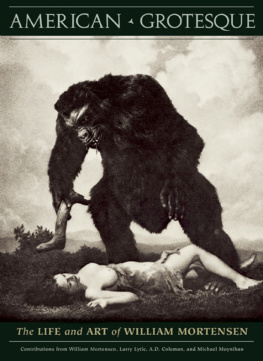

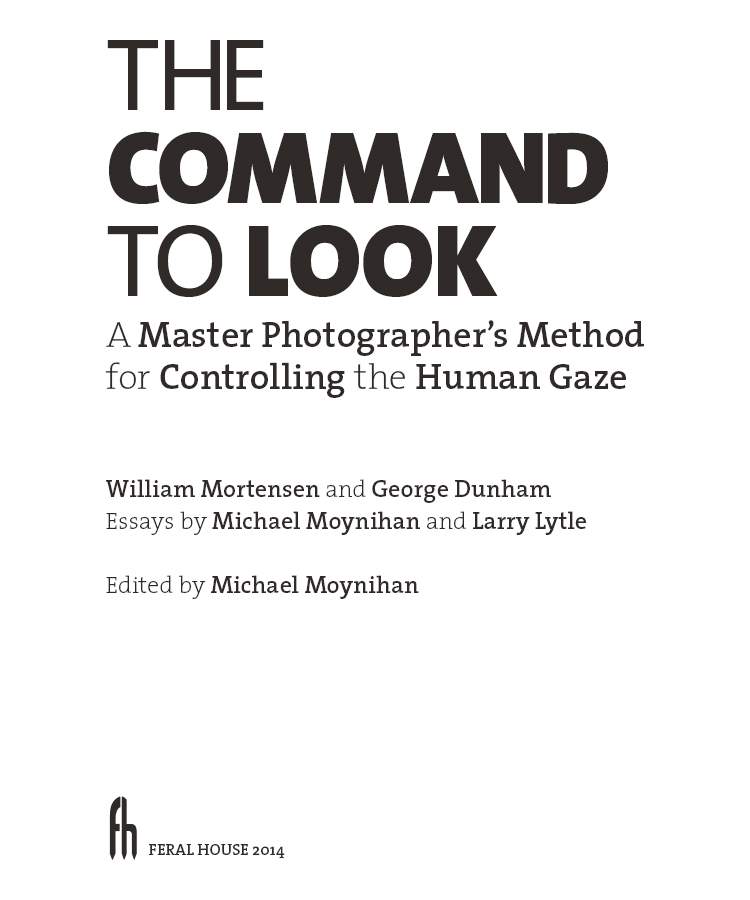

The Command To Look 1937, 2014 by William Mortensen, George Dunham, and Feral House

Infernal Impact 2014 by Michael Moynihan

The Story of The Command to Look 2014 by Larry Lytle

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Jacob Covey

Feral House

1240 W. Sims Way #124

Port Townsend, WA 98368

FERALHOUSE.COM

The text of The Command to Look for this Feral House edition is based on the fourth printing from July 1945. Only minor changes have been made with regard to orthography and punctuation style.

Thanks to Blanche Barton, Joshua Buckley, Peter Gilmore, and Monica Rochester for assistance with various aspects of this new edition.

In the essays by Larry Lytle and Michael Moynihan, footnote references for text quotations from The Command to Look are keyed to the present edition.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

by Larry Lytle

by William Mortensen and George Dunham

by Michael Moynihan

LARRY LYTLE

ALTHOUGH PHOTOGRAPHY POSSESSES a visual language unto itself, printed books that unite photographic images with meaningful text have played an important role in the development of the art form. There are even a few twentieth-century photographers who gained a degree of recognition as literary figures, such as Edward Weston (18861958) with his Day Books and Ansel Adams (19021984) with his technical books on the craft. In explaining their respective approaches and philosophies, they expanded not only our appreciation of the iconic images they created, but also our understanding of the vocabulary and meaning of the photographic medium itself.

