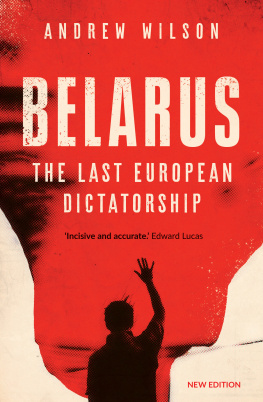

Andrew Wilson is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, and Professor in Ukrainian Studies at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College, London. He has published widely on the politics of Eastern Europe, including Ukraines Orange Revolution and Virtual Politics: Faking Democracy in the Post-Soviet World, both published by Yale University Press and joint winners of the Alexander Nove Prize in 2007. More recently he has published Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship (2011) and Ukraine Crisis: What the West Needs to Know (2014), again both with Yale University Press. His recent publications at the European Council on Foreign Relations (www.ecfr.eu) are Protecting the European Choice and What does Ukraine think?

Copyright 2000, 2002, 2009, 2015 by Andrew Wilson

First published in 2000

Second edition published in 2002

Third edition published in 2009

Fourth edition published in 2015

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. office

Europe office

Set in Sabon by Fakenham Photosetting, Norfolk and IDS (UK) Data Connection Printed in Great Britain by Hobbs the Printers, Totton, Hampshire

Library of Congress Catalog Control Number 2009934897

ISBN: 978-0-300-21725-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Ella and Alfie

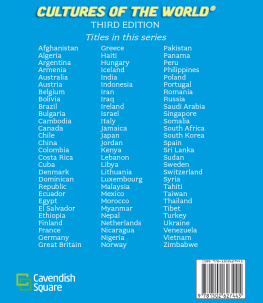

Contents

Illustrations

Illustrations in the text

Andrei Bogoliubskii taking the Vyshhorod/Vladimir Icon (Jaroslaw Pelenski, The Contest for the Legacy of Kievan Rus, 1998)

The assassination of Bogoliubskii, 1175 (Pelenski, ibid.)

Lev Sylenko, Guest from the Tomb of our Forefathers (Hist z Khramu Predkiv, 1996)

Two Sovereigns, 1654 and Two Sovereignties, 1990 (Rukh-press cartoon, 1991)

Ukrainian nationalist cartoons (Samostiina Ukrana, 1991, Post-postup, 19915)

Ukrainian leftist cartoons (Tovarysh, Komunist, 19949)

Kuchma attacked for abandoning the programme on which he was elected (Tovarysh, 1998)

The Tree of the Christian Church (poster from Pochav monastery, 1998)

The Ukrainian way of inflation (Post-postup, 1992)

Yurii Lypas map of Ukrainian and Russian energy sources (Rozpodil Rossi, 1941)

The development of Ukrainian national territory, 12001910 (adapted from Volodymyr Kubiiovych, Historischer Atlas der Ukraine, 1941)

Rudolf Kjelln, The Nationality Map of Europe (adapted from Die politischen Probleme des Weltkrieges, 1916)

Zbigniew Brzezinski, A Geostrategy for Eurasia, 1997 (Foreign Affairs, September/October 1997)

Aleksandr Dugins map of Ukraine (Osnovy geopolitiki. Geopoliticheskoe budushchee Rossii, 1997)

Ukraine shown as a set of sub-ethnoses of the Great Russian people (Russkii Geopoliticheskii Sbornik, 1997)

Alexei Mitfrofanov, The West and South of European Russia (adapted from Shagi novoi geopolitiki, 1997)

Halford Mackinders plan for a new Europe, 191920 (Geographical Journal, 1976)

Yurii Lypas map of Russia, 1941 (Rozpodil Rossi, 1941)

Maps

Rus in the Twelfth Century

The Seventeenth Century: Ruthenia, Poland, Muscovy, Zaporozhia

Ukraine in the Nineteenth Century

Ukraine, 191720

Ukraine Between the Wars

Independent Ukraine after 1991

Black and white plates between pages 110 and 111

Pyrohoshcha church of the Virgin, Kiev (authors photo)

St Sofiias, Novgorod

Annunciation of Ustiug (State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow)

Virgin Oranta (State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow)

Statue of Ivan Pidkova, Lviv (authors photo)

Cathedral of the Assumption, Pechersk, Kiev (computer reconstruction, Welcome to Ukraine, 1997)

St Nicholas church, Kiev (computer reconstruction, ibid.)

