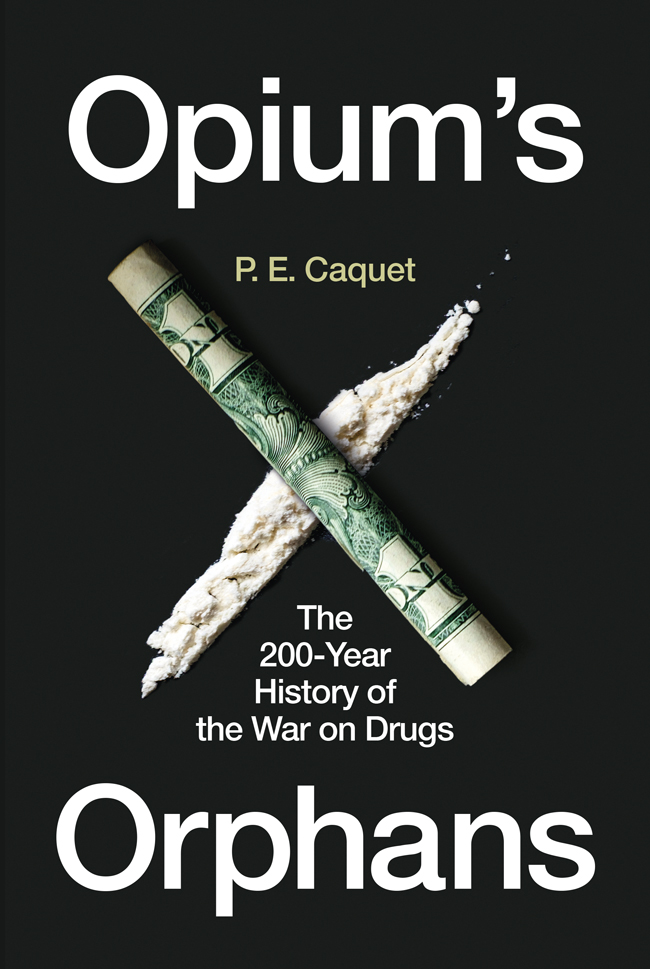

OPIUMS ORPHANS

OPIUMS

THE

200-YEAR

HISTORY OF

THE WAR ON DRUGS

ORPHANS

P. E. CAQUET

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2022

Copyright P. E. Caquet 2022

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789145595

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON WEIGHTS AND CURRENCIES

This book makes frequent use of statistics. These range over a long time period and a broad geography, inevitably involving differing measures of weight and different currencies. Where applicable, the author has converted these into metric-system measures, especially kilograms and metric tons. These are the yardsticks the United Nations use, the source for many of the statistics deployed here. The main currency of reference, likewise, is the U.S. dollar, and for silver and gold the chosen unit remains the ounce. In places, for reasons of readability, original measurement units have been retained (for example the opium chest), especially the main units used by the Chinese or British in the nineteenth century. Where this is the case, their conversion value is offered in parentheses. In the days of the gold standard and metallic currencies, dollars, whether American, Spanish or Mexican, or Indochinese piasters, were often very close in value.

PROLOGUE

I n the leafy town of Taiyu, Shanxi, an inland Chinese province southwest of Beijing, the district magistrate Chen Lihe had a stele put up for public display. The date was 1817 and, four years earlier, the emperor had issued a raft of regulations against opium, including severe punishments for handling, selling or consuming it. The stele read:

Opium is produced beyond the seas, but its poison flows into China. Those who buy it and consume it break their families, harm their own lives, and violate the law. Treachery, licentiousness, robbery, and brigandage all arise from it. Both the young and vigorous and the old and weak die from it. Wealthy and luxurious houses are impoverished by it. Brave and bright sons and younger brothers are made stupid and unfilial by it. People who dwell in peace in their houses well stocked with delicacies feel the heavy blows of the bamboo and the weight of the cangue because of it; they also suffer strangulation, exile, and banishment at the hands of the law because of it.

