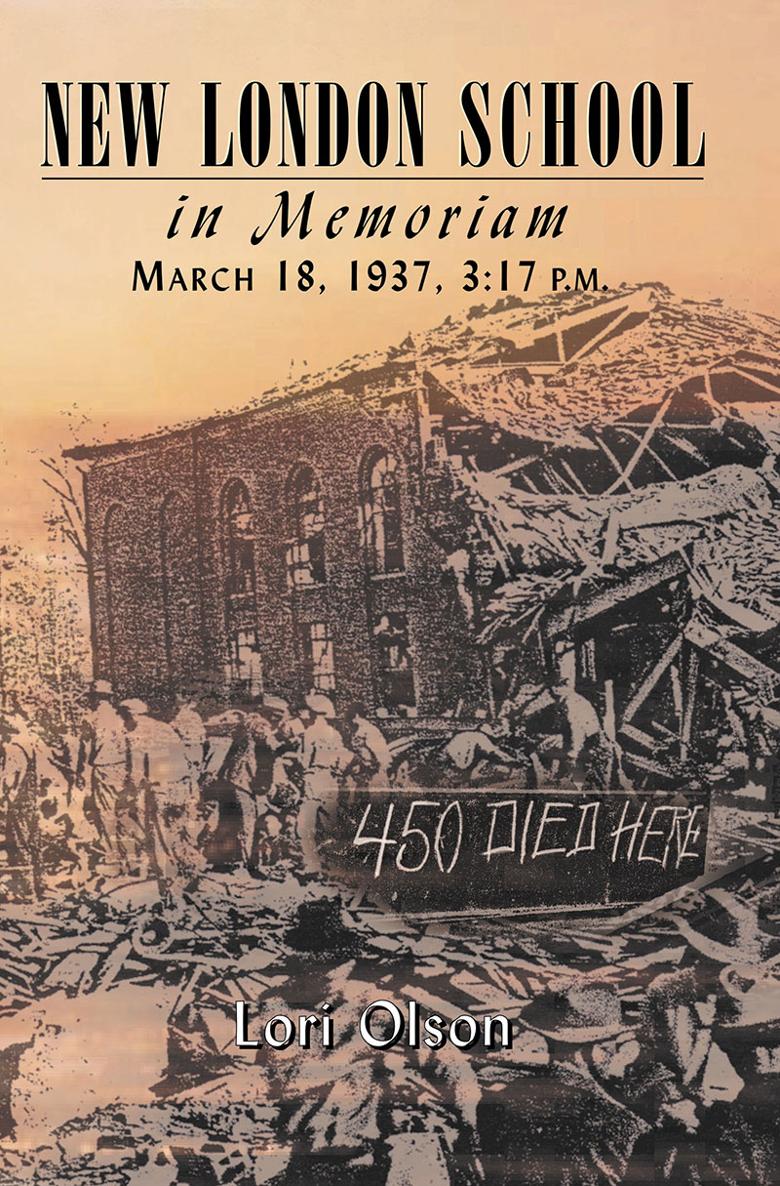

NEW LONDON SCHOOL

IN MEMORIAM

MARCH 18, 1937, 3:17 P.M.

Lori Olson

Photos courtesy of:

London Tea Room and Museum

Rusk County Historical Commission

London School Reunion Committee

| Copyright 2001 By Lori Olson Published By Eakin Press An Imprint of Wild Horse Media Group P.O. Box 331779 Fort Worth, Texas 76163 1-817-344-7036 www.EakinPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68179-203-3 Paperback ISBN 978-1-57168-438-7 |

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is not my story; it belongs to the people of Rusk County and New London, and the former students of London School. My first thanks must go to them. I thank them for their courage and strength and their willingness to share their stories and their lives with a stranger from Minnesota. Mollie Sealy Ward and all the folks at the London Museum and Tea Room were fantastic, giving me access to their vast knowledge, personal recollections, and storehouse of information and memories, as well as the their collection of Americana Histories videotapes. Thanks.

Thanks also to the research librarians and their respective staffs at both the Center for American History on the University of Texas-Austin campus and the Texas State Archives, also in Austin, and the supportive crew over at the Austin Hostel, my home-away-from-home during those long weeks of research. To Virginia Knapp at the Rusk County Historical Society in Henderson, thanks for spending the afternoon with me, providing me with a better understanding of the people and times, and allowing to me ask any question that came to mind.

Last but definitely not least, a heartfelt thanks to my daughter, Amanda, who was willing to follow her mother around the country looking for interesting people and stories and places without complaint, and who has literally listened to every word of this book, and to my parents for having the faith in me to let us leave. Thanks, thanks, thanks!

