JAMES WATT

JAMES WATT

Making the World Anew

BEN RUSSELL

REAKTION BOOKS

Published in association with the Science Museum, London

For Lisa and Eli

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

In association with

Science Museum

Exhibition Road

London SW7 2DD, UK

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

First published 2014

Copyright SCMG Enterprises Ltd 2014

Science Museum SCMG

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234021

Contents

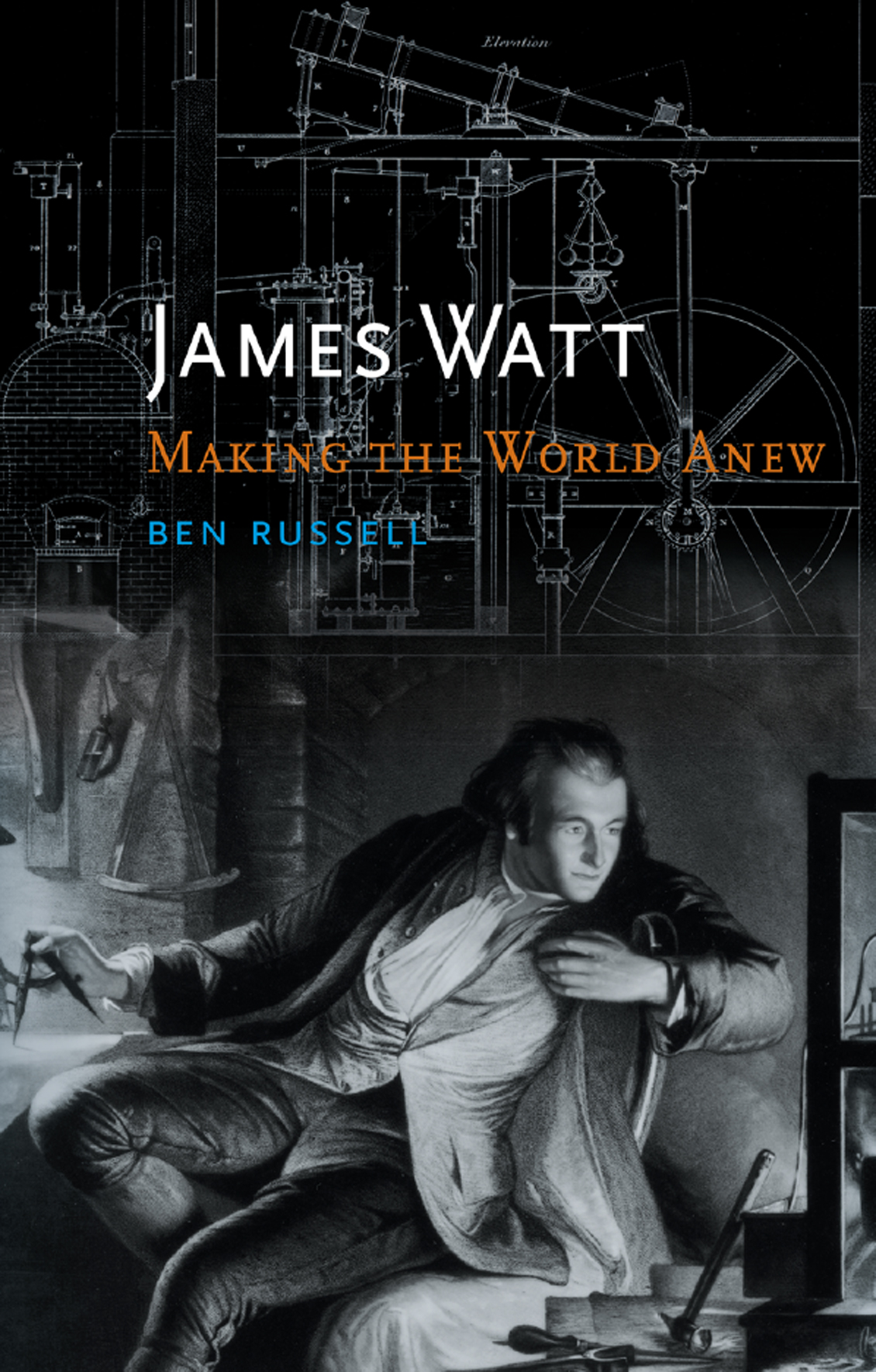

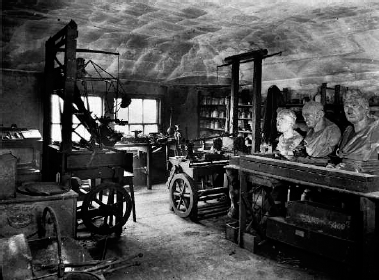

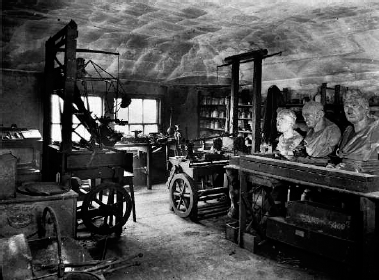

James Watts workshop at his Birmingham home, 1924, just before it was dismantled and moved to the Science Museum, London.

