Also by Judith L. Pearson

This book is dedicated to the men and women whose bravery, sacrifices, and vision in the little-known world of espionage turned the course of a world war

Prologue

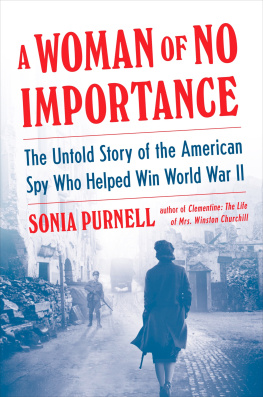

MARCH 1944

The old woman bent her gray head against the frigid wind blowing in from the English Channel as she struggled along the rocky Brittany seaboard. The French province had 750 miles of coastline, all of it inclement during the month of March. And on this particular March day in 1944, the wind seemed set on toppling her over. She was determined to stay her course, however, and shuffled on.

The old man traveling with her also struggled. He appeared less steady than she was and occasionally took her arm to regain his footing. It was obvious from his gait, even to the most casual observer, that his left leg caused him pain. To make matters worse, the wooden sabots they wore were not suitable shoes for hiking along such a rutted road.

Each carrying a battered suitcase, they struggled against the cold wind for a little more than five miles before they finally arrived at their destination: the city of Morlaix. There, the elderly couple made their way to the railroad station and purchased two second-class tickets for Paris. When the time came to depart, they sat in adjacent seats, her bulky woolen skirts taking up a great deal of room on both sides. The train ride took nearly six hours, and it was late when they arrived at the Montparnasse station in the southwestern part of the city.

Paris looked nothing like it did when the old woman had been there on a previous visit. That had been in the spring of 1940 when national spirit ran high and the tricolore flew proudly from many buildings. Then, even the spring sun had made an effort at encouragement, shining through the smoke of burning structures and exploding shells. The French army was fighting furiously to repel the powerful advancing Nazi forces. Under the leadership of seventy-two-year-old General Maxime Weygand, the French had hastily prepared defenses. The old woman had done her part for the war effort too, transporting wounded French soldiers as an ambulance driver.

The German onslaught continued, and just before the invaders dealt their sledgehammer blow on June 5, the old woman had left the city. The French line soon crumbled and by June 14, Paris was declared an open city, a request to the enemy to cease firing upon it. On the twenty-first, Hitler himself was at Compigne, 80 kilometers outside the capital and the precise spot where the Germans had been forced to surrender to the French at the close of World War I. The Fhrer had malevolently chosen the same location to dictate his harsh terms for this surrender.

It was now almost four years later. Blackout curtains kept the City of Lights in the dark. Signs of war were everywhereburned-out buildings, abandoned military vehicles, looted shops. But nowhere was the war more apparent than on the faces of the passersby the old couple encountered on the streets. Fear and mistrust, borne out of the hell of brutal control under the Nazis, was common among French citizens.

A few among them were oblivious to the condition of their beautiful city. They pranced by, dressed in furs, their pampered poodles on satin leashes. They were the collaboratorsthe kept women of the Nazi officers.

The old woman did not feel fear. Rather, the ravages of war that had destroyed the city repulsed her. The farther she and the old man trudged, the more that repulsion festered into anger and determination. She drew her shabby valise closer in an unconscious effort to guard its precious contents.

