Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2017 by Edward J. Branley

All rights reserved

: Metal sign at the front door of 1201 Canal Street. Author photo.

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.269.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017940959

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.862.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Amanda Irle, acquisitions editor at The History Press, for shepherding me through the THP process. Special thanks to the indomitable Dara Rochlin (@BookDoctorDara) for her editing and research skills. Much love to Jennifer Duplantis, Susan Kagan, Christine Stephens, Susan Vollenweider, Melissa Case, Lisa Graves and Tricia Cohen, who all keep me upbeat and smiling. A UNO-alumni tip of the hat and thanks to the staff at the Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans, especially James Hodges of the Louisiana and Special Collections section. UNOs library is the repository for the Krauss Collection, and James was wonderful about putting up with my requests for stuff that was up on the fourth floor while the section was in its temporary second-floor abode. Thanks to everyone in the Krauss community of former employees and shoppers who shared wonderful memories and gave me a feel for aspects of the store I didnt know about. I am very grateful to Hugo Kahn, the last president of Krauss Co. Inc., for meeting with me and sharing some of his memories of the store. A hearty BMHS Crusader wave to Ryan Bordenave, whose expertise on Canal Street and the CBD was invaluable. Thanks to Drew Walsh, James Karst, J.D. Thomas, Carlos Froggy May and the other denizens of the various New Orleansrelated Facebook groups who contributed tidbits and ideas along the way. Thank you, Cait Gladdow and Mark Samuels for your help with the research process. I raise my glass to Chuck Taggart in thanks for his red beans and rice recipe. Hugs and love to all my friends who supported the project.

All my love to my wife, Helen, and our boys, Kevin and Lieutenant Justin Branley, USN, who are both too young to have shopped at Krauss but patiently let me tell them about the store. Thanks to all my teachers, as well as all the librarians and archivists whose hard work over the years makes writing a book like this much simpler now. Heartfelt thanks to all the folks at Wakin Bakin on Banks Street in Mid-City. Im very appreciative that Conrad and Zak didnt charge me rent, since 90 percent of the book was written in their wonderful breakfast place.

1

Gumbo

Gris-Gris Gumbo Ya-Ya

Mac Rebennack, aka Dr. John, The Night Tripper

Gumbo is a wonderful soup that combines many flavors and ingredients, turning them into a unique dish that is revered in New Orleans. Its the perfect food analogy to the city of New Orleans itself. And a food analogy is the perfect way to describe New Orleans in the first place.

Gumbo has as many variations as there are cooks who make the soup: Chicken-and-sausage gumbo. Seafood gumbo. Okra. Fil. Oysters. Crawfish? Not in my gumbo, a chef I know says. Turkey gumbo, made on the day after Thanksgiving. Each one is unique. Each one makes up the big picture.

New Orleans isnt just one big pot of gumbo. The city is a collection of pots. Downtown gumbos include the French Quarter, the Treme, along Bayou St. John, the Sixth Ward and many other neighborhoods. Uptown gumbo is the Central Business District (CBD), the Warehouse District, the Garden District, Faubourg Bouligny, the University District, Carrollton. Back-of-town gumbos exist on both sides of Canal Street. Then theres Canal Street itself. The 140-foot-wide main street isnt merely a dividing line but rather a gumbo in and of itself.

At midnight in the Quarter to noon in Thibodaux, I will play for gumbo

Jimmy Buffett, I Will Play For Gumbo

Like gumbo recipes, New Orleans has changed over time. At the start of the twentieth century, the city was the second-largest port in the United States. It was a city adjusting to twenty years of unprecedented expansion after the Civil War. Immigrants from all over Europe, but particularly from Italy and Germany, made their way to New Orleans at the end of the nineteenth century, shifting the flavors of the gumbos that are the citys neighborhoods.

When the Americans took over New Orleans in 1803, they didnt really bring a gumbo recipe with them. The Anglo Irish brought their own flavors, though, and those blended into the recipes that were already simmering on the stoves. By the 1850s, residents of the city could taste many variations of gumbo, and their reports of how wonderful this was attracted even more people to the magic.

While New Orleans was very much caught up in the political conflicts of the late 1850s that led to the formation of the Confederate States of America, New Orleans recognized that the port was paramount. When it was clear that the blockade of the port by the Union navy was killing the city, Farraguts invasion from the mouth of the Mississippi in April 1862 was a force that locals could not withstand. Union occupation spared New Orleans the fate of Atlanta and enabled the port to continue to grow. Reconstruction allowed the merchants operating shops and stores on Canal Street to re-stock and expand. By the 1880s, dry goods stores supplied a number of ingredients needed to keep the gumbos simmering.

