First published in Great Britain in 1991 by

LEO COOPER

190 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JL

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

47 Church Street

Barnsley, S. Yorks S70 2AS.

Copyright John Frost 1991

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 0 852052 232 3

Typeset in 11/13pt Linotron Bembo by

Hewer Text Composition Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham PLC, Chatham, Kent

CONTENTS

I am very grateful Major-General Frost asked me to write a preface to this book about his life. It is the story of the life of a great soldier who does not hesitate to call a spade a spade.

I am particularly impressed by the last chapter and his description of the battle of Arnhem.

I only learned a few years ago that Montgomery had all the details about the German Panzer Division and had photographs of them taken by a Spitfire. I will never understand why he did not inform the gallant Airborne Forces about this.

When I asked his Chief of Staff, Freddie de Guingand, why Arnhem went wrong, he said: Its very simple, I was sick. Had he been there, I think the operation could have succeeded and the Netherlands would have been spared the Hunger-winter.

Prince of the Netherlands

INTRODUCTION

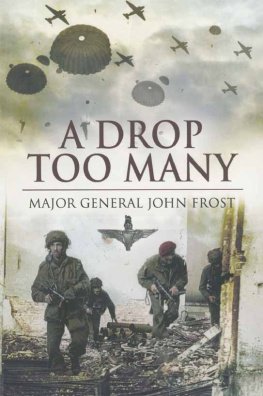

I started this book at the behest of my publisher who wanted me to record my life in the Army, other than my wartime experiences which I had previously described in A Drop Too Many.

After many vicissitudes it has become almost an autobiography. Rather difficult in many ways because the most important part of any professional soldiers life must be the wartime years when he is really put to the test. However, quite a lot seems to happen in peacetime and perhaps some of my experiences may be of interest. Most of the places in which I served are no longer available to todays soldiers, so perhaps it is useful to describe them.

Faced with the problem of a title for the book, I finally came up with Nearly There. Firstly, because at the age of 78 there cannot be all that more to come and, secondly, because although I achieved quite a lot, I never really hit the jackpot.

I owe much to Claire Attwater who did nearly all the typing and gave me encouragement when I was flagging, and give great credit to my wife who listened to the early drafts and finally took most diligent care over reading the proofs. Also to Captain Johnnie Coote who persuaded me to carry on when my first publisher packed up.

By far the best thing that happened to me was my marriage to Jean and it is to her that I dedicate this book.

JOHN FROST

Milland,

1991.

I WAS BORN IN POONA on 31 December, 1912. My father, who had begun his military service with the Yeomanry during the Boer War, subsequently being commissioned into the Cheshire Regiment, had transferred to the Supply and Transport Corps of the Indian Army. He had been one of twelve children and very little money could be spared to bolster his career so, when he fell in love and wanted to get married, the additional income from the transfer made sense.

The family had been ropemakers for three generations and lived in Epping Forest, my grandfather had married a Dutton, which family stemmed from Cheshire.

My sister, Betty, was born about one year after me and my mother brought us back to England just before the Kaisers War began. My father spent most of the war in France where he gained a certain amount of kudos for being involved with the development of ultra-light railways as a means of bringing ammunition and supplies to the forward positions. He was awarded an MC for one particular episode and mentioned in dispatches five times. I can just remember him when he came home from France on sporadic occasions. Towards the end of the war he was posted to Mesopotamia, as Iraq was then called, and as soon as it was possible my mother brought us children out to India, with the intention of going on to Mesopotamia as soon as that was practicable.

I remember little about India. Most of our time was spent up in the hills at Simla. A Swiss governess joined us there and travelled with us to Basra. By this time we had acquired a spaniel puppy. There seemed to be no difficulties in arranging for it to come everywhere with us, which was fortuitous, for during our one night in Basra our hotel was burnt to the ground and it was the spaniel that woke us all, thus allowing us to escape in time.

Our house on the west bank of the River Tigris outside Baghdad was fabulous to my young eyes. It was built round a courtyard and had a splendid garden to one side. The grounds spread to stables and tennis courts, beyond which was agricultural land irrigated by mechanical means from the river. There were great numbers of staff in the way of indoor servants, gardeners, grooms and drivers for cars, mostly Model T Fords, they being the only vehicles that could cope with the almost complete lack of roads. Perhaps most attractive of all the assets was the Sheerin, a motor-engined, Arab craft which my father had had altered to his own specifications with a wheelhouse, sleeping cabins and a saloon for his use on his many expeditions up and down the river. When he was not using it, we children and Mamselle could be wafted where we would.

It was amazing that any families had been allowed into the country at all, for in 1920 a full-scale Arab insurrection was taking place. Mesopotamia for many years had been a Turkish Province. The Turks had been harsh taskmasters and the inhabitants were not pleased at having to accept another power to govern them. Britain had been given a mandate over the country at the peace conference but a decision over their future rulers was still in abeyance. All the tribes were well armed with rifles, which had come into their possession as a result of disasters to each side during the war.

Up to three divisions of British and Indian troops were needed to keep order. Frequently, our own columns would be beleaguered by greatly superior numbers, while attacks on all forms of communications were commonplace. My father, in the rank of Brigadier, was the Director of Labour and, as such, he organized an armed labour corps, who were able to defend themselves and their projects most of the time. Anyway, it was not the sort of situation in which women and children could move about in safety, although we were blissfully unaware of what was going on until much later.

There were several horses in our stables. Up to this time I had never ridden but I was now mounted on what was thought to be a fairly gentle beast and sent off with one of the Arab grooms to learn the business. As he had no English and I no Arabic, the instruction was basic. It really only consisted of how to get on and off and to steer or stop by pulling on the reins. However, I suppose that one has a certain amount of inborn instinct in such things because I very soon felt confident and, though I had a few falls, before long I was out with the Exodus Hunt. This was a pack of salukis that had been formed by the 110th Company of the Corps soon after the end of the war Eck o Dus being Hindustani for their number. The salukis chased any jackal that could be put on the move in front of them, hunting entirely by sight, and the pace was tremendous. Old Turkish trenches and irrigation ditches provided the obstacles and were the cause of many an empty saddle. I little thought then that a few years later I should be the master of a pack of English foxhounds, which were to succeed the salukis in due course.

![Atkinson - An army at dawn: [the war in North Africa, 1942-1943]](/uploads/posts/book/178818/thumbs/atkinson-an-army-at-dawn-the-war-in-north.jpg)