Victor Sebestyen - Budapest: Between East and West

Here you can read online Victor Sebestyen - Budapest: Between East and West full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Orion, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Budapest: Between East and West

- Author:

- Publisher:Orion

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Budapest: Between East and West: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Budapest: Between East and West" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Budapest: Between East and West — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Budapest: Between East and West" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Jessica

CONTENTS

Towards the end of the Congress of Vienna in the spring of 1815, Klemens von Metternich, the Austrian Foreign Minister, took a young British visitor in his carriage to the eastern edge of the city. As the pair descended the steps, the eminent Habsburg statesman pointed his finger to the road towards Hungary and declared: Look, thats where Europe ends out there, [Hungary] is the Orient.

Half a century later William H. Seward, President Lincolns Secretary of State, went on a journey around the world immediately after his term of office ended. In summer 1869 he arrived in Pest

This is a constant theme, as alive in the twenty-first century as in the nineteenth. Throughout history Hungary and its capital have been a significant part of Western Europe yet at the same time apart from it a point made repeatedly now by contemporary Hungarians. On the morning of 15 April 2016, in one of Budapests grandest central squares, Viktor Orbn, Hungarian Prime Minister for more than a decade, made a typically pugnacious speech. Throughout history we Hungarians more often than not all alone have stood as the bridge between East and West and we suffered as a result, he told a cheering crowd. Repeatedly we have saved Western, Christian civilization from catastrophe and destruction by invaders from the East. In the Hungarian context this was an unremarkable comment, more a statement of fact than rhetoric. Most Hungarians of both Left and Right would see it as a self-evident notion expressing a deep-rooted idea about nationhood that has always resonated with people from Budapest and still does.

Though much of it is similar to other lively, bustling European cities, the sound of Budapest is different. The unique, orphan language makes it so. The roots of Magyar, Finno-Ugric, originally or so it has been assumed derive from the steppes of Kazakhstan. Hungarian is unlike any other European tongue. Few outsiders, overhearing snippets of conversation at a coffee house or in the Budapest metro, would have any idea of what the people they were listening to were talking about. We are a lonely people, the Hungarian national poet Sndor Petfi wrote in the 1840s. This is equally true today.

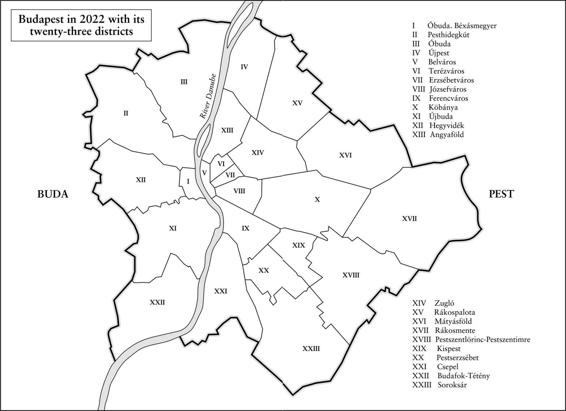

A cursory look at a map shows why Budapest has always been an important place. It is close to Europes geometric centre; it is at the crossroads of geographical regions and of civilizations, at the intersection of ancient trade routes. Mountains that gradually slope into gentle hills converge on a great river, the Danube, and a vast plain. Mediterranean Latin, Alpine German and Slavic peoples meet here. This is the focal point of Roman Catholic, North European Protestant and Greek Orthodox/Byzantine cultures.

Budapest became the capital of Hungary and in many respects the centre of the Danube region because of its favourable strategic location along a convenient traffic route. Modern Budapest grew along deliberately set, albeit repeatedly disputed and modified, plans. It is a city that was designed and built according to a scheme. Yet its most distinctive marks were left by involuntary forces wars, revolutions, floods. Altogether Buda, over many periods the administrative centre of the Kingdom and then the Republic of Hungary, suffered thirteen sieges and was left in total ruins five times. Invaders have come and gone, empires have conquered, occupied for centuries or decades, and left a few footprints behind: the remains of a Roman bath house complete with wonderfully preserved mosaics stand next to a Soviet-style five-year-plan apartment block that is already falling apart. As I hope to show, Budapest has grandeur, if faded around the edges, beauty in a gritty, lived-in sort of way. It is a city humbled by time and the ferocious moods of history, as the great poet George Szirtes put it.

