To

Kate Kingsley Skattebol

and

Charles Latimer

(19372002)

Contents

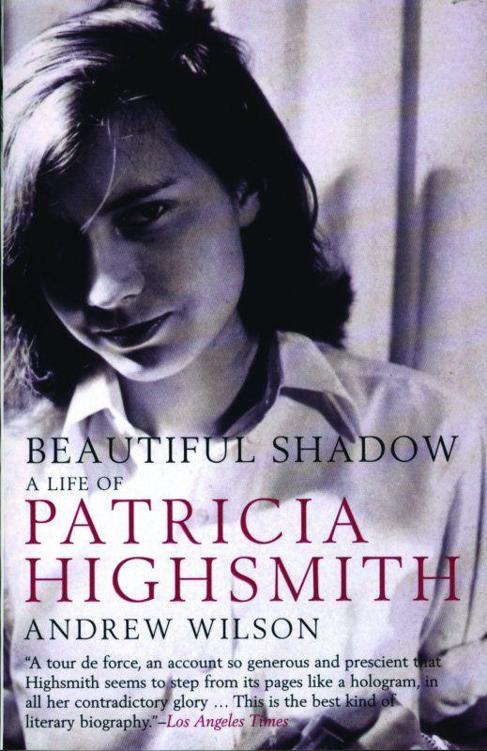

The individual has manifold shadows, all of which resemble him, and from time to time have equal claim to be the man himself.

Kierkegaard quoted in Highsmiths 1949 journal

When Patricia Highsmith looked up at the luminous face of the clock at the entrance to Pennsylvania station, New York, she would have seen two stone-sculpted maidens flanking the extravagant timepiece. One figure stared out across Manhattan to signify day; the other, with eyes closed, symbolised night an appropriate double image for Highsmith herself, a writer fascinated by the concept of split identity. On that particular day 30 June 1950 the twenty-nine-year-old novelist was in pursuit of her antithesis: a blonde, married woman she had cast as a mannequin in a romantic drama of her own creation. She was going in search of the woman who had, unwittingly, inspired her lesbian novel, The Price of Salt .

In December 1948 a year and a half before Highsmith found herself walking through Pennsylvania station she was working, temporarily, in the toy department of Bloomingdales when into the store walked an elegant woman wearing a mink coat. That initial encounter lasted no longer than a few minutes, yet its effect on Highsmith was dramatic. After serving the woman, who bought a doll for one of her daughters, leaving her delivery details, Highsmith later confessed to feeling odd and swimmy in the head, near to fainting, yet at the same time uplifted, as if I had seen a vision.

The Bloomingdales woman had done nothing more than buy a doll from a shop assistant in a department store, yet Highsmith had infused the encounter with greater significance. She could not forget the blonde woman and on that day in the summer of 1950 she walked through Pennsylvania station with the intention of catching a train to the womans home in New Jersey. She was going to seek her out, to spy on her.

Highsmith recorded the incident in almost photographic detail in her diary. As she stepped on to the train bound for Ridgewood, she felt as guilty as a murderer in a novel and on arrival at the suburban station she had to drink two rye whiskeys in order to steady her nerves. At Ridgewood station, she climbed on board a 92 bus, but after a few minutes, worrying that she was going the wrong way, she asked the driver whether he had already passed by Murray Avenue, the womans home. Murray Avenue? said the other passengers, as they all started to shout the correct directions at her. Blushing, she stepped down from the bus and started walking through the neatly planned, suburban streets towards the womans house.

When Highsmith reached North Murray Avenue, a small lane backing onto woodland, she felt so conspicuous and overwhelmed by guilt she decided to turn back. But then an aquamarine car eased its way out of a driveway and headed towards her. Inside was a woman with blonde hair, wearing a pale-blue dress and dark glasses. It was her.

Already fascinated by the intertwined motives of love and hate, Highsmith wrote in her journal: For the curious thing yesterday, I felt quite close to murder too, as I went to see the woman who almost made me love her when I saw her a moment in December, 1948. Murder is a kind of making love, a kind of possessing. (Is it not, too, a way of gaining complete and passionate attention, for a moment, from the object of ones attentions?) To arrest her suddenly, my hands upon her throat (which I should really like to kiss) as if I took a photograph, to make her in an instant cool and rigid as a statue.

On her return to New York she noticed that strangers eyed her with suspicion, as if they could see the traces of her guilt smeared across her face. Although the two women did not meet that day in Ridgewood, within six months Highsmith felt driven to try and see her again. In January 1951, as she was writing The Price of Salt , which details a love affair between two women Therese, a shopgirl in a toy department and Carol, a customer, who is married with a child Highsmith made another trip out to New Jersey. This time she noted how the womans house, with its black turrets and greyish towers, looked like something out of a fairy tale. She closed her eyes and imprinted the image in her memory, before watching the womans children at play, observing how little they resembled their mother. Yes, I am delighted my Beatrice lives in such a house, she wrote in her diary.

Highsmith projected a complex array of emotions onto the woman, so she became both the model for Carol in The Price of Salt and an externalised embodiment of past lovers, an incarnation of her drives, desires and frustrations. Highsmith could be called a balladeer of stalking, wrote Susannah Clapp in The New Yorker . The fixation of one person on another oscillating between attraction and antagonism figures prominently in almost every Highsmith tale. Specifically, she used the women in her life a quite dizzying parade of lovers as muses, drawing upon her ambiguous responses to them and reworking these feelings into fiction.

Like many a romantic, she was, at times, promiscuous, but her bedhopping was an indicator, rather than a confutation, of her endless search for the ideal. To paraphrase Djuna Barnes novel Nightwood a book given to her by one of the women she worshipped in Highsmiths heart lay the fossils of each of the women she loved, intaglios of their identities. All my life work will be an undedicated monument to a woman, she wrote in her diary.

Publicly, however, Highsmith was reluctant to talk about her writing, precisely because she knew its source was often so very close to home. She was the least forthcoming of authors, and hated talking about her work, says Craig Brown, who interviewed her on a number of occasions.

It wasnt only journalists who had a problem getting close to her. Daniel Keel, her literary executor and president of Diogenes Verlag, the Zurich-based publishing company, says it took Highsmith twenty years before she trusted him enough to share her thoughts and feelings. Before that it was simply yes or no, he says. There were great holes in the conversation.

Barbara Roett, the partner of the late Barbara Ker-Seymer, remembers how Highsmith would tense up when touched. She wasnt a sensual person at all when you embraced her, it was like holding a board. I always remember that she was quite shocked when I once said, I must go and lie in the bath. Shed never actually laid down in a bath rather, she would sit bolt upright in it. I said, Pat, how can you? How could you sit upright in a bath? She replied, I would never lie down. I just had the feeling somehow she was not comfortable in her own body.

Vivien De Bernardi, a friend who lived near Highsmith in Switzerland, and one of her executors, believes the writer had a problem with intimacy. She may have had numerous sexual partners but she did not have that many people with whom she was genuinely intimate. Her relationships never lasted very long.

She was sincere and direct those are two key words that describe Pat and she did not have a drop of dishonesty in her. Yet, I didnt like the ranting and raving, the nastiness, the hatred which would overflow. She would get on a subject and she would not give it up. She was like a dog gnawing on a bone. There were some subjects that, when she talked about them, I considered her to be a raving maniac. Her really true friends loved her in spite of some of her behaviour.

It was obvious that this tremendous emotional reaction had nothing to do with reality. It was something internal and it was agonising for her. The nastiness had much more to do with her with her inner state, her depression, her anger, and her self-hatred than anything external.