Socialist Realist sculpture, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue to the Eternal Unity of the Ukrainian and Russian peoples, Kiev, 1954 (authors photo)

Statue of Holokhvastov, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue of Panikovskyi, Kiev (authors photo)

Memorial to the Great Famine, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue of Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue of the Archangel Michael, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue of Taras Shevchenko, Lviv (authors photo)

Cartoon mocking Ukrainian materialism (Rukh-press, 1991)

Colour plates between pages 174 and 175

Virgin of Vyshhorod/Vladimir (State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow)

Angel with the Golden Hair (State Russian Museum, St Petersburg)

John Martin, The Last Judgement, 1853 (Tate Britain, London)

Virgin Oranta, St Sofiias, Kiev

Ilia Repin, Zaporozhian Cossacks Writing a Mocking Letter to the Turkish Sultan, 1891 (State Russian Museum, St Petersburg)

Mykola Ivasiuk, Khmelnytskyis Entry into Kiev, 1649, 1912 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

SS Anastasia and Juliana, mid-eighteenth century (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Holy Protectress or Intercession of the Mother of God, late seventeenth century (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Viktor Vasnetsov, Baptism of the Kievites, 1895 (St Volodymyr Cathedral, Kiev)

Nicholas Roerich, designs for The Rite of Spring (Jacqueline Decter, The Life and Times of Nicholas Roerich, 1989)

Oleksandr Murashko, Annunciation, 19078 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Vsevolod Maksymovych, The Two, 1913 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Anatolii Petrytskyi, Young Woman, 1921 (Museum of Theatre and Cinema, Kiev)

Mariia Syniakova, Bomb, 1916 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

David Burliuk, Carousel, 1921 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Vasyl Yermelov, A, 1928 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Ivan Paschchyn, The Smiths, 1930 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Kasimir Malevich, The Running Man, 19334 (Muse National dArt Moderne, Paris)

Mykhailo Khmelko, Triumph of the Conquering People, 1949 (Tretiakov, Moscow)

Mykhailo Khmelko, Eternal Unity, 1954 (authors photo of version in L-Art Gallery, Kiev)

War posters (Mistetstvo narodzhene zhovtnem, 1987)

Tetiana Yablonska, Bread, 1949 (State Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow)

The monastery of St Michael of the Golden Domes, Kiev (authors photo)

Statue of Yaroslav the Wise, Kiev (authors photo)

View of St Sofiias and Khmelnytskyi statue, Kiev (authors photo)

Oles Semerniia, My Town, 1982 (National Museum of Fine Art, Kiev)

Two-hryvnia note, showing Yaroslav the Wise

Preface to the Fourth Edition

Why the unexpected nation? Most obviously, the emergence of an independent Ukrainian state in 1991 came as a great surprise in the chancelleries, universities and boardrooms of the West a surprise that many are still adjusting to. There were also very real reasons why Ukraine was then considered to be an unlikely candidate as a new nation, given its pronounced patterns of ethnic, linguistic, religious and regional diversity. However, an unexpected nation is still a nation no more and no less than many others. The 2014 crisis showed that the elite of Putins Russia clearly thought otherwise (as outlined in ). To them, Ukraine simply does not exist, or Ukrainians and Russians are one nation, or its Russian-lite parts should be sub-divided from the rest. Putin could have stopped at the annexation of Crimea, but did not. He was unlikely to stop with half of the economic wastelands of the Donbas under his proxies control. His broader aim was to make the rest of Ukraine a dysfunctional state. At the time of rewriting, Ukraine was facing economic collapse, and not enough had changed politically, but on this key existential question Putin seemed to have failed. Ukraine was more united after the crisis than before.

Next page