Frontispiece

ARNHEM

1 Airborne Division

Major Ernest Watkins

Imprint

First published by the Army Bureau of Current Affairs 194445. This compilation published by Books Ulster in 2016.

Typographical arrangement Books Ulster

ISBN: 978-1-910375-46-4 (Paperback)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Table of Contents

Foreword

The British take great pride in heroic failure. Thus Arnhem is one of those episodes in twentieth-century British military history that takes its place alongside Gallipoli in 1915, the Somme on 1 July 1916 and Dunkirk in 1940. Although Churchill warned in the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk that wars are not won by evacuation, Dunkirk proved to be vital both psychologically and materially to the British war effort.

Arnhem, four years later, formed part of an operation code-named Market Garden, an ambitious two-part action in which three airborne divisions were to seize key bridges in the Netherlands, cross the Rhine, advance into Germany before the winter of 1944 and bring the war to an early conclusion. Market Garden was the brainchild of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, the victor of the second battle of El Alamein, and it required a greater level of risk-taking than one would associate with the normally careful and cautious Montgomery. Indeed, it was so completely out of character for him that Omar Bradley, his American colleague, observed in his memoirs published in 1961, Had the pious teetotaling Montgomery wobbled into SHAEF [Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces] with a hangover I could scarcely have been more astonished than I was with the daring adventure he proposed.

In War and Shadow (2002) General Sir David Fraser, Vice-Chief of the General Staff in the early 1970s, contended that Market Garden was a thoroughly bad idea, badly planned and only tragically redeemed by the outstanding courage of those who executed it.

The prolific military historian Max Hastings in All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-1945 (2011) claims that even had Montgomery secured a Rhine bridge, it is implausible that he could have exploited this to break through into Germany.

However, the late Richard Holmes, Professor of Military and Security Studies at Cranfield University and the Royal Military College of Science, in his Battlefields of the Second World War (2001), offers a radically different and more upbeat assessment:

While it was not done as well as it could have been, most involved judged it better to have tried and failed than to let the opportunity slip away. [Major-General] Roy Urqhuart [the commanding officer of the 1st Airborne Division] spoke for most when he concluded his after battle report with words: There is no doubt that all would willingly undertake another operation under similar conditions in the future. We have no regrets.

In his memoirs Montgomery stated, If the operation had been properly backed it would have succeeded in spite of my mistakes. Arnhem was his only military defeat.

The courage and endurance of the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem ranks high in the annals of the British army and constitutes one of the greatest feats of arms in the Second World War. Five British servicemen, four members of the Airborne force and one from the RAF, were awarded the Victoria Cross for their gallantry at Arnhem.

Arnhem Lift, the first book to be published about Arnhem, appeared as early as 1945. It was written by Louis Hagen, a Jewish refugee from Germany and a British army glider pilot who was present at the battle. However, it was the publication in 1974 of Cornelius Ryans book A Bridge Too Far that brought the Battle of Arnhem to the attention of a world-wide audience, followed by Richard Attenboroughs film of the same name three years later.

