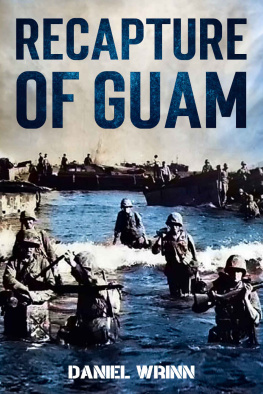

Liberation:

Marines in the Recapture of Guam

Table of Contents

by Cyril J. OBrien

With the instantaneous opening of a two-hour, ever-increasing bombardment by six battleships, nine cruisers, a host of destroyers and rocket ships, laying their wrath on the wrinkled black hills, rice paddies, cliffs, and caves that faced the attacking fleet on the west side of the island, Liberation Day for Guam began at 0530, 21 July 1944.

Fourteen-inch guns belching fire and thunder set spectacular blossoms of flame sprouting on the fields and hillsides inland. It was all very plain to see in the glow of star shells which illuminated the shore, the ships, and the troops who lined the rails of the transports and LSTs (Landing Ships, Tank) which brought the U.S. Marines and soldiers there.

The barrages, which at daylight would be enlarged by the strafing and bombing of carrier fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes, were the grand climax of 13 days (since 8 July) of unceasing prelanding softening-up. Indeed, carrier aircraft of Task Force 58 had been blasting Guam airfields since 11 June, while the first bombardment of the B-24s and B-25s of the Fifth, Seventh, and Thirteenth Air Forces fell as early as 6 May.

Up at 0230 to a by-now traditional Marine prelanding breakfast of steak and eggs, the assault troops, laden with fighting gear, sheathed bayonets protruding from their packs, hurried and waited, while the loudspeakers shouted Now hear this. Now hear this. Unit commanders on board the LSTs visited each of their men, checking gear, straightening packs, rendering an encouraging pat on a shoulder, and squaring away the queues going below to the well decks before boarding the LVTs (Landing Vehicles, Tracked).

Troops on the APAs (attack transports) went over the rail and down cargo nets to which theyweighed down with 40-pound packs as well as weaponsheld on for dear life, and into LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel). These troops would transfer from the landing craft to LVTs at the reefs edge, if all went as planned.

Aircraft went roaring in over mast tops and naval guns produced a continuous booming background noise. Climaxing it all was the voice of Major General Roy S. Geiger, commanding general of III Amphibious Corps, rasping from a bulkhead speaker:

You have been honored. The eyes of the nation watch you as you go into battle to liberate this former American bastion from the enemy. The honor which has been bestowed on you is a signal one. May the glorious traditions of the Marine Corps esprit de corps spur you to victory. You have been honored.

