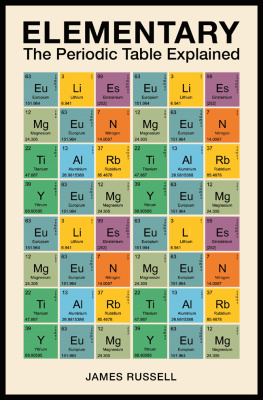

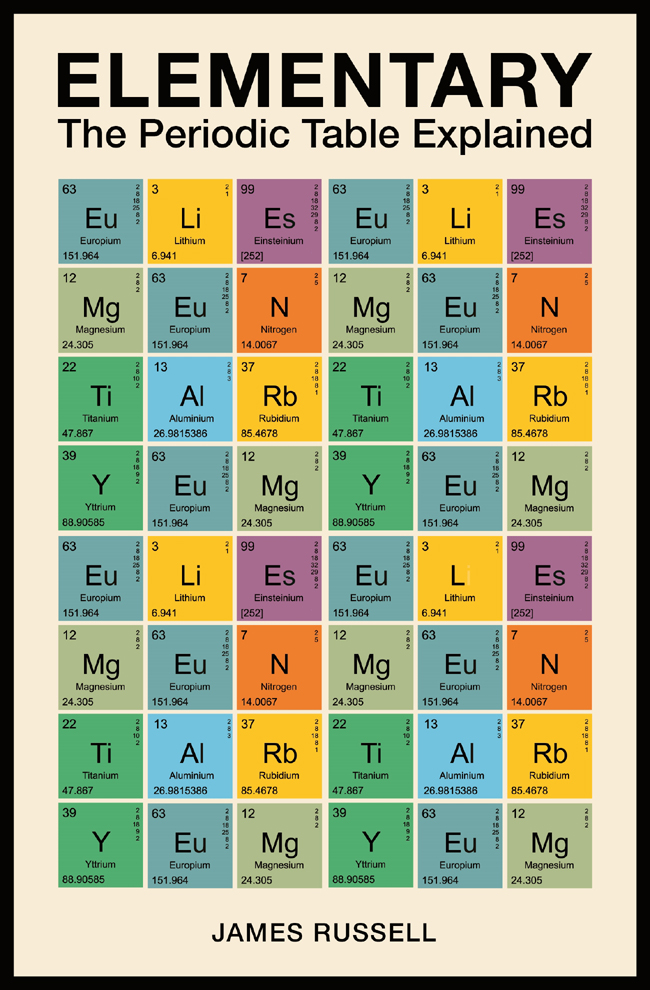

ELEMENTARY

ELEMENTARY

The Periodic Table Explained

JAMES M. RUSSELL

Michael OMara Books Limited

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2019

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-102-5 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-103-2 in ebook format

Cover design: Ana Bjezancevic

www.mombooks.com

Contents

T he periodic table is one of the most transformative scientific discoveries of the last two centuries, yet its inception required no scientific instruments or experiments just a pen, a piece of paper and a talented Russian chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev (18341907). In the early 1860s, fascinated by atomic theory the idea that elements are uniquely defined by their atomic make-up Mendeleev wanted to explore the idea of organizing all of the known elements in a simple diagram.

At the time, it was known that matter was made up of elements, sixty-two of which had been identified. Mendeleev started by arranging them in order of their atomic mass number, which is the total number of neutrons and protons in an atom of that element. (The nucleus of an atom is made up of protons and neutrons, around which a cloud of electrons orbits: the electrons are so light that their mass is ignored in calculating atomic mass.)

At first, he simply laid out the elements in a long row. However, the crucial insight came when he realized that within this row there were patterns: elements with similar properties were appearing at specific periods within it.

By cutting up the row and rearranging it in several shorter rows so that similar elements were above each other in columns, he came up with the first version of the periodic table. His left-hand column included sodium, lithium and potassium these are all solids at room temperature (which is usually taken to mean about 20C), they all tarnish easily and all react vigorously when mixed with water.

