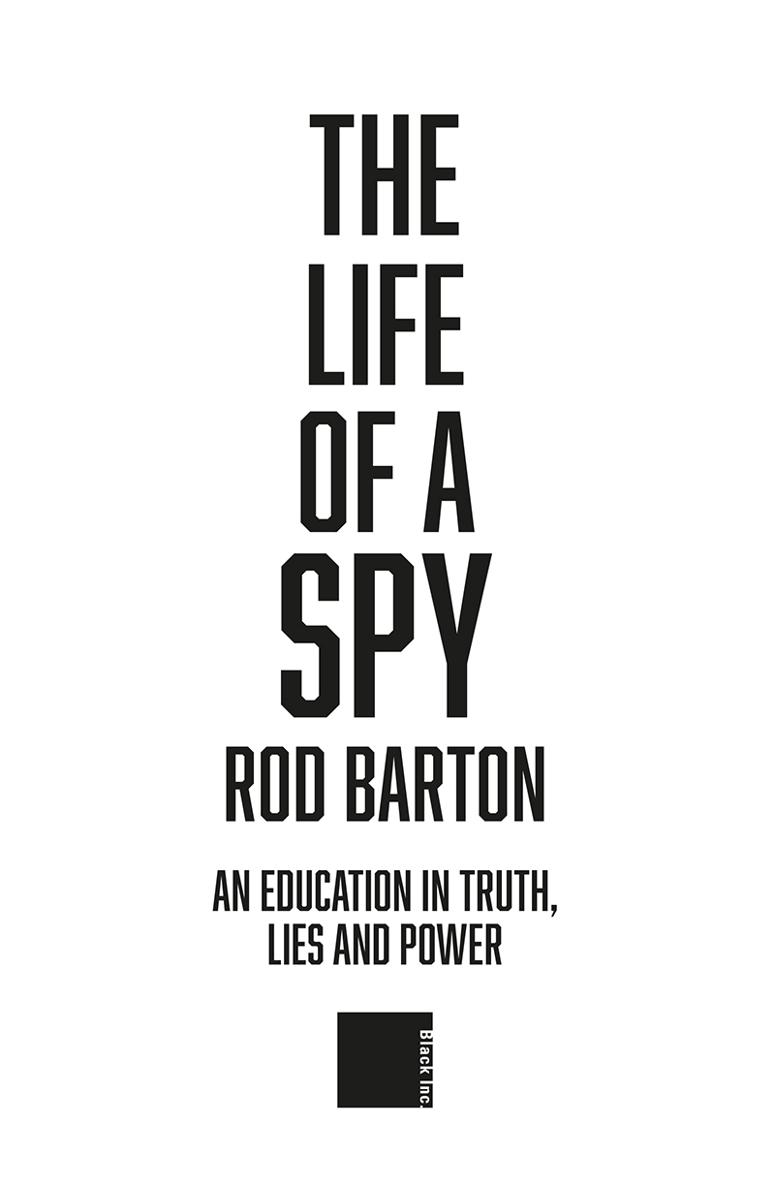

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright Rod Barton 2021

Rod Barton asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760642778 (paperback)

9781743821763 (ebook)

Cover design by Regine Abos

Text design by Tristan Main

Typesetting by Typography Studio

Cover photograph by Rockfinder / Getty

AUTHORS NOTE

As our helicopter, piloted by the German Luftwaffe, flew over the western deserts of Iraq, I heard one of the engines splutter and stall. We quickly lost altitude and landed unsteadily on the burning sands. I climbed out and stared across the windswept plain, the heat shimmering to the horizon, and wondered what I was doing here, in the middle of nowhere.

I sat in the shade of the fuselage in the oven-like heat, waiting for the Germans to send a rescue helicopter, reflecting on what an unusual situation I found myself in. I was an intelligence officer with the Australian government, but had moved on from sitting in an office analysing data to participating in an operation I could not have imagined at the start of my career.

And as it turned out, my career only became more remarkable from there.

I was certainly no James Bond with a licence to kill, but I did experience some events that would have intrigued him. I worked with the British intelligence services and with, and for, the CIA. I had guns pointed at me, death threats issued, a price placed on my head. On the less deadly side, I also became an expert in bee excrement and collected Antarctic penguin eggs.

