BEGINNINGS OF THE STEAM-ENGINE:

THE EARLY INVENTORS.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I.

Dawnings of Steam PowerThe Marquis of Worcester.

Table of Contents

When Matthew Boulton entered into partnership with James Watt, he gave up the ormolu business in which he had before been principally engaged. He had been accustomed to supply George III. with articles of this manufacture, but ceased to wait upon the King for orders after embarking in his new enterprise. Some time after, he appeared at the Royal Levee and was at once recognised by the King. Ha! Boulton, said he, it is long since we have seen you at Court. Pray, what business are you now engaged in? I am engaged, your Majesty, in the production of a commodity which is the desire of kings. And what is that? what is that? asked the King. Power , your Majesty, replied Boulton, who proceeded to give a description of the great uses to which the steam-engine was capable of being applied.

If the theory of James Mill[1] be true, that government is founded on the desire which exists among men to secure and enjoy the products of labour, by whatsoever means produced, probably the answer of Boulton to George III. was not far from correct. In the infancy of nations this desire manifested itself in the enforcement of labour by one class upon another, in the various forms of slavery and serfdom. To evade the more onerous and exhausting kinds of bodily toil, men were impelled to exercise their ingenuity in improving old tools and inventing new oneswhile, to increase production, they called the powers of nature to their aid. They tamed the horse, and made him their servant; they caught the winds as they blew, and the waters as they fell, and applied their powers to the driving of mills and machines of various kinds.

But there was a power greater by far than that of horses, wind, or watera power of which poets and philosophers had long dreamtcapable of being applied alike to the turning of mills, the raising of water, the rowing of ships, the driving of wheel-carriages, and the performance of labour in its severest forms. As early as the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon described this great new power in terms which, interpreted by the light of the present day, could only apply to the power of Steam. He anticipated that chariots may be made so as to be moved with incalculable force, without any beast drawing them, and that engines of navigation might be made without oarsmen, so that the greatest river and sea ships, with only one man to steer them, may sail swifter than if they were fully manned. But Bacon was a seer rather than an expounder, a philosophic poet rather than an inventor; and it was left to men of future times to find out the practical methods of applying the wonderful power which he had imagined and foretold.

The enormous power latent in water exposed to heat had long been known. Its discovery must have been almost contemporaneous with that of fire. The expansive force of steam would be obvious on setting the first partially-closed pipkin upon the fire. If closed, the lid would be blown off; and even if the vessel were of iron, it would soon burst with appalling force. Was it possible to render so furious and apparently unmanageable an agent, docile and tractable? Even in modern times, the explosive force of steam could only be compared to that of gunpowder; and it is a curious fact, that both De Hautefeuille and Papin proposed to employ gunpowder in preference to steam in driving a piston in a cylinder, considering it to be the more manageable power of the two.

Although it appears from the writings of the Greek physician, Hero, who flourished at Alexandria more than a century before Christ, that steam was well known to the ancients, it was employed by them merely as a toy, or as a means of exciting the wonder of the credulous. In his treatise on Pneumatics, Hero gives descriptions of various methods of employing steam or heated air for the purpose of producing apparently magical effects; from which we infer that the agency of heat was employed by the heathen priests in the performance of their rites. By one of the devices which he describes, water was apparently changed into wine; by another, the temple doors were opened by fire placed on the sacrificial altar; while by a third, the sacrificial vessel was so contrived as to flow only when the money of the votary was cast into it. Another ingenious device consisted in the method employed to pour out libations. Upon the altar-fire being kindled, the air in the interior became expanded and, pressing upon the surface of the liquid which it contained, forced it up a connecting-pipe, and so out of the sacrificial cup. The libation was made, and the people cried, A miracle! But Hero knew the trick, and explained the arrangement by which it was accomplished: it forms the subject of his eleventh theorem.