INTRODUCTION

What we keep in memory is ours unchanged forever

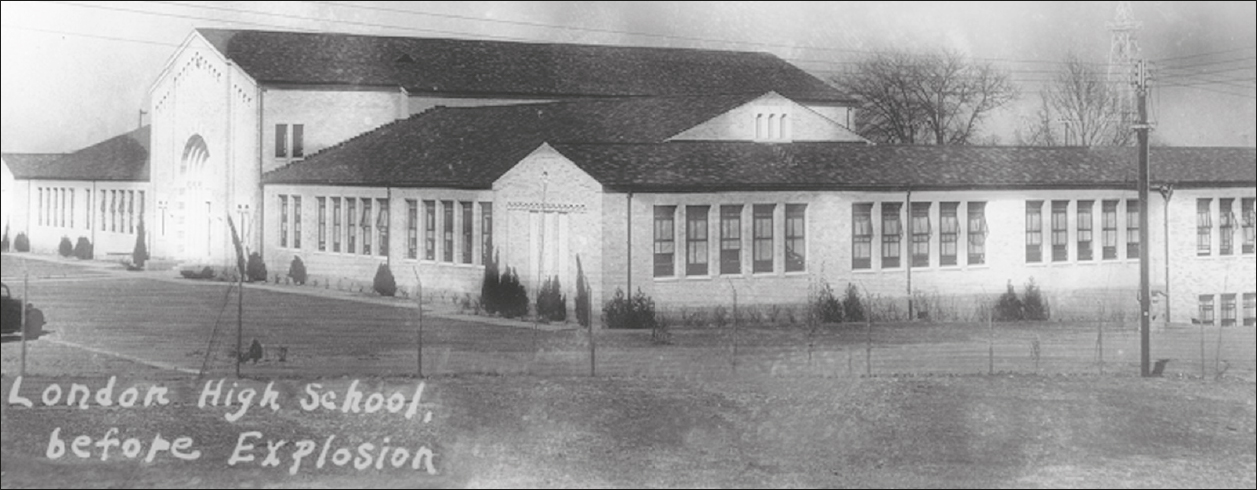

On March 18, 1937, a school exploded in the East Texas town of New London. It wasnt just any schoolit was London School, and since its construction in 1932, it had been touted as the richest school in America. For good reason. The school grounds were dotted with oil wells pumping up black gold, and the thirty-square-mile district to which the school belonged had an estimated assessed value in 1937 of more than sixteen million dollars.

The news media, though less plentiful in 1937, descended on New London after the horrible explosion, and attention-grabbing headlines appeared in newspapers across the United States and around the world. For days, readers were mesmerized by the horror, heartbreak, and heroism playing out in the tough-yet-tender community on the oil field. Messages of condolence were received from dignitaries and schoolchildren, and within weeks thousands of dollars had been contributed to erect some sort of memorial to the more than three hundred students, teachers, and visitors who had perished in the worst school disaster in American history.

Fear, outrage, and genuine concern brought to life by the explosion prompted legislators in Texas, and later throughout America, to enact school and public-building safety laws and regulations, and to require a malodorant be added to all natural-gas supplies. These were the disasters silver lining.

But, as happens, the media looked for new headlines to write, and the story of the London School explosion was all but forgotten outside of the close-knit community of New London. And, although not forgotten there, the stories were rarely told.

For literally a lifetime, the memories were silently pushed back, hidden behind a heavy curtain of shock and pain and guilt. In 1977 a few brave survivors reunited with former schoolmates and teachers to talk about the explosion that had changed their lives. For many, it was a turning pointthe first time in forty years that they had spoken of their childhood traumas.

While time and distance and silence had taken the cutting edges off all but the most painful memories, it had also caused other memories to be rewritten, to fade, and, sadly, to be lost from this world forever. Slowly and quietly, history was forgetting all that had happened in the oil fields of East Texas on March 18, 1937.

CHAPTER ONE

Mineral Blessings

Change was in the air in Rusk County, Texas, when wildcatter Marion Dad Joiner went hunting for black gold with Daisy Bradford No. 3. It was 1930, and the possibility that oil just might be found under the dry red dirt of East Texas provided the one glimmer of hope in what was the darkest night of the Great Depression.

Years later, soon-to-be oil magnate H. L. Hunt recalled that fateful day. I was at the well site on Friday, September 5, 1930, when the drill stem test was run on the Joiner well. When the tool was run in the hole and opened, oil blew through the top of the derrick, and I was confident that the well would be a producer. A month later, the wells casing was run and the well was swabbed. A rich column of oil shot over the top of the crown block on the derrick of Joiners Daisy Bradford No. 3. [It] turned out to be the Discovery Well of the great East Texas field. The drill stem test... did not cause the major oil companies to get very excited, but the greatest oil boom in history was on, whether or not we all recognized it at the moment.

Within days, unemployed men looking to prepare drill sites, build rigs and tanks, drill wells, and lay pipes in the richest oil field ever discovered had flocked to East Texas. On any given day, as many as four hundred of them might show up looking for work, and recently quiet Rusk County was quiet no more.

Private residences became temporary boarding houses, renting out beds and cots in any available space. Shotgun houses and tent cities with names like Turnertown and Sweeneyville sprang up seemingly overnight along the sides of gravel roads as the newly employed put down tentative roots. Service stations and cafeterias and food markets were quickly erected to provide basic necessities, and the gravel roads and two-wheel tracks leading out to the oil field became rush-hour highways clogged by bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Local landowners who would have been out picking cotton and attending to the fall harvest were instead waiting in line at the county courthouse in Henderson to cash in on the black bonanza. More than twelve hundred legal instruments pertaining to leases and royalties were filed with the county clerk during the first week of the boom alone, and it was estimated that within that same period, Rusk County people had received at least a half a million dollars as payment for leases and royalties.