Mendeleev also came up with the periodic law, a summary of his insight that the elements fall into recurring groups, meaning that elements with similar properties occur at regular intervals. The qualities that constitute similar properties include their electronegativity, ionization energy, metallic character and reactivity of the elements.

As he continued to work on the table, which he first published in 1869, he occasionally tweaked the array, and found that the patterns were reinforced if he occasionally broke his own rules, by placing some elements out of order and leaving gaps. For instance, arsenic in the original table was in period 4 group 13, but Mendeleev believed it fitted more closely with the elements in group 15, so he moved it to that position, leaving groups 13 and 14 on that row empty.

The brilliance of this decision would later be vindicated when gallium and germanium were discovered; elements that fit perfectly into the empty spaces before arsenic. Over the following 150 years, more elements have been found or synthesized: argon, boron, neon, polonium, radon and many more besides. And each of these have been slotted into a spot on the periodic table, which currently contains 118 elements.

Mendeleevs rearrangement of the table was intuitive, based on the properties of the elements, but in his lifetime for more detail).

It is now well established that any element can be uniquely identified by its atomic number. But the number of neutrons is still significant, as it defines different isotopes. For instance, any atom with a single proton is a hydrogen, but while an ordinary atom of hydrogen has no neutrons (and can also be referred to as protium or 1H), there are two further naturally occurring isotopes: deuterium (2H), which has one proton and one neutron; and tritium (3H), which has one proton and two neutrons. And it is possible to synthesize further isotopes; if you bombard tritium with deuterium nuclei, you can make hydrogen-4 (4H), which has one proton and three neutrons. However, this is a highly unstable isotope, which will rapidly decay back into one of the naturally occurring isotopes.

Mendeleevs humble table not only predicted undiscovered substances: it also led chemists to a deeper understanding of atoms themselves. Chemists would eventually come to understand that the similarity in groups or columns of the periodic table was defined by the subatomic structure of the element. Electrons in an atom are arrayed in a number of levels, which are known as shells. Each of these has a limited number of spaces: the first level has just two spaces, then each of the next two levels has eight spaces.

As the atomic number increases, these spaces are gradually filled up. Elements in a particular group of the table have the same number of shells in their outer (or valence) shell and it is the number and arrangement of electrons in this shell that dictates how that atom will behave in a chemical reaction, in which different atoms exchange electrons and the molecules consisting of those atoms are transformed in the process. Elements that have a full outer shell (including the noble gases, which include helium, neon and argon) are more stable and less reactive, while elements with spaces on the outer shell are more reactive.

It is also important to know that the specific arrangement of the same number of electrons can lead to differences in the way that atoms of an element bond to each other; well see how different bonding structures of carbon lead to the quite different substances diamond, graphite and soot, which are known as allotropes of carbon.

So, our current understanding of the chemical structure of the universe is based firmly on Mendeleevs periodic table. Its use as a theoretical tool was one of the keys that unlocked the astonishing micro-world of subatomic particles. But this breakthrough was only made possible by the development of atomic theory, which had become widely accepted through the nineteenth century.

John Dalton was a gifted early nineteenth-century amateur scientist. He was a dissenter, so was barred from most British universities but was educated by the blind philosopher John Gough. After having to leave the radical New College in Manchester for financial reasons, he carried on with his own experiments and contributed significantly to our knowledge of weather prediction, how gases behave and colour blindness.

However, his most significant legacy was his statement of what came to be known as atomic theory. While pondering the fact that elements combine in predictable and regular ways with each other (for instance, compounds separate into definite proportions of their constituent elements), he came up with the first set of atomic weights. In 1810, he published a list of the atomic weights of hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulphur and phosphorus.

It was this insight that individual atoms of a given element are identical and have a definable mass that underpinned progress in chemistry in subsequent decades and led on to Mendeleevs periodic table.