In this book I recount the strange circumstances of my recruitment to the intelligence world and some of the adventures of my professional life. From a naive junior intelligence analyst, through working for Hans Blix as a weapons inspector, to my clashes with the CIA and my wrangle with the politicians who led Australia to war in Iraq in 2003, I have seen a unique side of intelligence operations around the globe, and witnessed things that have both alarmed and reassured me about the capabilities of our intelligence agencies.

This book is not intended as a deep study in the theory and practice of intelligence. It is to inform and, I hope, entertain. Much of the narrative focuses on events in the lead-up to the war in Iraq, and the consequences that followed. I believe there were no winners in the so-called War on Terror, but readers will have to decide this for themselves.

Spies never want to reveal much. For security reasons, there are still some operational details I cannot disclose. Many names have been changed to protect the innocent and, in some cases, the not-quite-so innocent.

Rod Barton

February 2021

CHAPTER 1

GRUNTERS AND GROANERS

It is a mistake to look too far ahead. Only one link of the chain of destiny can be handled at a time.

Winston Churchill

On stage at St Philips Christian College, a private school on the New South Wales central coast, I was tense. I had given many talks and lectures, but this was different. Usually I spoke about the nature of intelligence work or the formulation of United Nations Security Council resolutions, or even weapons of mass destruction and the politics of disarmament. This time, I planned to speak about my work as a weapons inspector in Iraq. Although I didnt want to dumb it down, I couldnt venture far into theory, politics or technicalities. Fifteen-to eighteen-year-olds are a tough audience.

The students had gathered in the assembly hall, some bussed in from nearby schools, so the mob had now grown to more than 200. I might have had more than one gun pointed at me, but now I was nervous in front of a bunch of schoolkids.

As we waited for the last stragglers to take their seats, the principal leaned over and whispered, Dont worry if some of the students get up to go to the toilet and dont come back. Seeing my alarm, she confided, This happens when we have guest speakers. Its nothing to do with you.

I stood at the podium while the principal introduced me and looked at the crowd contemplatively. Most were staring at their phones or chatting. A small group of boys at the back were flicking spitballs at each other. I wondered who would be left in the hall by the end of my talk.

So I broke a long-standing rule and began, slowly and steadily: I was a spy for the Australian government.

Down went the phones. The arcs of spittle-laden projectiles ceased.

Not one student left during the talk. Afterwards, the principal told me that this was a first.

No self-respecting spy would ever out themselves as one. The job is intelligence officer, and it comes in different shapes and forms: some collect intelligence from overseas, perhaps through remote electronic surveillance or by running operatives in foreign countries; analysts make sense of what is collected, and assessment officers put this analysis into some sort of context.

Officially, I was an intelligence analyst and an assessment officer, and later a director of intelligence, but when I was posted overseas, the boundaries between collection and analysis became blurred, as did my role in the intelligence world. In that sense, I was a spy.

* * *

My interest in intelligence began early. I was born in the industrial north of England, in a rather bleak post-war Britain, where my father was a research chemist for a soap factory, and my mother a primary-school teacher. They sought a better life for themselves and their four children, so in 1957, when I was nine, they decided to emigrate to sunny South Australia. The choice of destination was influenced by my maternal grandfather, who had run away to sea as a teenager and gave glowing reports of his port of landing in 1896: Glenelg. I knew what a palindrome was due to this family lore. And so we became Ten Pound Poms.

However, palindromes were not in my future. We moved instead to the new migrant town of Elizabeth. It was a rough-and-tumble place with a mix of cultures, as rock star Jimmy Barnes, who also grew up there, detailed in his biography Working Class Boy. Most migrants were from the United Kingdom, but there were also sizeable numbers from Germany and the Netherlands. Some of my friends had names like Jrgen and Rudolph, which I considered exotic, and I became interested in key differences between us, such as their speech patterns and what was in their lunchboxes.

Elizabeth was very much a working-class town, especially with the opening of the Holden car factory in 1963. But across the railway tracks there was another large employer: the federal governments Weapons Research Establishment. Some top British and Australian scientists worked on secret projects at WRE. I became curious about what lay behind the double rows of barbed-wire fencing. Occasionally there were exciting clues, such as the roar of static motors, which I later discovered were live-fired in rockets at Woomera, in the states far north.