INTRODUCTION

Do We Want the Dust?

ON THE AFTERNOON OF 29 December 1924, Edward Collins stood alone, in a large, empty room at the top of a house on the edge of Birmingham. Outside the window, slates on the roofs of an adjoining wash house and dairy were beginning to slip, chimney pots leaned at odd angles, the trees were without leaves and a line of old lamp standards leaned against a wall from which the paint was flaking. The house had been uninhabited for four years and was about to be demolished.

Answering the question of why Collins felt obliged to collect the dust from the room and send it to the Science Museum in London requires some elaboration. The room in question was the workshop of the late engineer James Watt. It was on the top floor of Heathfield, the house he had built for his family in 1790, and Collins was the man responsible for looking after the property. Born in 1736 in Greenock, Scotland, and dying in 1819 in Birmingham, Watt is best known for his work on the steam engine, which became a symbol of Britains nineteenth-century industrial prowess, and he was the first engineer to be elevated into the pantheon of national heroes alongside soldiers and statesmen. He spent much of his time in the workshop after retiring from a long and fruitful career in 1800, and it contains a comprehensive physical record of the projects he undertook during that career. Upon his death in 1819, the workshop was locked up and preserved for 105 years. In 1924, Watts associations with steam power, and his by then long-standing position as a revered historical figure, saw the workshop acquired by the Science Museum in London and re-erected for public display. It was during the preparations for the latter that Collins wrote to the museum about the dust.

As it happens, the Science Museum decided against acquiring the dust. In February 1925, Collins again wrote to Henry Lyons, I also am sending... a parcel containing... all the small articles found by me in the dust swept up from floor of Room, nails out of walls, also 1/2 dozen of the nails used to fasten down floor boards, these are rather interesting. This is a little disappointing because, if the reader will forgive the slight stretching of a scientific point, the dust would have represented the DNA, not just of the steam engine, but of the many other projects that Watt worked on as well: plaster of Paris for copying sculptures, chemical substances of different types, iron filings and turnings, maybe bits of brass and glass from scientific instruments. The dust represented the multifaceted nature of Watts career.

The profusion of projects that Watt undertook is also reflected in the nature of the workshops larger objects. They dont only represent the man Thomas Carlyle described as Watt of the Steam engine... this man with blackened fingers, with grim brow... searching out, in his Workshop, the Fire-secret.for Watt as well as an active workspace. But above all, it is a shrine to making things.

This is a book about making things during Britains Industrial Revolution, covering the period roughly from 1760 until 1820. Broadly, it will look at the making of goods associated with Britains booming eighteenth-century industries, from scientific instruments and decorative metalware to cotton and pottery. Within those parameters, it will concentrate more particularly on the machine that became emblematic of Britains Industrial Revolution: the steam engine. The book will explore the extent to which the engine developed alongside, and depended upon, a range of handicraft practices honed in those other industries, and in other trades besides, from chemistry to blacksmithing and foundry work. The engine was as much a cultural machine as a scientific one, and the culture it emerged from was in large part one of making (and possessing) things, not just thinking about them. The major point to be made is that, over the period in question, the transition from making by hand to making by machine was slow, piecemeal and not a done deal: manufacture by machine remained a promise to be fulfilled long into the nineteenth century, not during the eighteenth. For this reason we might call this book a craft history of the Industrial Revolution, or a prehistory of engineering.

Recent surveys of the Industrial Revolution have emphasized the creation in Britain of a knowledge economy, which succeeded because it could generate useful knowledge and disseminate it to those who might exploit it commercially. In doing so, historians have created detailed theories of knowledge covering categories such as propositional and prescriptive know-how the former concerning phenomena identified in the natural world, and the latter concerning how things work. And the processes by which the former crossed over into the latter have also been analysed in detail: the historian Joel Mokyr has described them as the centrepiece of an Industrial Enlightenment.

Having the infrastructure to support the widest possible flow of ideas was no doubt important to Britains economy as it industrialized during the later eighteenth century. However, it seems counter-intuitive to place such a large emphasis on a single factor: On-the-job training produced skilled and knowledgeable men just as effectively as a more scholarly approach.

This is not to deny that scientific knowledge influenced how things were made. Science remained a potent force in making and manufacturing artefacts: the instruments that measured with increasing precision, the detailed understanding of chemistry that underpinned pottery and the evolving understanding of the internal workings of the steam engine, for example. However, we will attempt to move beyond abstract, theoretical science towards science that depended on physically carrying out experiments manipulating heat and materials, for example often in ways that were distinctly industrial in character. And we will also explore how science was just one of a number of factors that influenced how and why things were made.

First, however, we have to manoeuvre into a position from which we can see what those other factors could have been. The major The question arises: can we get inside their minds to establish what they knew about the processes of making?