At different times in their careers, both men collaborated with female writers who further developed their ideas. Westons model Charis Wilson (19142009) became his muse and later his wife, and wrote the text for his California and the West. The photography critic and conservationist Nancy Newhall (19081974) collaborated with Adams on This Is the American Earth. These two books are rightly considered classics.

William Mortensen (18971965) is another photographer whose images and writings about the medium are equally as important as those by the aforementioned figures, although his work was unjustly ignored and overlooked after it fell out of favor in the mid-twentieth century. Like Weston and Adams, Mortensen collaborated on all of his texts with someone whom he felt could better express his techniques and theories. This was George Dunham.artists spearheading the ascendant genre of straight or purist photography. As the purist ideal came to dominate the field, other approaches like Mortensens creative pictorialism were relegated to obscurity by the art establishment.

In the 1980s the tide began to slowly turn in Mortensens favor, and since then a growing revival of interest in his work has been underway. He has been included in recent histories of photography and museum exhibitions, and information about him and his images increasingly appears on the Web. Some of this newfound appeal is a result of Mortensens distinctive methods for making his pictures. To the untutored eye, many of these images could be mistaken for digital manipulations, even though they were created well before the invention of the home computer. Now that the advocates of straight photography have lost their control over the history of the medium itself, enthusiasts are rediscovering Mortensen as an unsung innovator from photographys past.

Even though Mortensens images have begun to make a comeback, his attendant writings have not yet been fully recognized for their many insights. This is partly due to the scarcity and fragility of the old magazines that carried his articles, and the same is true of his books, which often fetch high prices from rare book dealers and auction sites.

To read Mortensen is to understand his visual work. He openly courted controversy with his devilish ideas, and he used books and articles as a platform to disseminate the Mortensen Methods. He accomplished this through his fine descriptive abilities and the witty rhetorical style of his coauthor George Dunham. Mortensen drew from areas that ranged widelyencompassing literature, art history and psychologyand as a result his explanations are far more fascinating than is the case with other photographers whose writings simply serve to document their own particular technique.

To appreciate Mortensens proper place in the history of photography, it is necessary to explore the underlying ideas that inspired his preternatural imagery. Mortensen laid out the basics and in his first four books on methodsProjection Control (1934), Pictorial Lighting (1935), Monsters & Madonnas (1936) and The Model (1937). But it is his fifth and most compact book, The Command to Look (1937), with its innovative application of psychology to photography, that serves as the real master key for unlocking the secrets of William Mortensens singular vision.

BEFORE WE CONSIDER the theories that William Mortensen advanced in The Command to Look, it is important to look at the development of the book itself, and why Mortensen felt compelled to write it. Clues to this genesis can be found embedded in a series of letters that Mortensen exchanged with Richard Simon of the New York publishing house Simon & Schuster.

In January of 1936, Richard Simon contacted Mortensen about writing a comprehensive technical photography manual, fully illustrated, and between three hundred and seven hundred pages in length..

Over the next several months, the two men exchanged letters in which they discussed the proposed books contents and hammered out details concerning royalties, delivery date for the manuscript, and so on. Mortensen began working on the book in the late summer of 1936. By that October, however, he sent Simon a telling letter saying that hed been barking up the wrong tree. There is definite need for such a book as I have describedbut fear that it will have to be written by someone of different qualifications than myself.

Mortensen felt that the result would be little more than another version of Walls Dictionary of Photography, albeit from his personal perspective. Furthermore, he explained:

The truth is I am not constitutionally fitted to write an academically sound book. I am radical, personal and prejudicedand when I see a head I am liable to hit it. I have a system, and am a fanatic advocate of it. Photographers of the older school assure me that my system is fantastic, unscientific and subversive. My unscientific justification is that it works, and that nearly five hundred pupils of mine have found the same. The thing that has distinguished my writings from many much more learned and sound books has been (as I deduce from reviews and fan letters) their personal quality and their irreverent dealing with cherished and hoary bugaboos of the profession. The paradox of the matter is that my heresies seem to be more firmly grounded in artistic tradition than are the cautious conventions of old-line photographers.

Next page