Gordon Lucy

WAR

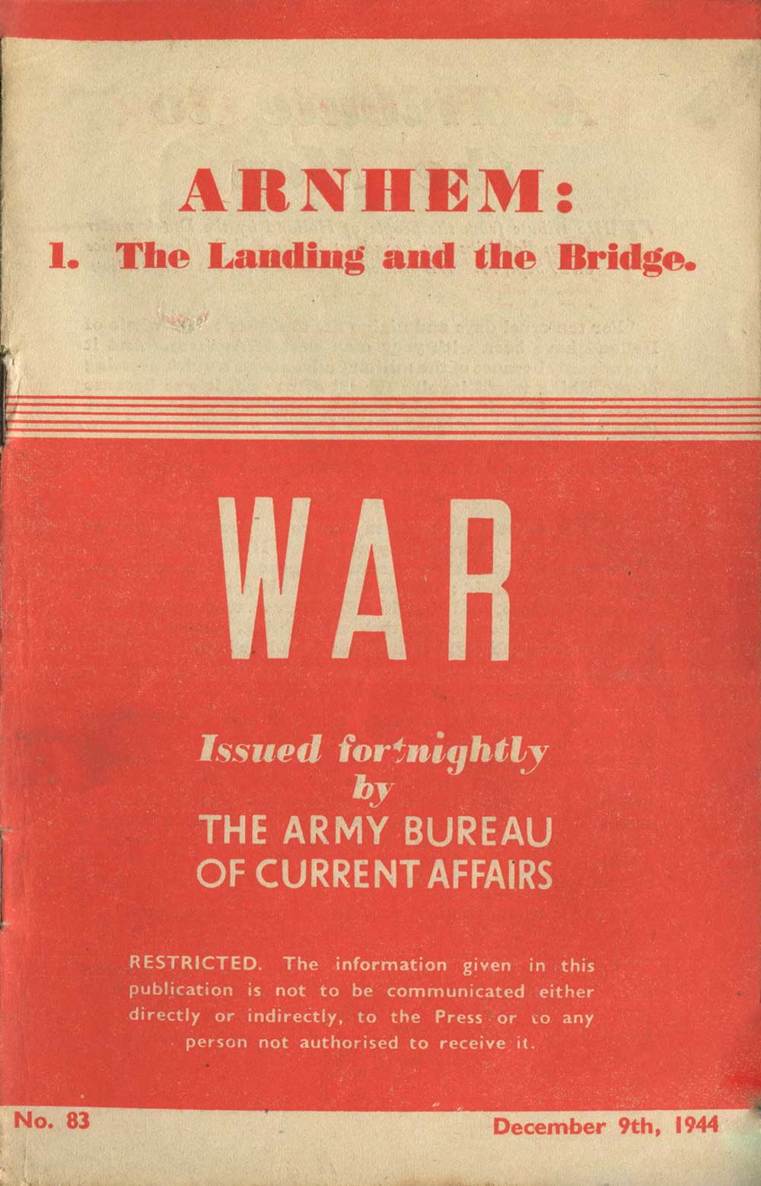

Arnhem: 1. The Landing and the Bridge

ABCA War Pamphlet No. 83, December 9th, 1944

A Tribute to the Men

THIS tribute from the people of Holland by the Dutch writer Johan Fabricius was broadcast in the B.B.C. Home Service on 27 Sep., 44. It is printed by permission of the Corporation.

For ten cruel days and nights the thoughts of the whole of Holland have been with your men west of Arnhem. And it was not only because of the military advantages a quick crossing of the Rhine would involve for all of usno, it was because of the men themselves, who were fighting in the heart of our little country for an ideal which is ours as well. We know what they must have been going through; we know what we owe them; we think of them as if they were our own boys.

This is what I want to say to you. Your men are no foreigners to us. Maybe they never saw Holland before they floated down over it on a sunny afternoon to liberate her people and the world; maybe they do not speak our language, not one of them, and find it difficult even to pronounce the names of the places where they are fighting, suffering, dying. But they are no foreigners in Holland, and we hope they realise that.

Some of these brave young men will stay behind in our country for ever. They shall not rest on cold foreign soil. The soil of Holland, which, in the course of our long and glorious history, received so many heroes for their eternal sleep, will proudly guard your dead as if they were the deeply mourned sons of our own people. The word heroes has been heard so often during this long and grim war that it is in danger of growing trite. But here it takes tangible shape, before the eyes of our people, who stand in awe and bare their heads.

That is what I wanted you, in this country, to know.

This is the operation of which the waiting period was described by Major Cotterell in

Airborne Attack

1 Airborne Div at Arnhem

By Major ERNEST WATKINS, R.A.

WAR Staff Writer

This account is not an official history of Arnhem. There are many gaps in the story, some of which can only be filled when men who are now prisoners return. It is a general account of the nature of the operation and of its course, based on narratives from some of the men who came back.

THE Siegfried Line is not an impassable barrier, but it is a considerable obstacle. Its major section extends from the Swiss frontier, just north of Basle, along the German frontier northwards as far as a point in the neighbourhood of Cleves, a few miles east of Arnhem.

The Rhine is also a considerable obstacle. This, too, runs from Basle northwards to the German-Dutch frontier just east of Arnhem, from where it flows west into the sea. Beyond it to the north there is no comparable barrier on the road into the Ruhr and Central Germany itself.

Arnhem is, therefore, a point of some importance.

Carrying the Road From Eindhoven

From the Escaut Canal, over which we had by 16 Sept. a small bridgehead, to Arnhem is 60 miles. There are two stepping stones on the way, Eindhoven (15 miles on), and Nijmegen (50 miles on). Eindhoven is a road centre, Nijmegen more important, in that it possesses a fine modern bridge over the Maas as it also flows west to the sea. Arnhem itself has two road bridges over its river, one, an old pontoon bridge, with a movable centre to allow the barge traffic of the Rhine to pass, the other a new and modern bridge of steel carrying northwards the road from Eindhoven and Nijmegen.