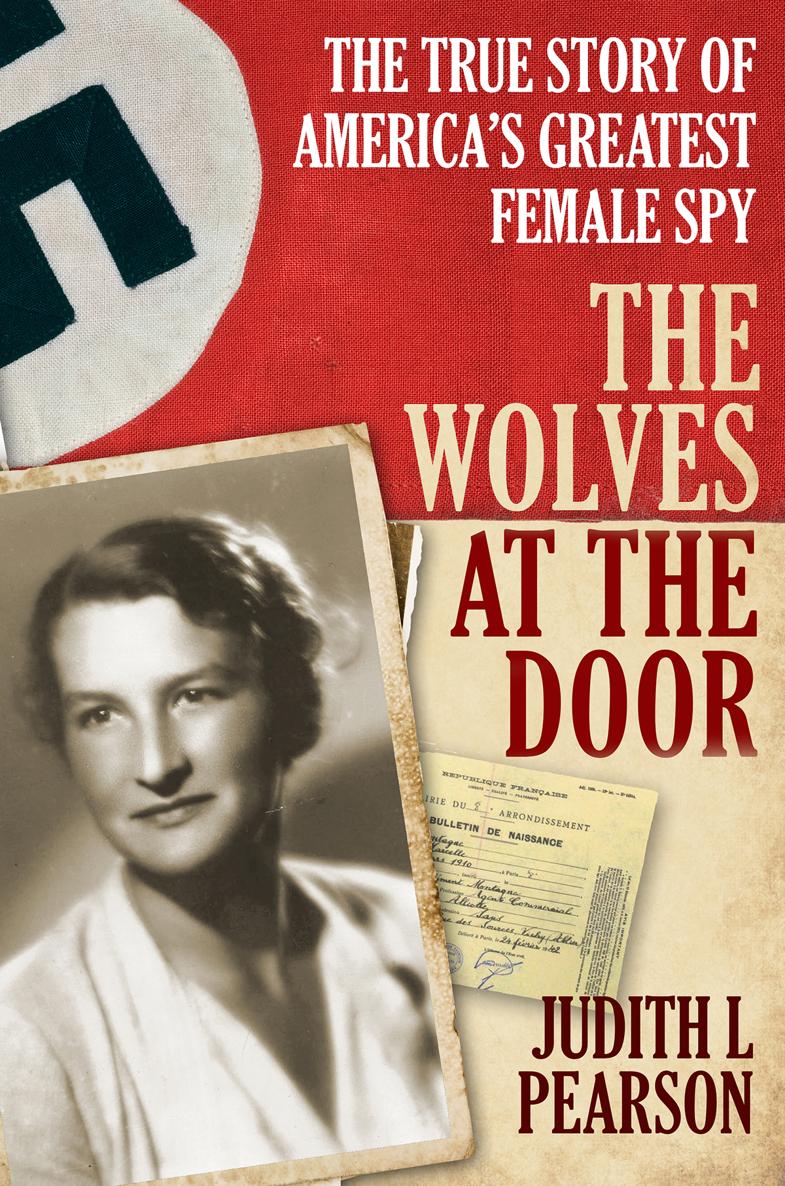

Despite their appearances, the feeble, elderly couples true identities couldnt have been further removed from their current personae. He was Henry Laussucq, code-named Aramis, a sixty-two-year-old American agent of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). She was Virginia Hall, code-named Diane, the accomplished, thirty-eight-year-old spy who had built a reputation among colleagues and enemies alike while working with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). Now also a member of the OSS, Hall was returning to France despite a price on her head and a Nazi pledge to find and destroy her. Together with other OSS agents, they were to assist the newly formed French Forces of the Interior in coordinating Resistance efforts.

The couples elaborate disguises had been created out of a necessity to camouflage Halls more recognizable features. She had dyed her soft brown hair a shade of dirty gray and pulled it into a tight bun, giving her young face a severe appearance. Then she hid it all under a frayed babushka. She disguised her slender figure under peplums and full skirts, topped with large woolen blouses and a shabby oversized sweater, to give her a look of stoutness. Her most identifiable feature, however, the limp caused by her artificial left leg, couldnt be eliminated. But it could be altered. An accomplished actress, Hall taught herself to walk with a shuffle, a gait suitable for a woman of her assumed age.

The couple spent the night at a safe house, resting and enjoying a fairly substantial meal, considering the scarcity of food in Paris. The next morning, they made their way to the Saint-Lazare train station, passing numerous Nazi soldiers who paid them little, if any, attention. What, after all, would be the purpose of harassing an impoverished, elderly French couple? Still, Halls heart skipped a beat at each encounter; a combination of trepidation, knowing the fate awaiting her should she be caught, and anticipation, knowing the damage her work would wreak on the Nazi war machine.

Their train journey southward to the city of Crozant took a little over two hours. After walking another mile to a nearby village, they located a farmhouse belonging to Eugne Lopinat. M. Lopinat was not a declared member of the growing French Resistance, but neither was he a Nazi sympathizer. The Resistance had chosen him for his reputation of being short on conversation and asked him to find the old woman lodging. He had chosen a one-room cottage he owned at the opposite end of the village from his farmhouse, a shack with no running water or electricity.

Aramis had orders to install himself in Paris and departed soon after Hall settled into her cottage. She was glad to be free of him. She thought he talked too much and was somewhat indiscreet, two qualities that could bring a quick and painful end to an OSS agent.

In exchange for rent, Hall was to work at Lopinats farmhouse cooking meals for the farmers family, taking their cows to pasture in the morning, and retrieving them each evening. It was then that Halls real work began. The suitcase she had carried since landing in Brittany contained a Type 3 Mark II transceiver. Hall used the set to transmit messages to the London OSS office, giving coordinates of large fields she had located during the day while moving Lopinats cows to and from pasture. The fields were to serve as parachute drops for agents and supplies in support of the French Resistance. The work carried high risks. Hall had to be vigilant of Nazi direction finders, instruments used to zero in on radio transmissions. She would need to relocate quickly if it became apparent that the Gestapo was moving in.