30-SECOND

ELEMENTS

The 50 most significant elements, each explained in half a minute

Editor

Eric Scerri

Contributors

Hugh Aldersey-Williams

Philip Ball

Brian Clegg

John Emsley

Mark Leach

Jeffrey Moran

Eric Scerri

Andrea Sella

Philip Stewart

First published in the UK in 2013 by

Icon Books

Omnibus Business Centre

3941 North Road

London N7 9DP

email: info@iconbooks.net

www.iconbooks.net

2013 by Ivy Press Limited

The editor and contributors

have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form, or by any means, without

prior permission in writing from

the publisher.

This book was conceived,

designed and produced by

Ivy Press

210 High Street, Lewes,

East Sussex BN7 2NS, UK

www.ivypress.co.uk

Creative Director Peter Bridgewater

Publisher Jason Hook

Editorial Director Caroline Earle

Art Director Michael Whitehead

Project Editor Jamie Pumfrey

Designer Ginny Zeal

Illustrator Ivan Hissey

Glossaries Text Charles Phillips

Science Editor Sara Hulse

ISBN: 978-1-84831-616-4

Colour origination by

Ivy Press Reprographics

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Eric Scerri

Interest in the elements and the periodic table has never been greater. Of course, we were all exposed to the periodic table at some point in school chemistry. Everybody remembers the chart that hung on the wall of the chemistry lab or classroom parts of which we may even have been forced to learn by heart. The chart classifies all the known elements, those most fundamental components that make up the whole earth and, indeed, the whole universe as far as we know.

But perhaps we didnt appreciate at the time that the periodic table is without doubt one of the most important scientific discoveries ever made and is fundamental to our knowledge of chemistry today. The core idea is deceptively simple arrange the elements in order of increasing weight of their atoms and every so often we arrive at an element that shows chemical and physical similarities with a previous one. This doesnt just happen occasionally in the periodic table but is true of every single element except the very first few, which, of course, have no earlier counterparts in terms of atomic weight.

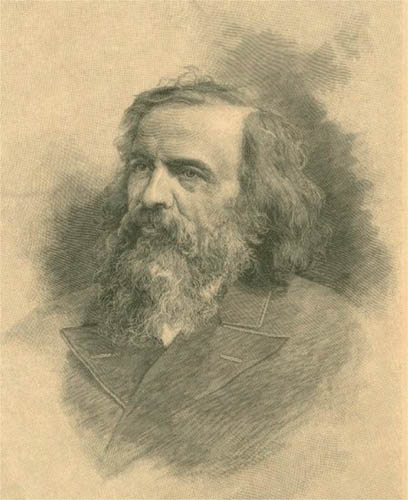

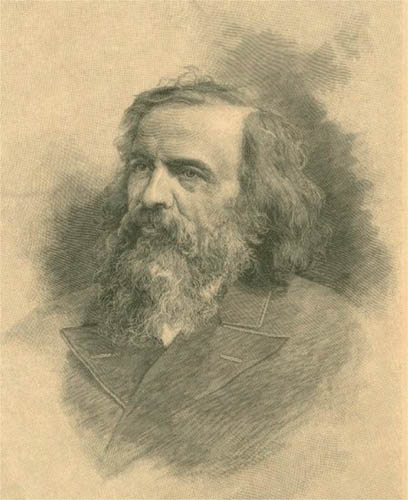

Dmitri Mendeleev

Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev was the first to propose the periodic table of elements as we know it now, as well as predicting the existence of some undiscovered elements. He is commonly referred to as the father of the peroidic table.

As a result of this behaviour, the linear sequence of elements can be arranged in a two-dimensional grid or table, much like a calendar that shows the recurring days of the week for certain dates in a given month. In this way, the tremendous variety among the elements is brought together into a coherent and interrelated form. Of course, these days we use atomic number (number of protons) to order the elements. But although this has solved a technical problem called pair reversals, it does not change the periodic table in any major fashion.