Wallis Simpson, Theodore Roosevelt, Benito Mussolini, Hans Christian Andersen, the great tenor Luciano Pavarotti and the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, were all agreed: the best thing about Budapest is its position. With the Danube, Budapest forms one of the most beautiful cityscapes that exists along a river, the novelist Evelyn Waugh thought. It is the most beautiful in Europe. Budapest is the place of my birth, and I do not pretend to be objective about its beauty and charm, though, as I shall also show, behind the charm lies much darkness and cruelty.

For much of my own lifetime, Budapest was the lonely place described by Petfi, cut off from the West, positioned unhappily behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War, a colony of a tyrannical empire: the USSR. Physical reminders of the Soviet occupation, which ended only in 1989, are dotted around the citys skyline. Several public buildings are still pockmarked by bullet holes, deliberately preserved, to remind visitors and Hungarians alike of a trauma that was a defining moment in the history of modern Budapest: the 1956 Revolution, the event that took me from the city.

I was an infant when my parents, brother and sister fled Hungary as refugees immediately after the failed, tragic Uprising. I didnt return to Budapest until my early twenties; nobody in my family was allowed back there until then. I recall nothing from childhood about Budapest, yet I was steeped early on in Hungarian folk memory.

My parents loathed the ghastly turns of history that forced them from their home the disastrous results of two world wars, fascism, Nazi German occupation, Soviet Communism. But they were never entirely happy in exile. Around our dinner table they talked wistfully of Budapest, rather as characters from a Chekhov play sighed the name Moscow. My mother used to speak of entire days spent talking in coffee houses, surely the best invention, and perhaps the most long-lasting, of Habsburg Mitteleuropa . My father talked of music, Bartk, Kodly and evenings at the Vigad, the wonderfully atmospheric Baroque concert hall by the Danube. My sister recounts winter days spent skiing almost from the front door of the family home in the Buda Hills down towards the city centre, a run still just about possible if performed with care and skill, at dawn before the rush hour. My brother remembers a boyhood adventure, sitting atop the turret of a Russian tank captured by insurgents during the 1956 Revolution.

I started going to Budapest occasionally as a visitor from the late 1970s to see distant relatives who had remained in Hungary. Later, as a journalist covering the collapse of the Soviet Empire in the 1980s, I sometimes went several times a year on working trips. I then began to know the city intimately.

Budapest was the easiest place in Central/Eastern Europe in which to operate as a reporter. People were relatively free to talk, surveillance was almost non-existent and the food and wine were better than anywhere else in what was then called the Soviet bloc. It was the merriest barracks in the camp. This book is the result of scores of visits to Budapest, including many months there researching my first book, written to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the 1956 Revolution. It is informed by using the knowledge of dozens of locals. It will be about the citys good days and bad, its sights and sounds, a portrait of the place and its people. It will take the story to the present day, when, once again, people in Budapest struggle with their identity and question how to be European and separate from Europe at the same time. It will look at Budapests literature, its music, its history, its cuisine, politics and the essential role played by its Jewish population when Budapest was often referred to as Judapest. I will describe the ascendance of the city in the decades leading to the First World War most of Budapest still looks like a nineteenth-century city its decline into the maelstrom of the twentieth century, when it was all but destroyed, and its extraordinary rebirth in the twenty-first, when, after London, Paris and Rome, Budapest receives more tourists than any other capital in Europe.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Budapest: Between East and West»

Look at similar books to Budapest: Between East and West. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Budapest: Between East and West and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.