As for its injurious effect on custom, opium destroys the five natural relationships, and its harmful effect on individual character is even more unspeakable... To eradicate a great scourge, its source must first be cleansed. If the district were without traffickers, from where would my people buy opium? If there were no traffickers outside its boundaries, from where would my district buy opium?... Henceforward,

By proclaiming the severest penalties against everything to do with opium, including its possession, the Chinese imperial court had in 1813 launched an all-out campaign against the drug. It sent out orders for enforcement throughout the country, including to provinces, such as Shanxi, that lay far from the coasts through which opium flowed. The stele reveals motivations that ring surprisingly modern. Opium, like modern drugs, was identified as a potentially deadly poison, and the text suggests it made consumers dependent (making the brave and bright stupid and unfilial and having an unspeakable effect on character). Socially, it threatened to make its adepts downwardly mobile (Wealthy and luxurious houses are impoverished by it). Beyond this, it was identified as a cause of crime and public disorder (Treachery, licentiousness, robbery, and brigandage all arise from it). Its lyrical language aside, the epigraphical message rings much like any statement condemning drugs today.

Qing dynasty China was the first state to ban drugs, or at least the first to do so on the basis of justifications that remain relevant today. The steles appeal to the spirits, called on to lend a hand to officials in hunting down traffickers, sounds a quainter note. Yet religious agitation would also arise in Europe and the United States as a powerful force for drug prohibition in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Moral stigma and religious imagery remain part of the vocabulary for condemning drug users to this day. Our Taiyu magistrate lastly made the point that opium is produced beyond the seas and that to eradicate a great scourge, its source must first be cleansed. Chinas opium came from India and the Middle East. The belief that supply could more easily be cut off because it originated abroad was, and is, darkly seductive. States are forever prone to treat their drug problems through border policing or by placing pressure on foreign countries, avoiding the unpleasant business of confronting their own citizenry. No nostrum would feed the long war on drugs more consistently than the idea that intoxicants can simply be eliminated at source.

The emperors penalties for smoking opium, introduced in 1813, were a hundred blows of the bamboo cane and one month in the cangue a type of mobile wooden pillory affixed around the head that prevented the prisoner from feeding him- or herself. Public officials caught smoking would be dismissed.

It is worth highlighting that at the time of these prohibitions, the Qing empire scarcely had a rampant opium problem. Chinas opium smokers could not have numbered more than a few tens of thousands in 1813 at most 10,000 to 20,000, if taken to mean addicts. This was a tiny proportion of its population of more than 300 million. Opium was freely available in Britain, where it was routinely taken as a painkiller in pill or drink form.

It is from these humble origins that drug control has grown, over two centuries, to achieve the far grander proportions it has today. The war on drugs did not originate in the USA. Even less did it begin, as is sometimes believed, with Richard Nixon. Nixon was not even the first American president to declare such a war: in 1954 President Eisenhower had called for a new war on narcotic addiction at the local, national, and international level. trade passed on to the League of Nations and later the United Nations (UN), turning into a global endeavour.

Accompanying this process, the set of regulated drugs expanded to involve an increasingly broad array. Opium is an addictive drug derived from a plant, a white-flowered variety of poppy, whose seed pod yields the juice from which it is made. Chemically refined, it can be transformed into a range of compounds collectively known as opiates, among which are morphine and the even more potent heroin. Consumers of opiates numbered 29 million worldwide in 2017. Finally, the prohibited list includes the plant-based cannabis or marijuana, whose use is as ancient as opiums though its recent legalization in a number of U.S. states and in two countries, Uruguay and Canada, suggests that it may one day leave the group of illicit drugs.

It is the story of this transformation that this book presumes to tell: how an ever larger group of mind-altering products came to be prohibited throughout the world, for what reasons, and with what effects. Why are such drugs illegal today? Should they be? Has drug prohibition worked? What have its consequences been? Two hundred years ago, the Jiaqing Emperor chose to launch a campaign against anyone among his subjects who dealt in or smoked opium. Today, the UN and its 190-plus sovereign members actively police and punish drug trafficking and use worldwide. How did one lead to the other?