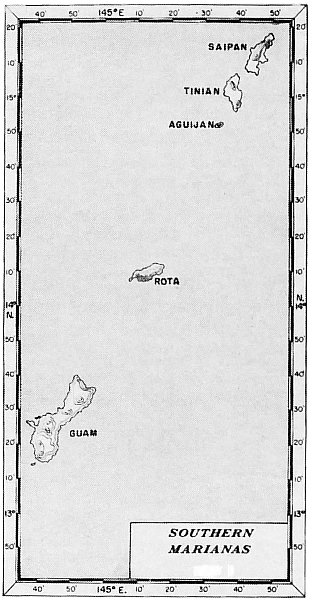

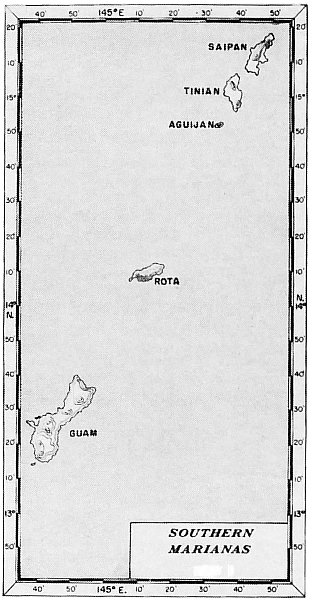

SOUTHERN MARIANAS

In the crowded, stifling well decks of the LSTs, the liberators climbed on board the LVTs and waited claustrophobic until the LST bow doors dropped and the tracked landing vehicles rattled out over these ramps into the swell of the sea. As the amphibian tractors circled (about 0615) near the line of departure, a flight of attack aircraft from the Wasp drowned out the whine of the amtrac engines and whirled up clouds of fire and dust, obscuring the landing beaches ahead. Eighty-five fighters, 65 bombers, and 53 torpedo planes executed a grass-cutting strafing and bombing sweep along all of the landing beaches from above the northern beaches of Agana, south for 14 miles to Bangi Point.

My aim is to get the troops ashore standing up, said Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly, Southern Attack Force (Task Force 53) commander, who earned the nickname Close-in Conolly during the Marshalls operations for his insistence on having his naval gunfire support ships firing from stations very close to the beaches.

Private First Class James G. Helt, a radioman with Headquarters and Service Company, 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, in the bow of an LVT moving towards shore, wondered, as did many others, if anything could still be alive on Guam? Ashore, Lieutenant Colonel Hideyuki Takeda, on the staff of the defending 29th Division, said the island could only be defended if the Americans did not land. In a diary, one Japanese officer noted that the only respite from the bombardment was a stiff drink.

The next best thing to a welcome mat for Marine assault waves had been laid by the audacious Navy Underwater Demolition Teams 3, 4, and 6, who cleared the beach obstacles. Navy Chief Petty Officer James R. Chittum of Team 3 noted that these pathfinders were usually close enough to draw small arms fire. At Asan, they exploded 640 wire obstacle cages filled with cemented coral, and at Agat they blew a 200-foot hole for unloading in the coral reef. Team 3, under Navy Reserve Lieutenant Thomas C. Crist, also removed half of a small freighter from a channel blocking the way of the Marines.

Swimmers as well as scouts, the demos reconnoitered right up on the landing beaches themselves. They left a sign for the first assault wave at Asan: Welcome MarinesUSO This Way.

At 0730 a flare was shot in the air above the waiting flotilla and Admiral Conolly commanded: Land the Landing Force. At 0808, the first wave of the 3d Marine Division broke the circle of waiting LVTs to form a line and cross the 2,000 yards of water to the 2,500-yard-wide beach between Asan and Adelup points. At 0829, the first elements of the 3d Marine Division were on Guam. Three minutes later, 0832, lead assault troops of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade crossed the shelled-pocked strand at Agat, six miles south of the Asan-Adelup beachhead.

[Sidebar ():]

General Roy S. Geiger

Table of Contents

Major General Roy S. Geiger, as the other general officers in the Guam invasion force, was a World War I veteran. He also was an early Marine Corps aviator. He was the fifth Marine to become a naval aviatorin 1917and the 49th in the naval service to obtain his wings. He went to France in July of that year and commanded a squadron of the First Marine Aviation Force. In the war and after, he saw service with Marine Corps air units. He also was well educated professionally, for he attended the Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in 19241925 and was a student in the Senior and Advanced Courses at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, 19391941. In August 1941, he became commanding general of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing and led it at Guadalcanal during the difficult days from September to November 1942. Back in Washington in 1943, he was Director of Aviation, until, on the untimely death of Major General Charles D. Barnett, Commanding General, I Marine Amphibious Corps, just prior to the Bougainville landings, General Geiger was rushed out to the Pacific to assume command and direct the landings at Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November 1943. He was the first Marine aviator to head as large a ground command as IMAC, which was redesignated III Amphibious Corps in April 1944. He led this organization in the liberation of Guam in July 1944, and in the landings on Peleliu on 15 September 1944. General Geiger led this corps into action for the fourth time as part of the Tenth Army in the invasion of Okinawa. Upon the death of Army Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner, Geiger took command of the Tenth Army, the first Marine to lead an army-sized force. In July 1945, at the end of the Okinawa operation, General Geiger assumed command of Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, at Pearl Harbor. In November 1946 he returned to Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, in Washington, and died the following year. By an act of Congress, he was posthumously promoted to the rank of general.