Steamboats moored along the Mississippi River at New Orleans. Library of Congress.

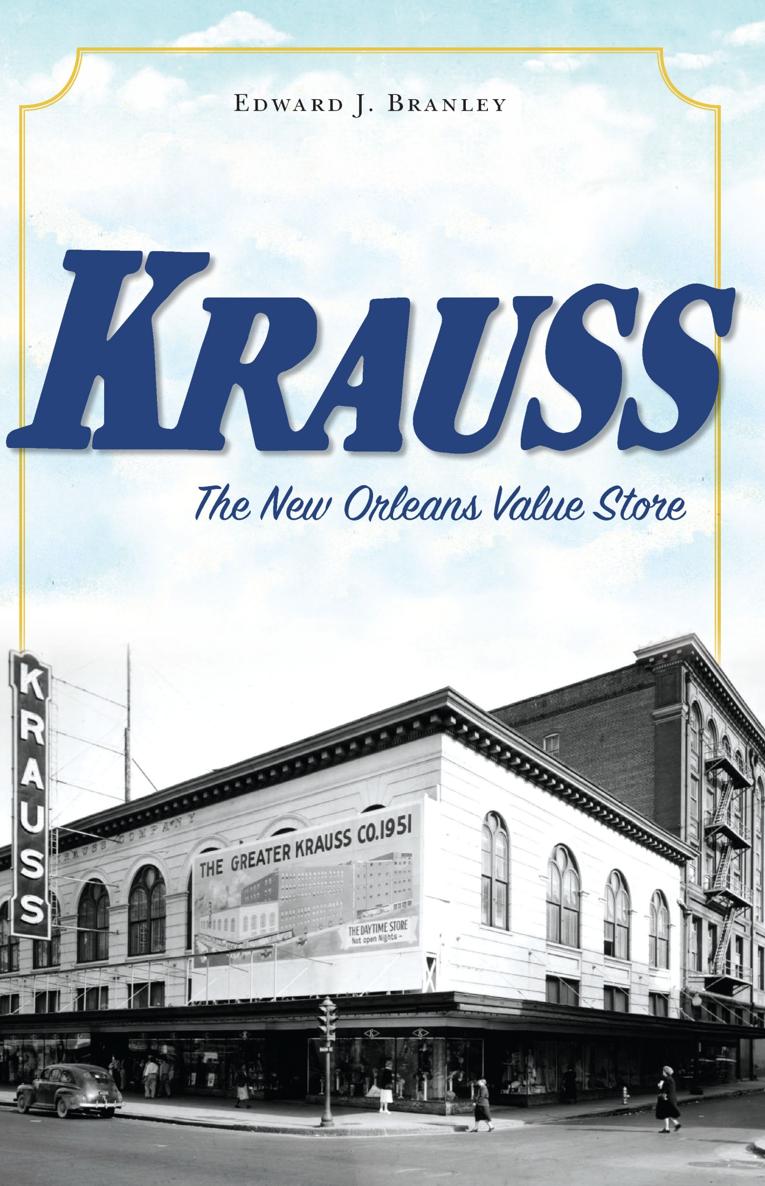

The 1890s brought a huge change to the retail landscape of New Orleans. S.J. Shwartz, financed by his father-in-law, Isidore Newman, opened the first department store in the city, Maison Blanche, in 1895. This development inspired other New Orleans merchants to follow suit, and in 1903, the Krauss brothers shifted focus from niche-market sales to the general-merchandise model. The gumbo pots of 1903 were flavorful and diverse.

Take the French Quarter, the citys first neighborhood. When Adrien de Pauger laid out the plan for the original city in 1725, New Orleans was a French city. The French influence dominated until control of the city was passed to the Spanish in 1766, lest it become one of the spoils of war between the French and the British. The Spanish tweaked the gumbo recipe for twenty years, and then they were forced to totally re-create the recipe after the Great Fire of 1788. French-built homes and buildings were replaced with new ones that followed strict building codes. Spanish Colonial architectural influences left us with the high-walled houses focused on central courtyards, their beauty hidden from passersby on the streets. French priests tending their flock found themselves under the administration of Spanish bishops sent from Havana. The mix of languages, colors and political passions in the port appeared impossible to navigate, but the cooks blended the various ingredients into their gumbos.