Published under license in Great Britain by

LEO COOPER

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

ISBN 0 85052 799 6

A CIP catalogue of this book is available

from the British Library

For up-to-date information on other titles produced under the

Leo Cooper imprint, please telephone or write to:

Pen & Sword Books Ltd, FREEPOST, 47 Church Street,

Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Telephone 01226 734222

SPOTSYLVANIA WAS A CROSSROADS both literally and figuratively. In 1864 it was a sleepy town where two important local roads joined, the Brock and Fredericksburg Roads; history most likely would have ignored it had the Civil War never been fought. But it also became a crossroads for armies: an objective of both the Army of the Potomac and Army of Northern Virginia as they battled each other on the fields and farms throughout central Virginia, struggling to achieve victory at the bidding of their commanders. More significantly, it was a crossroads for tactics as well: the stand up and shoot it out linear firing lines of the Napoleonic era were slowly being transformed into anachronisms by new weaponry that delivered more lead, more accurately, with more speed. New tactics had to be created to meet this transformation and at Spotsylvania such new methods were attempted. Spotsylvania was also a crossroads for two men, both straining to conquer the other and win final victory for their cause: Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee.

For Grant, victory was to be achieved in his Virginia campaigns by alternating between maintaining his armys momentum and the continual application of force. These elements were the basic foundation of his strategy and tactics; the use of both had been honed to near perfection during the generals progress throughout the war.

Grant arrived in Washington in March 1864 to take on the critical post of commander of all the Union armies. The western general found himself in charge of the massive military machine the Union was fielding to defeat the South: 745,000 troops spread out across the young republic in nineteen military districts. Managing this huge force was an incredible task for the day. It might have been prudent to undertake the task in the confines of Washington, D. C, as did his predecessor in the job, Henry W. Halleck. But Grant chose to conduct his affairs while traveling with the Army of the Potomac, which was to be Grants primary tool for campaigning in Virginia the coming spring. It was a force that had known sporadic victories and disappointing defeats throughout the three previous years of war. Its victory at Gettysburg, fought from 13 July 1863, still loomed large. But the composition of the force had changed significantly from its appearance at Gettysburg before the beginning of Grants eventual movement south, even from its earlier historic battles in 1862 and 1863. At Gettysburg, the army fielded seven corps, but now several of these had been shed: two had been sent west and two more were disbandedto the dismay of their troops who strongly identified with their old unitsand were used to strengthen the remaining forces, the II, V, and VI Corps.

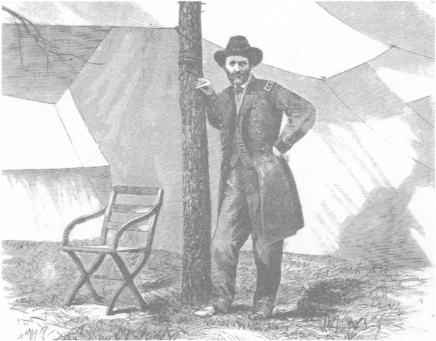

General Ulysses S. Grant

By the time the Army of the Potomac got on the move, it had almost 100,000 men. The II Corps under the command of Winfield Scott Hancock was four divisions strong, the V Corps was also composed of four divisions, and the VI had three divisions. However, the numbers sported by this huge force were somewhat deceptive. Actually, it was leaking strength like water through a sieve as time passed. Its power was decreased not only through casualties in coming battles, but from units that had signed up for three years of fighting back in 1861 whose terms of service were now almost up. Some of these troops fighting capabilities were lost even before they left the armyneedless to say, not a few of the men in these commands were not eager to fall victim to shot and shell just before the time came to be sent home.

Despite this loss of troops, the Army of the Potomac could count on several leaders of superior quality. At the armys helm was the victor of Gettysburg, Major General George Gordon Meade. Meade was certainly capable and had seen some of the Army of the Potomacs greatest battles.

Serving under Meade and leading the Army of the Potomacs three corps were also three dedicated, experienced, and solid fighting generals. Winfield Scott Hancock, in charge of the II Corps was perhaps the best Union corps commander of the war. The other two corps commanders were not as distinguished, but had commendable records. Gouverneur Warren had some experience leading troops, but was a staff officer by the time of Gettysburg. Even though that position might have been an inglorious one, it was Warren who had organized the defense of Little Round Top and helped secure that position from heavy enemy attacks. John Sedgwick with the VI Corps was beloved by his men and by the Army of the Potomacs leadership; unfortunately fate and a Rebel bullet combined to make his service in the coming campaigns for Richmond a short one. In command of the Army of the Potomacs cavalry was the firebrand, Philip Sheridan, one of Grants western comrades.

Overall, the Army of the Potomac was subject to two odd command anomalies. The first stemmed from Grants decision to accompany the Army of the Potomac on its move south. He claimed Meade was given a free hand to direct the force; perhaps an unrealistic claim, for inevitably, Grant often saw fit to issue orders over the forces movements and campaigns. This interference effectively gave the army two commanders unequal in power: Grant the superior and Meade the subordinate in the very army he was supposed to be leading. The second anomaly in the command structure of Grants army was the IX Corps, commanded by Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, which was being attached to the army for the offensive. This force contained twenty thousand soldiers in four divisions, including one of African American troops. Because of Burnsides rankhe had commanded the Army of the Potomac in late 1862 and early 1863 until dismissed for his failuresthe IX Corps operated under Grants command instead of Meades; this odd arrangement basically led to an independent corps attached to the rest of the army.