1946

1946

The Making of the Modern World

VICTOR SEBESTYEN

MACMILLAN

To Paul Diggory and Wendy Franks

Contents

List of Illustrations

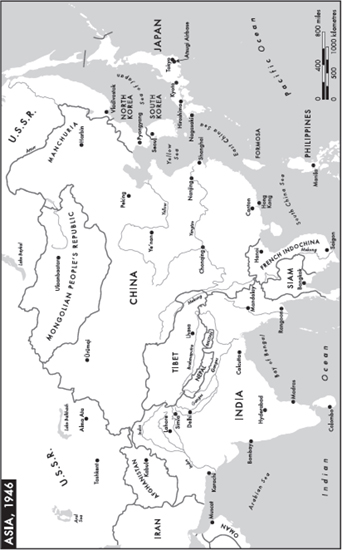

Maps

Introduction

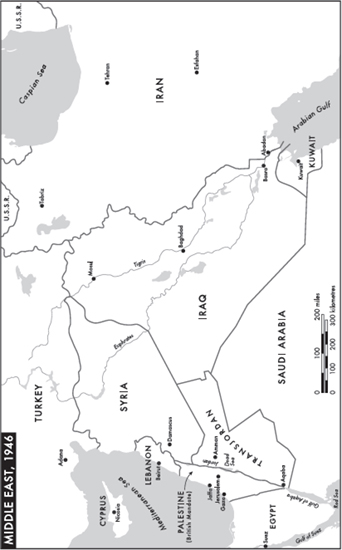

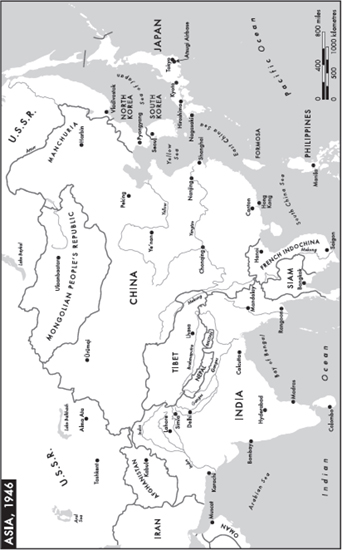

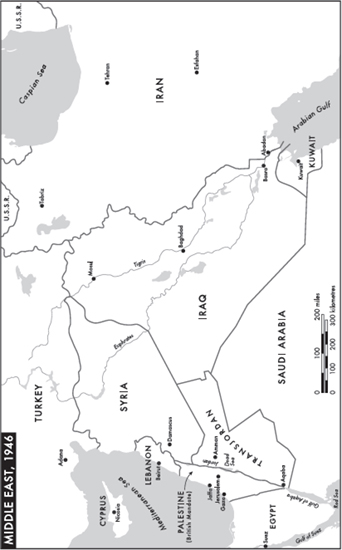

As a journalist, I have covered events ranging from the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the former Soviet Union to the cycle of violence and counter-violence in the Middle East over the existence of Israel and Palestine. Throughout, America has dominated as the worlds superpower. During many visits to India I have seen a desperately poor country, stuck in the past, transform itself into a vibrant society, looking to the future. China moved from permanent revolution to a form of rampant capitalism run by people calling themselves communists. When, as an historian, I tried to trace the roots of all these events and stories I returned continually to one reference point: 1946. The immediate post-war year laid the foundations of the modern world. The Cold War began, the world split on ideological lines, and Europe began to divide physically on two sides of an Iron Curtain. Israel would not come into being for two years, but 1946 was the year the decisions were made to create a Jewish homeland, with consequences that have remained so fateful since. It was the year independent India was born as the worlds most populous democracy, and old Britain as a great imperial power began to die. All the European empires were dying, though imperialism has lived on in various forms. It was the year the Chinese communists launched their final push for victory in a civil war that led to the re-emergence of China as a great power. This story aims to show how decisions taken in 1946 and the men and women who took them shape our world now.

There was little optimism in 1946, anywhere. At the start of

Churchill was speaking of Europe, but he could also have been talking about large tracts of Asia. He feared, as many rational people did, the arrival of a new dark age with all its cruelty and squalor. In no other war had so many people been killed in such a short space of time around sixty million in six years. Now the World War had stopped, but the dying had not. The moment of liberation the previous year had been exhilarating, but soon the reality emerged. Civil wars would continue for the next four years in China and Greece. There were rebellions against the Soviets in Ukraine, where nationalists also fought Poles in a brutal conflict that cost more than fifty thousand lives, and wars of independence flared up in various parts of Asia. Despite the Holocaust, after the war outbreaks of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe, hard to explain to a modern reader, claimed the lives of around fifteen hundred Jews who had somehow managed to escape the Nazis.