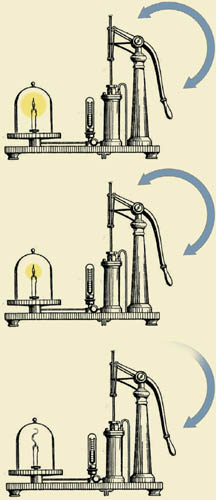

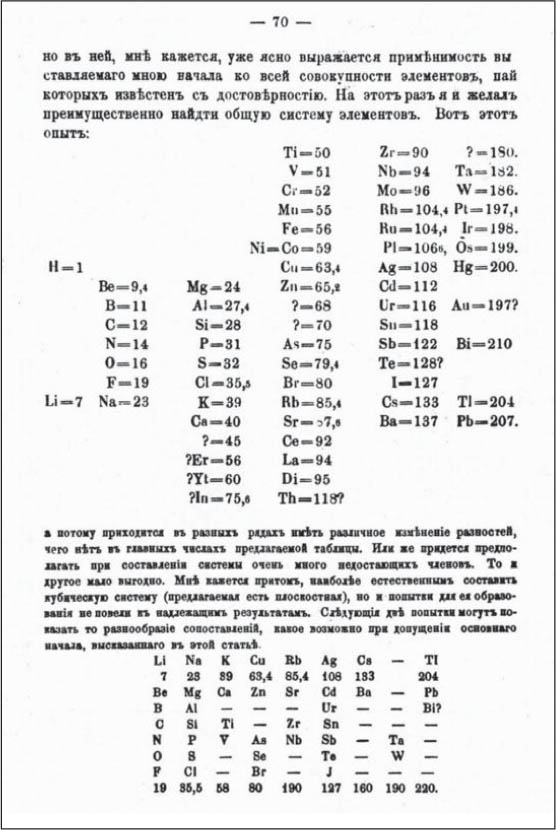

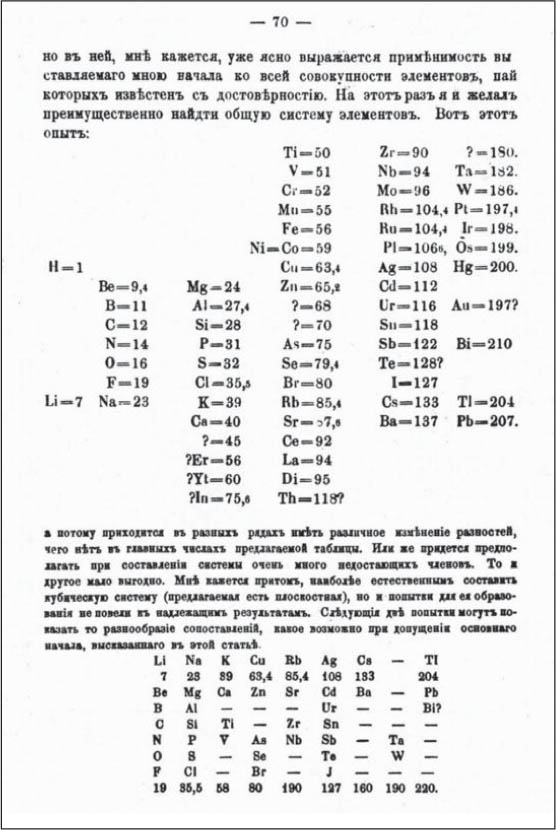

Mendeleevs table, 1871

Antoine Lavoisiers 1789 catalogue of elements formed the basis for the modern list, but it was not until Mendeleevs early arrangement in 1869 and final proposal in 1871 that the periodic table was born.

