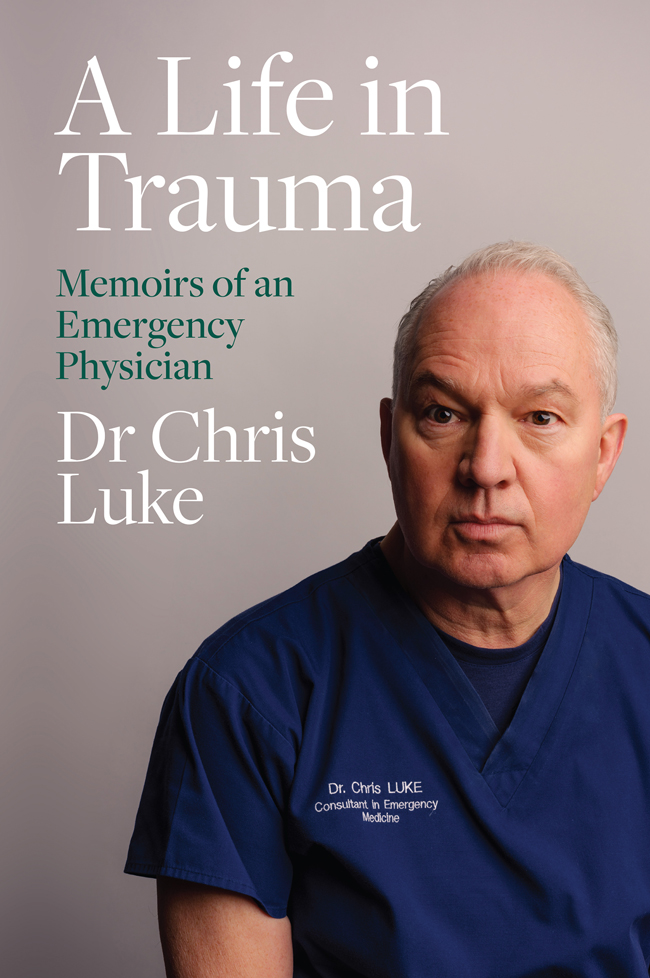

Authors Note on Emergency Medicine

Emergency Medicine is a legally recognised speciality of medical practice in Ireland, focused on providing immediate, urgently required care. It is practised mainly in hospital emergency departments (EDs); historically (and still in the UK) these units were known as casualty and then accident and emergency (A&E) departments, but the re-naming in Ireland 20 years ago was designed to make the purpose and function of the unit as unambiguous as possible. The speciality is one of the largest and fastest growing disciplines in the English-speaking world, although it remains relatively under-resourced in Ireland in terms of facilities and staffing.

There are about 28 public and six private EDs in the country. The public departments are open to all-comers in a crisis 24 hours a day, every day, but theyve been oversubscribed for decades and are often overcrowded. The main reasons for this among many are that there are too few hospital beds or step-down facilities to admit patients for long-term care; the departments themselves are often poorly designed and too small (even the ones that were opened recently); and the EDs are often perceived as the only available portal into hospital care for those on long waiting lists or those with particularly complex needs. Notwithstanding these challenges, emergency medicine has a very proud tradition of providing urgent, effective care for around a quarter of the population of the Anglophone world, as well as offering profoundly important leadership and innovation across great swathes of healthcare. I believe that Irish EDs are beacons of hope and care in a sometimes-frightening world, but they are also locations of human and organisational imperfection.

Prologue

The past is never dead. Its not even past.

(William Faulkner)

I ve always thought that the old schoolyard phrase sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me couldnt really be true. Because every teenager knows that words can wound, and every politician knows that a powerful speech can trigger warfare or bring about a ceasefire. Sadly, in my own case, mere words spelled near disaster for my career as an emergency physician. In hindsight, I suppose it was apt that it took an actual tragedy to trigger my calamitous outburst.

On 10 February 2011, a 19-seater Manx2 commuter plane left Belfast at about 8.10 a.m. a little late, but less than 40 minutes later the twin turboprop was approaching Cork airport. Unfortunately, dense fog cloaked the airport so completely that its landing lights and markings were invisible from the terminal and the flight deck of the plane, several hundred feet up in the air. Air traffic controllers instructed the pilots to circle rather than attempt landing blind, and, for the next hour, the plane did just that while safer landing conditions were sought in Kerry, Shannon and Waterford.