In much of Europe there were no schools, virtually no transport links, no libraries, no shops there was nothing to sell or buy and almost nothing was manufactured any longer. There were virtually no banks, which didnt matter all that much as moneywas worthless. There was no law and order; men and children roamed the streets with weapons, either to protect what they possessed or to threaten the possessions of others. Women of all ages and backgrounds prostituted themselves for food and protection. Morality and traditional ideas of ownership had changed utterly; now the imperative was usually survival. This was how millions of Europeans lived in 1946.

Berlin and Hiroshima provided the most powerful images of the war: in both cities around three-quarters of the buildings had been destroyed by Allied bombing. But from the Seine to the Danube delta the heartland of Europe had been ravaged. In China, the Japanese, before their defeat, blew up all the dykes along the Yellow River, flooding three million acres of good farmland that took three decades to recover and caused enduring hunger for millions.

There was mass starvation and economic collapse. In the Eastern half of Germany, Ukraine and Moldova, around three million people died from hunger in the eighteen months after the war. In the Polish town of Lww, the story that a mother driven mad with hunger killed and ate her two children barely made the newspapers. In Hungary inflation reached an unenviable world record of 14 quadrillion per cent (thats 15 noughts). Worthless currencies throughout Europe were replaced by bartering in cigarettes or scrounging from foreign armies. The northern hemisphere was swamped with refugees, particularly in Central Europe where prisoners of war, forced labourers and emaciated survivors of Nazi concentration camps were all grouped by the victorious Allies as displaced persons.

After the First World War, borders were shifted and new countries were invented, but people were left in place. In 1946 the opposite happened. The Red Armys sweep to victory was accompanied by a massive programme of ethnic cleansing as nearly 12 million Germans were expelled westwards. Two and a half million people in Western Europe were forced to return back east to thetender mercies of Stalin and his henchmen, mostly against their will, and some at gunpoint by the troops from the Western Allies.

This book takes a global view; the whole world was transformed after the Second World War, more profoundly, it can be argued, than after the First. That war destroyed empires which had lasted for centuries the Ottoman, the Romanov and the Habsburg. From 1945 the remaining old European empires, such as the British, were no longer sustainable, despite some doomed efforts by fading powers to cling on to former glories. Imperialism was no longer dynastic but ideological loyalty was demanded less to a king or emperor than to an idea, say MarxismLeninism. Some readers may be surprised that much of the story I tell here is centred on Europe. But that is where the Cold War, the clash of civilisations which continued for the following four decades, was sharpest, at least when it began. What happened in Germany and Eastern Europe, Britain and France, in 1946 was considered by the major players at the time to be of the utmost importance. If there were to be a new armed conflict and in 1946 it very much looked as though there might be the battleground was likely once again to be in the heartland of Europe. It seemed to me sensible, therefore, to centre the book in Europe, at the same time showing how events in 1946 were dramatically shaping the future of Asia and the Middle East.

One country emerged from the war much stronger. Alone among the chief protagonists in the conflict, mainland America was physically untouched. The overwhelming dominance of the US as the worlds economic, financial and military powerhouse dates from 1946. The war lifted America out of Depression. The contrast between Americas new wealth and the poverty of its enemies and allies was of profound importance in the aftermath of the war.

In much of Asia liberation is not exactly the right word for events following the surrender of Japan. The European empires attempted to reassert their dominion over their old colonies: theFrench in Indo-china, the Dutch in the East Indies, the British in Malaya and Singapore, but they couldnt sustain traditional-style colonial rule for long. The agony of withdrawal was worse and more bloody for some than others humiliatingly for France in Vietnam for example. In the sub-continent, the British were desperate to leave as soon as they could; with indecent haste according to many critics, who argue that the British scuttled and caused the violence that accompanied the partition of India and Pakistan. It seems to me imperial folly to imagine that the British could have prevented the massacres, short of despatching hundreds of thousands of troops. Almost the only thing the Hindus and Muslims in India agreed on was that the British were the problem, not the solution.