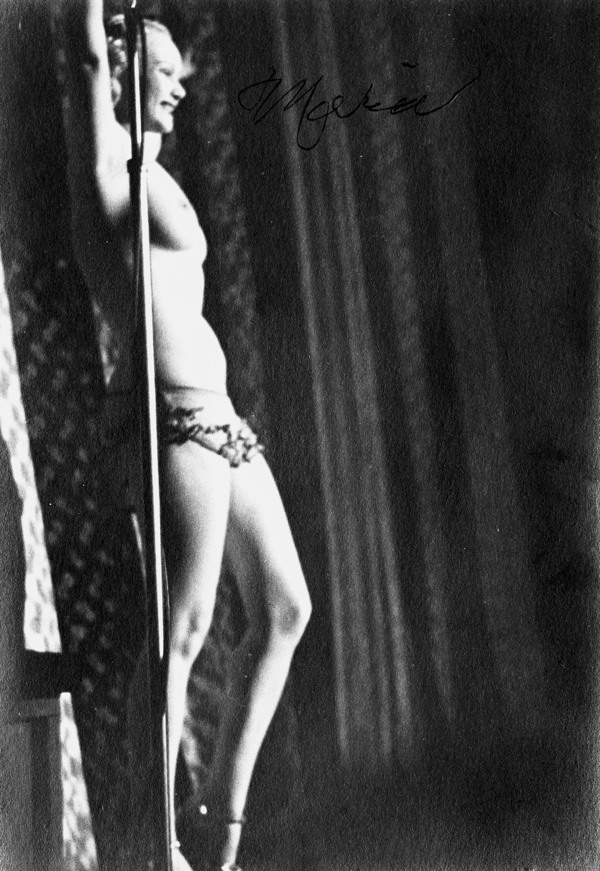

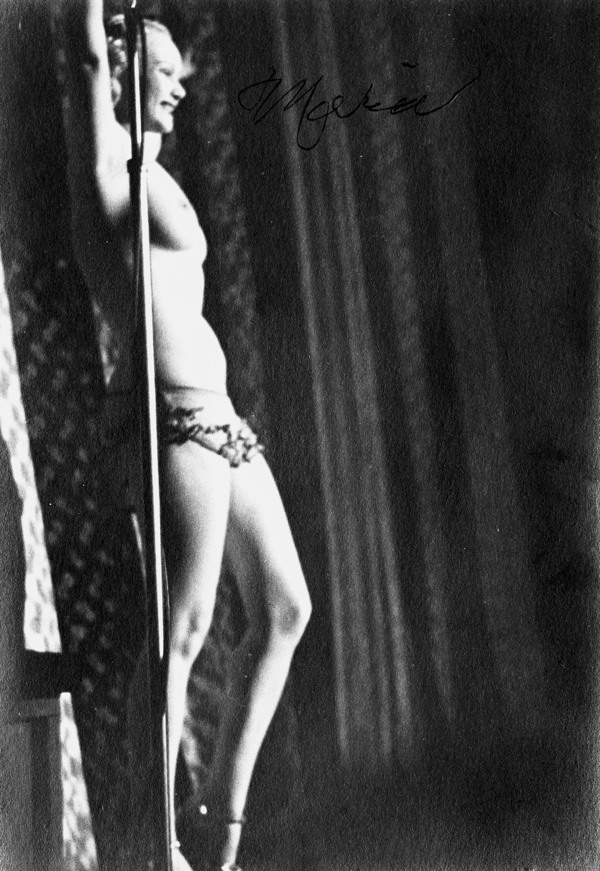

Photograph from a 1920s Paris show.

Once the stage lights went on in Paris, variety shows with dancing girls, and later professional dancers, semi-nude, became a popular indoor spectacle, eclipsing the traditional cafs-concerts. Most of the venues of this sort were known by the English term music-hall, a rubric imported from London, usually hyphenated. Meanwhile the word cabaret passed into many languages for drinking establishments with entertainment and was often retained as evocation. Further complicating the lexis, music-halls also called themselves theaters. As for the floor show that became the distinguishing characteristic of the music-hall, it began on the floor but moved to the stage. The context of the showgirl, the music-hall, stood at the top of the entertainment pyramid in the fin de sicle and the Jazz Era, yet the English word stuck. In the postWorld War II era, the gaudy frivolities, influenced by the influx of English-speaking tourists, also were referred to as botes de nuit, or nightclubs.

The word nightclub may conjure up a palm tree dcor and Miami or Havana but it appeared early in the OED with an 1871 reference from Appletons Journal: For billiards, and the best night-club in London, Pratts. Thus in London at the turn of the century the nightclub was distinct from both cabaret and music-hall (the first was opened by Charles Morton in 1952), and not yet home to showgirls. It was after Prohibition was repealed in the U.S. in 1933 that big fancy nightclubs with showgirls, and supper clubs with their little sisters, the cigarette girls, proliferated. You were, Frank Sinatra said, a show business nobody until you did three shows a night at the Copacabana, and at big nightclubs like this one, showgirl numbers provided titillation.

A quintessential spot for showgirls in the U.S. was for a long time New York City. Writes Broadway theater historian John Kenrick, In the United States, cabaret developed along more glamorous and less intellectually ambitious lines. When a 1913 ordinance forced Manhattans cabarets to close by 2:00 a.m., members-only clubs sprang up and stayed open for dancing till all hoursthe first nightclubs. Soon anyone looking for striptease and line dancers would check out the cabarets.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, no stranger to nightclubs, with wife Zelda, has a famous cabaret star at the next table in This Side of Paradise (1920), and an English newspaper in 1923 broadcast a big jazzy show at the Hotel Metropole in London as a super cabaret.

Harold B. Segel makes a sensible distinction between cabarets and nightclubs. The nightclub conjures up a physically large venue whereas the cabaret is small and intimate, and the nightclub tends to offer gaudier entertainment in the tradition of the revueraised stage, orchestra, troupe of dancers, and singers and a standup comedian or two. The contemporary cabaret, notes Segel, will have certain of these features but in scaled down form; it is, in effect, a miniature nightclub.

Next page