But the efforts to find an alternative place to land proved futile and, at about 9.46 a.m., the Cork tower instructed the aircraft to begin its descent. As the plane neared the western Runway 17, it rolled suddenly to the left, and then to the right. Its wingtip touched the ground at speed and the plane flipped over onto its roof, veering violently to the right and then ploughing through the grass beside the landing strip. At roughly 9.50 a.m., it came to a standstill, its nose buried in soil 70 metres from the centre of the runway, and both engines caught fire.

Four miles away, in the centre of Cork, I was sitting on stage in the packed ballroom of the Metropole Hotel, about to go live on air on Pat Kennys RT morning radio show. I had been invited to talk about the trolley crisis in Corks emergency departments an issue I thought exceptionally important and in need of urgent public discussion. But I was already hoping I could get away quickly, anxious about spending too long away from the busy emergency department in the nearby Mercy Hospital, where I was due to work that morning.

As I sat there, listening to the other guests, I couldnt help recalling the words of an old school friend, the son of an eminent paediatrician, whod once chided me about ventilating on the subject of healthcare: Jeez, Chris, you medics are always moaning. You just cant help yourselves.

Still, I was determined to have my say that morning. After countless cruel months, I was at my wits end with the conditions in the two departments in which I was then working, and definitely not in the mood to offer a positive spin on things. The truth was that the atmosphere in both units had turned into a noxious fug of anguish, despair and hostility, with patients on trolleys as far as the eye could see, and many more hidden in nooks, crannies, back corridors or side rooms. Standing by most trolleys, there were usually partners or adult children proactively representing the interests of the often-elderly occupants. It was like getting through a thronged obstacle course whenever a call went out for staff to hurry to Resuscitation (Resus), or to one of the cubicles for a cardiac arrest, a newly arrived road accident victim or an overdose case. And, every day, ambulances queued outside to offload their urgent cargo, while dozens of the walking wounded sat or stood for hours in the reception area, as they waited for their name to be called by the Triage nurse.

By 2011, Id endured such conditions for over twenty years, and it was obvious that things were getting steadily worse. Shortages of space, staff and alternatives to the hospital emergency department meant that the joke that A&E stood for Anything & Everything was no longer funny. It had become the default position. And the results were not just deeply unpleasant conditions for the sick and their carers they were genuinely toxic.

Some of my medical colleagues had calculated that dozens of people were dying every year in Irelands crowded emergency departments (EDs) because the urgency of their conditions was not recognised amid the mayhem. Self-evidently, our patients could not receive the sort of humane, effective and well-organised care of which we all dreamed, and for which we had trained for so long and so hard. And the most alarming consequence for me was that experienced nursing staff were leaving in droves, while those that stayed seldom smiled. In truth, then, I was well beyond exasperated. I was actually seething with an anger that was completely at odds with the light-hearted atmosphere of the radio show.

Inside the crushed aircraft, the two pilots and four passengers at the front had been killed instantly by a combination of head, chest and abdominal injuries. Six other occupants towards the rear were trapped in their seats, in total darkness, as the lights went out on impact. One of them, a regular commuter between Cork and Belfast, subsequently recounted how the crumpled fuselage was pressing upon his head, and he felt he was being suffocated as mud and water poured into the cabin.

He could also hear the screams of a woman nearby, who later remembered that in the first few seconds post-impact, she held her neighbours hand and they prayed together, terrified that theyd survived the crash only to be incinerated by the flames discernible through the windows on both sides. Moments later, there was a banging on the sides of the plane and its windows, and cries of Dont panic! Were going to get you out! from the airport rescue teams. The survivors werent long receiving assistance. A fleet of eight ambulances was already on its way, along with numerous fire, rescue and airport police vehicles, bearing about two hundred personnel to the crash site. And, soon after, a tent was hastily erected near the scene of devastation to serve as a temporary morgue while, inside the downed aircraft, the grim task of medical assessment of the victims, living and dead, got underway.