Page List

Page List

Guide

EDITED BY

Larry Lytle

AND

Michael Moynihan

INTRODUCTION BY

Michael Moynihan

ESSAYS BY

Larry Lytle, William Mortensen

AND

A. D. Coleman

FERAL HOUSE

2014

CONTENTS

MICHAEL MOYNIHAN

LARRY LYTLE

WILLIAM MORTENSEN AND GEORGE DUNHAM

LARRY LYTLE

A. D. COLEMAN

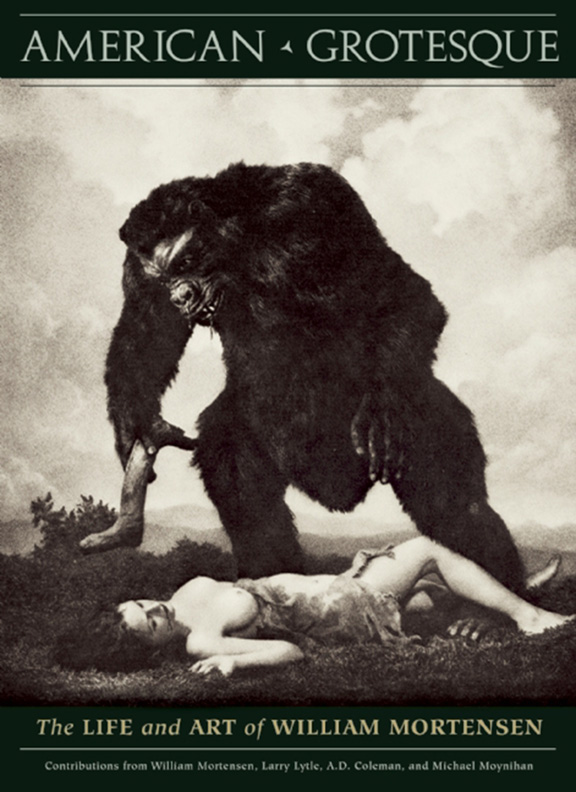

Tantric Sorcerer

Silver gelatin print, Abrasion-Tone Process, Metal-Chrome

George Dunham model; N.D., circa 1932

(CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY)

Renaissance grotesque decoration,

Palazzo Assessorile of Cles, Trento, Italy.

Photograph by Resettimapiu.

MICHAEL MOYNIHAN

N

o matter how hard we may wish to avert seeing it, the grotesque lurks nearby to impress our gaze, distress our state of mind and scratch away at sterile surfaces to reveal the

horror that lies beneath.

It requires honesty to acknowledge that the grotesque invades each of our lives, and that the best way to handle it is to come to grips with its essential power. Perhaps we should simply admit that the grotesque intoxicates both attracting and repelling all at once.

The task of interpreting the grotesque usually falls to artists: writers, singers, painters, printmakers and, in increasing prominence over the last hundred years, photographers and filmmakers. It should come as no surprise that the word grotesque has its origins in reference to visual art. In the late fifteenth century, on the Esquiline Hill of Rome, the remnants of a magnificent building complex were accidentally discovered when a bit of the ground above it gave way. The ornamented, cave-like space was called a grotta or grotto, and the fanciful depictions of hybrid human, animal and vegetal forms that decorated its walls and ceilings were labeled grottesca, or grottoesque, by the Renaissance Italians. These rooms were the vestiges of the Domus Aurea, Emperor Neros Golden House, a pleasure palace that had been condemned and buried with embarrassment by the emperors who succeeded him. It is fitting that the grotesque was first

glimpsed in a sunken chamber lost to sunlight, and originally built by a suicidal tyrant famed for his excess and cruelty.

Renaissance painters soon began imitating the ancient art form they spied by torchlight on those underground walls, and a genre was reborn. The parameters of what was labeled grotesque slowly widened, and over time they darkened too: the word came to encompass all manner of disturbing, distorted and diabolical images, as it still does.

Many of the greatest European painters have incorporated the grotesque in their work: Bosch, Drer, Breughel, Goya and countless other artists. Major art movementsRomanticism, Symbolism, Expressionism and Surrealismregularly explored both real and unreal aspects of the grotesque as well. Thus grotesque visions have multiplied over the centuries, and museums now abound with them.