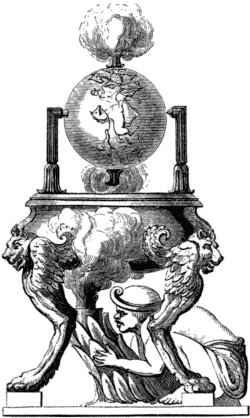

The most interesting of the other devices described by Hero is the whirling olipile, or ball of olus, which, though but a toy, possessed the properties of a true steam-engine, and was most probably the first ever invented. As Heros book professes to be, for the most part, but a collection of the devices handed down by former writers, and as he does not lay claim to its invention, it is probable the olipile may have been known long before his time. The machine consisted of a hollow globe of metal, moving on its axis, and communicating with a caldron of water placed underneath. The globe was provided with one or more tubes projecting from it, closed at the ends, but open on one side. When a fire was lit under the caldron, and the steam was raised, it filled the globe, and, projecting itself against the air through the openings in the tubes, the reactive force thus produced caused the globe to spin round upon its axis as if it were animated from within by a living spirit.[2]

The mechanical means by which these various objects were accomplished, as explained by Hero, show that the ancients were acquainted with the ordinary expedients for communicating motion, such as the wheel and axle, spur-wheels, toothed pinions and sectors, the lever-beam, and other well-known expedients; while they also knew of the cylinder and piston, the three-way cock, slide-valves and valve-clacks,[3] and many other ingenious mechanical details which have been reinvented in modern times.

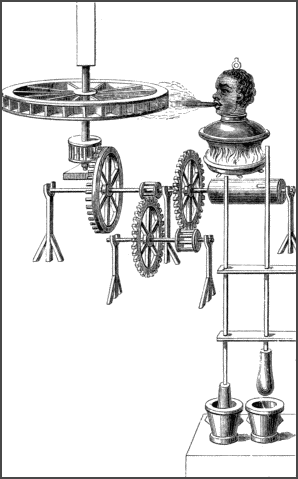

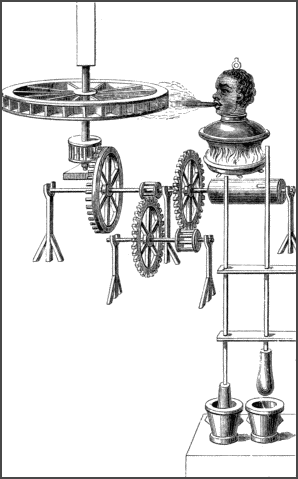

BRANCAS MACHINE.

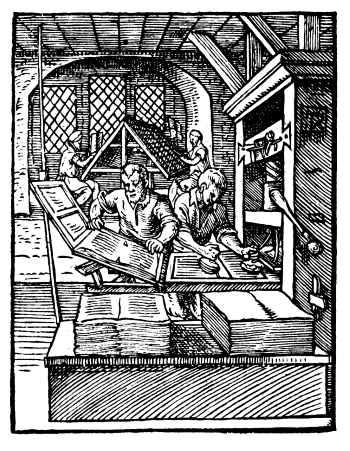

Heros book lay hidden in manuscript and buried in libraries, until the revival of learning in Italy in the sixteenth century, when a translation of it appeared at Bologna in 1547. By that time printing had been invented; and the multiplication of copies being thereby rendered easy, the book was soon brought under the notice of inquiring men throughout Europe. The work must, indeed, have excited an extraordinary degree of interest; in proof of which it may be mentioned that eight different editions, in different languages, were published within a century. The minds of the curious and the scientific were thus directed to the subject of steam as a motive power. But for a long time they never got beyond the idea of Heros olipile, though they endeavoured to apply the rotary motion produced by it in different ways. Thus, a German writer suggested that it should be used to turn spits, instead of turnspit dogs; and Branca, the Italian architect, used the steam jet projected from a brazen head to drive an apparatus contrived by him for pounding drugs. The jet forced round the vanes of a wheel, so as to produce a rotary motion, and this, being communicated to other wheels, set in motion a rod and stamper, after the manner shown in the preceding cut.