At the time Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev and a number of others discovered the periodic system, there was no underlying explanation, no apparent reason why the elements should hang together in this way. But the very fact that all the elements could be successfully accommodated into such an elegant system seemed to suggest deeper things to come. Mendeleev was able to use the periodic table to predict the existence of elements that had never been found before. Within about 15 years, three of his best-known predictions came to be. The discovery of gallium, scandium, and germanium solidified the notion that the periodic system had latched onto a deep truth about the relationship between the chemical elements.

Around the turn of the 20th century many physicists including J.J. Thomson, Niels Bohr and Wolfgang Pauli set about trying to understand what lies behind the periodic system. British physicist Thomson, the discoverer of the electron, was one of the first to suggest that the electrons in an atom are arranged in a specific manner that we now call an electronic configuration. Danish physicist Niels Bohr refined these configurations and provided what remains the gist of the explanation for why elements, in fact, repeat every so often, or to put it another way, why it is that certain elements fall into particular groups or vertical columns in the periodic table. Bohrs answer was that the elements in any vertical column share the same number of outer electrons, building on the emerging notion that chemical reactions are driven by outer electrons.

Next, Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli provided a further refinement to the notion of electronic configurations by suggesting that electrons have a hitherto unknown degree of freedom, which became known as spin. To put it in a nutshell, attempts to understand the periodic system contributed enormously to the development of quantum theory and these quantum ideas, in turn, provided a theoretical foundation for the periodic system of the elements.

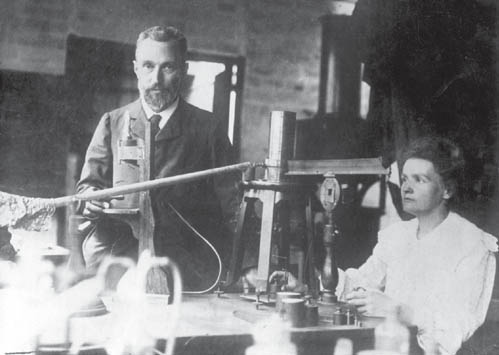

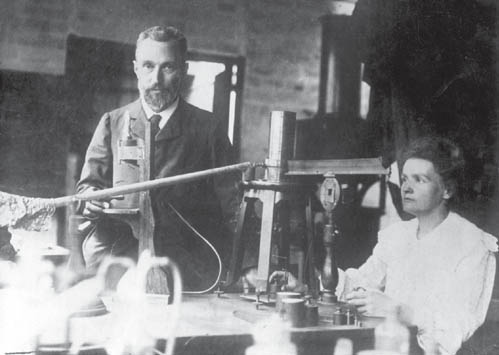

Radioactive research

Pierre and Marie Curie gave their lives in pursuit of discovery, living in poverty to fund their research. Their perilous study of the radioactive elements has since contributed to the understanding of modern nuclear physics.

This book will take you on a short and highly digestible tour of 50 of the best known, as well as most intriguing, elements in the periodic table. They range from soft metals, such as sodium, that can be cut with a knife, to the magnificent liquid metal called mercury, to the poisonous gas chlorine that was the worlds first chemical weapon.

Each episode is delivered in just 30 seconds and is presented by the worlds leading experts on the elements with a proven track record for successfully explaining science to a general audience. You will also learn about the historical figures connected with each of the elements, perhaps as the first to have extracted them or the first to think they had extracted them because there have been many, many dead ends and failed announcements of the discovery of a good number of the elements.

If condensing an account of each element to 30 seconds were not enough, you will also be provided with a 3-second summary plus a 3-minute version to ponder upon. You will read about the practical applications of the elements, their role in history and how they were first discovered. In some cases, you will read about the disputes that took place before they were eventually discovered or created in particle accelerators. You will learn how each element has its own unique personality, even though their atoms ultimately all boil down to different numbers of protons, neutrons and electrons. The chemistry of the elements essentially reduces to the physics of fundamental particles and yet something seems to defy complete reduction. Why else would the elements show such marked individuality while at the same time conforming to the basic physical laws imposed at the quantum mechanical level?

Next page