Although America can claim a titan of grotesque literary expression in Edgar Allen Poe, American visual artists by and large avoided similar themes until well after the Second World War. There were exceptions to this rule, however, and they largely emerge from the magical medium of film: motion pictures and still photography.

Tod Browning (18801962) made dozens of films utilizing grotesque themes, and took the latter to a high art in Freaks (1932). Less well known are the photographers. Francis Bruguire (18791945) created an array of expressionist and multiple-exposure experiments, many with deliberately perverse qualities. The work of Lejaren Hiller (b. John Hiller; 18801969) centered on elaborately staged tableau

1 A remarkable survey of grotesque themes in European art and literature over the

last two millennia is Umberto Eco, ed., On Ugliness, trans. Alaistair McEwen

(New York: Rizzoli, 2007).

2 Larry Lytle deserves the credit for situating the following figuresBruguire,

Hiller and, most importantly, William Mortensenas the first American

visual artists to consistently work in the realm of the grotesque.

ABOVE LEFT: Hieronymus Bosch,

Christ Carrying the Cross,

oil on wooden panel, ca. 1515.

ABOVE RIGHT: Albrecht Drer,

Cain Kills Abel, woodcut, 1511.

scenessome of which, such as his commissioned series on Surgery through the Ages , deftly combine frightful and erotic elements.

The most dedicated early twentieth-century American visual pioneer of the grotesque is undoubtedly William Mortensen. During his early career in Hollywood in the 1920s and 30s, Mortensen began a systematic exploration of deliberately grotesque themes and visions that remains unparalleled. While Mortensen produced a body of work that ranges from professional portraits (he shot many of the great cinema stars of his day) and sundry character studies to sensuous nudes, the grotesque became a defining element of his most compelling work and therefore serves as the thematic cornerstone for this book.

American Grotesque consists of five distinct sections. The journey begins with Larry Lytles biographical essay, exploring every period of Mortensens photographic development as well as the various creative streams and controversies in which he immersed himself. This is followed by Mortensens most important manifesto, Venus and Vulcan: An Essay on Creative Pictorialism, in which he lays out his personal philosophy and approach to the creation of photographic art. In the next section, A Glossary of Mortensens Methods, Larry Lytle provides an overview of the various technical processes that Mortensen invented or improved, mastered and subsequently promoted and taught. The intricate and time-consuming nature of these techniques reveals the level of craftsmanship and obsessive energy that Mortensen invested in rendering his artistic visions.

3 More grotesque than any of his actual photographs is Hillers notorious advice

regarding artistic techniques: If a man wants to strangle his wife and throw

her in the kitchen sink, let him do it any way he wants to. If hes doing it

awkwardly, or not the way Id do it, all rightits a good job so long as he

gets her into the sink, completely strangled. See Barbara Green, Lejaren

Hiller, The Camera, vol. 65, February 1943, 2024; here at 24.

ABOVE LEFT: Pieter Breughel the Elder,

The Fall of the Rebel Angels (detail),

oil on wood, 1562.

ABOVE RIGHT: Francisco Goya, Buen

viaje (Bon Voyage; Capricho no. 64),

aquatint, 17971798.

A Mortensen Gallery of Grotesques forms the main visual section of the book and comprises more than 100 photographs, many of which have never been published before. The gallery is divided into five thematic divisionsPropaganda, The Occult, Character Portraits, Nudes and Beautiful Girls into Croneswhich offer an organizational structure and hint at the breadth of Mortensens outlook both within and beyond the concept of the grotesque.

The pictures collected under the rubric of The Occult are of particular interest, for they represent our attempt to reassemble the images Mortensen created for his planned Pictorial History of Witchcraft and Demonology. As he once explained:

A very fruitful field for grotesque art is afforded by the manifestations of witchcraft and demonology. Fear, secrecy, and converse with evil powers, were characteristic elements of this mysterious cult which is as old as man. These elements are of the very substance of the grotesque... but little has been done with it by photographers.