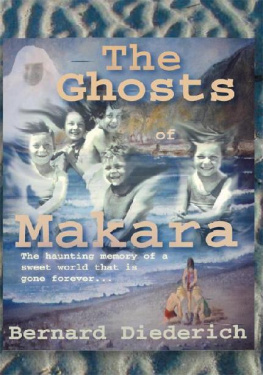

THE GHOSTS

OF

MAKARA

Growing Up Down-Under In a

Lost World of Yester years

Bernard Diederich

Copyright 2002 by Bernard Diederich.

Library of Congress Number: | 2002092291 |

ISBN : | Hardcover | 1-4010-6035-8 |

Softcover | 1-4010-6034-X |

eBook | 978-1-4691-1277-0 |

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing

from the copyright owner.

To order additional copies of this book, contact:

Xlibris Corporation

1-888-795-4274

www.Xlibris.com

15464-DIED

Contents

Also by Bernard Diederich

Papa Doc: The Truth About Haiti. With Al Burt.

Trujillo: Death of The Goat

Somoza: The Legacy of U.S. Involvement in Central America

Dedication

This memoir is dedicated to Mum and Dad, Stellamaris, Quita, Brian, Geoffrey and Patrick and all those others who were part of my extended family, but who are no longer with us. I owe so much to their love and guidance as well as to my non-ghost patient spouse, Ginette. Natalie, Jean-Bernard and Phillippe, our beloved children, fell in love with New Zealand on their early childhood visits and often would ask, Tell us what it was like growing up in Makara and New Zealand. And my grandson Alexandre Bernard who cannot wait to visit grandpas homeland.

A happy family is but an earlier heaven.

-Sir John Bowring (1792-1872, English statesman

If children are a gift of God, growing up in a large and contented family is a benediction of the saints. This book is a very personal memoir about such a familymy family. And these recollections are made all the more wistful by the time period and the setting in which my sisters and brothers and I, cosseted and disciplined by a solicitous Irish-New Zealand Mum and a hard working German-Irish-New Zealand Dad, grew into adolescence.

The time was the 1920s and 30s, a period encompassing the Great Depression and presaging World War IItruly the end of an era. The setting was a rocky, windswept, virtually unknown outcropping of New Zealand known as Makara Beach.

That was where Ior, more specifically, we Diederich offspringplayed, fought, explored, learned about both our colonial roots and New Zealands indigenous Maori culture, and huddled in our beds at night listened to the fearful howling winds, which childhood imagination transformed into the ghosts of Makara.

And it was from Makara and the nearby city of Wellington that I sailed away, as a sixteen-year-old cabin boy on the majestic four-masted barque PAMIR, its 34 sails billowing in the wind, to see the larger world. It was a great privileged to sail before the mast and experience the manner of travel that brought my ancestors to New Zealand in the nineteenth century.

Today, few can afford the luxury of a big family. Families have gotten smaller, for understandable, if often regrettable, reasons. Health costs and sending a child to college can devour a lifetime of saving. Both parents frequently must work, adding to the normal stresses of the family environment. A typical modern child grows up with television as a substitute Mum.

To me, it is truly heart-rending to realize that many a youngster todaybused in the morning to impersonal schools in distant neighborhoods, relegated in the afternoon to day-care centerswill never know what it is like to come home to a waiting Mum, and join her and Dad and brothers and sisters at a convivial, TV-free dinner table.

As I note in my Epilogue, they are gone nowMum and Dad; my big sister Stellamaris who lived her adult life as a caring Sister of Mercy nun and died of cancer in 1986; my sister Marquita (Quita) with a wonderful family of six children in Australia who died also of cancer a decade later; even that four-masted barque that carried me away, itself sunk in a hurricane off the Azores in 1957 with eighty hands lost.

And even the ghosts of Makara, those ever-present gales, seemed to have lost their eeriness whenever i revisited our old beach to contemplate our little white frame house, still standing but occupied by strangers. All that is left, in a material sense, are the sepia photographs of our family in those happy days.

Thank God, however, not every treasure in life is a material one. i still have my memories, an enduring trove, which i hope all who read these remembrances will share.

Bernard Diederich Pinecrest, Florida March 2002

Be gone Sweet Ghost, O get you gone!

Or haunt me with your body one;

And in that lovely terror stay to haunt me happy nightand day.

For when you come I miss it most, Be gone, Sweet Ghost!

Oliver St. John Gogarty.

They call it Gods own country. But as a child, I often believed that God had failed to bless our small corner of New Zealand and that the Devil and all his malevolent allies had taken control of this disturbing end point of land. Today New Zealand is known as the place where the movie epic, The Lord of The Rings, was made. Remarkably, one of the locations in which it was filmed was Makara, our familys wind-whipped niche of New Zealand. Makara was truly J.R.R. Tolkiens Middle-Earth, and we children could easily have been mistaken for barefoot, red-cheeked, happy Hobbits. Makara though was full of both beguiling beauty and intimidating ugliness; it could be at once forbidding and friendly, insulating and liberating.

Notwithstanding its paradoxical setting, Makara Beach was our childhood sanctuary where my brothers, sisters and I shared in coping with the forces of nature, while escaping the worst of the economic maelstrom of the 1930s known as the Great Depression.

Summer in Makara could be heaven. Daisies, buttercups and red clover blanketed the paddocks. Foxgloves and honeysuckle grew by the roadside, and there were even clumps of yellow daffodils on the hills. Freshly mown hay was the most exquisite perfume. Our rivers surface bustled with ducklings and goslings. The beach itself, giving way to the deep blue waters of Cook Strait, was warm and hospitable.

Gone during summertime was the iodine odor of seaweed dragged from the deep by the angry winters sea. Skylarks and yellowhammers were everywhere. Sedately the kingfisher perched on a bough over the river before the Hawkins swing bridge, contemplating its next meal near the waters surface. The big bumble-

bee arrived along with the flowers. Fly swatters were active and the sticky yellow bug catchers hung from kitchen ceilings were soon black with dead flies. There was no protection however against the ubiquitous, merciless, little sand flies.

For all the bedeviling insect life, we children roamed barefoot and free. Alas, nevertheless, a strong, bone-chilling southerly wind could quickly cloud those warm, glorious days of summer, sending us scampering home to seek shelter. We could experience all four seasons in a single day.

Winter, by contrast with Makaras summer, was raw, bleak and paralyzingly cold. The hills turned brown and then purplethe color of our lipsand took on the loneliness of a windswept English moor. The farmers, bundled up in gumboots and oilskins, were dark blobs on the horizon as they went about fencing their fields and cutting scrub. It was also when farmers shoed their horses. In sum, our rustic childhood romance with Makara had a touch of Wuthering Heights enduring and tempered only by the wind.