Dmitri Mendeleev

On the Relation of the Properties to the Atomic Weights of the Elements

[ Zeitschrift fr Chemie , 1869 , , 405 406]

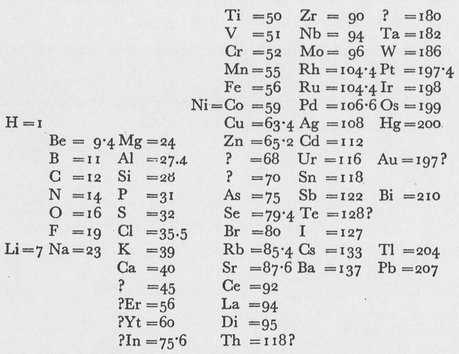

IF one arranges the elements in vertical columns according to increasing atomic weight, such that the horizontal rows contain analogous elements, also arranged according to increasing atomic weight, one obtains the following table, from which it is possible to derive a number of general deductions:

1. When arranged according to the magnitude of their atomic weights, the elements display a step-like [ stufenweise ] alteration in their properties.

2. The atomic weights of chemically analogous elements either have similar values (Pt, Ir, Os) or increase in a uniform fashion (K, Rb, Cs).

3. The arrangement according to atomic weight corresponds to the valencies of the elements and, to a certain degree, to differences in their chemical behavior, e.g., Li, Be, B, C, N, 0, F.

4. The elements most widely dispersed in nature have small atomic weights, and all such elements distinguish themselves by their sharply defined characters. They are therefore typical elements and, with justification, the lightest element, H, may be chosen as the typical standard.

5. The magnitude of the atomic weight determines the properties of the element; consequently in the study of compounds one must take into account not only the number and properties of the elements and their reciprocal interactions, but also the atomic weights of the elements. Thus the compounds of S and Te, Cl and I display many analogies, however conspicuous their differences.

6. It allows one to foresee the discovery many new elements, e.g., analogs of Si and Al with atomic weights between 65 and 75.

7. It is to be expected that some atomic weights will require correction, e.g., Te cannot have an atomic weight of 128, but rather one between 123 and 126.

8. The above table suggests new analogies between elements. Thus Bo(?) [U] appears as an analog of Bo and Al, which, as is well-known, has long been firmly established by experiment.

Dmitri Mendeleev

On the Correlation Between the Properties of the Elements and their Atomic Weights

[ Zhurnal Russkoe Fiziko-Khimicheskoe Obshchestvo , 1869 , , 60 77]

IN the course of the development of our science, the systematic classification of the elements has undergone manifold and repeated changes. The most common classification of the elements into metals and nonmetals is based on physical differences as they are observed in the simple substances, as well as upon differences in the character of the corresponding oxides and other compounds. However, what at first glance appeared to be unambiguous, lost its importance entirely when more detailed knowledge was obtained. Ever since it became known that an element, such as phosphorus, can exist in nonmetallic as well as in metallic form, it became impossible to base a classification on physical differences. Even the formation of basic and acidic oxides does not provide a reliable guide, since, between the definitely basic and definitely acidic oxides, there exists an entire series of transitional forms, among which must be included the oxides of bismuth, antimony, arsenic, gold, platinum, titanium, boron, tin, and many other elements. Moreover, the analogies between the compounds of such metals as bismuth, vanadium, antimony, and arsenic and those of such nonmetals as phosphorus and nitrogen, or between those of tellurium and the compounds of selenium and sulfur, or between those of silicon, titanium, and zirconium and the compounds of tin, no longer permit a distinction between metals and nonmetals for purposes of classifying the simple substances. The study of organometallic compounds, which has demonstrated that sulfur, phosphorus, and arsenic form compounds of the same kind as mercury, zinc, lead, and bismuth, conclusively confirms the validity of the above conclusion.

Likewise, those systems of simple substances based on behavior with respect to hydrogen and oxygen show many uncertainties and separate elements that, without doubt, exhibit great similarity. So far, bismuth has not been combined with hydrogen as have the elements similar to it. Nitrogen, which resembles phosphorus, forms extraordinarily unstable oxides and, in contrast to phosphorus, does not directly oxidize. Iodine and fluorine are clearly distinguished from each other by the fact that iodine readily forms compounds with oxygen but reacts with hydrogen only under extreme conditions, whereas fluorine has not yet been combined with oxygen (most often it displaces oxygen) but does form a very stable compound with hydrogen. Magnesium, zinc, and cadmium, which form such a natural group of simple substances, would also, according to this system, belong to different groups, as would copper and silver. On the same grounds, thallium would be separated from the related alkali metals, and lead from barium, strontium, and calcium. Even the simple substances forming the most natural of groups such as palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, on the one hand, and osmium, iridium, and platinum, on the other would be assigned to widely separated places in this system.

The ordering of the elements according to their electrochemical character is considered by the history of chemistry to be as unfortunate an attempt as is their ordering according to their relative affinities. Because of the diversity of the relations existing between the simple substances, one cannot think of representing their system in the form of a continuous series, since the mutual relations of the substances are extraordinarily diverse. If the substances are ordered according to their affinities or according to the electrical sequence, then one involuntarily leaves out of consideration the reversibility of reactions, which represents an essential property of chemical behavior. If zinc decomposes water (forming zinc oxide and releasing hydrogen), then hydrogen also decomposes zinc oxide. Chlorine displaces oxygen but oxygen does the same with chlorine, as we see from the synthesis of chlorine, for this reaction consists in the oxidation of hydrochloric acid. This fact is completely left out of consideration by those who desire to arrange the elements in a continuous series.

In recent times, the majority of chemists is inclined to achieve a correct ordering of the elements on the basis of their valency. In principle, this trend is very uncertain. This doctrine was called for by the investigation of organometallic compounds, by applying to them the law of paired atom numbers and the general concept of the limits of chemical compounds, and by the endeavor to circumvent the versatile theory of types. These relations have little or no application to the compounds of other elements. Nitrogen, for example, forms many compounds with unpaired atom numbers, as does mercury. Elements, such as vanadium, molybdenum, tungsten, manganese, chromium, uranium, arsenic, antimony, and the elements of the platinum group, form compounds with variable valencies which are so characteristic and which resemble so little the ideas we gain from an acquaintance with organic compounds that it is impossible, at least for the present, to think that we can make use of the strict concept of valency in order to understand the compounds of these elements. For aluminum, compounds which contain one atom of this element are totally unknown; for copper and mercury, the suboxides, in which these elements are monovalent, represent, in many regards, far more stable compounds than do the oxides. Thus, these elements similar to silver are monovalent elements with respect to the salts of their suboxides but, with respect to the salts of their oxides, they are divalent. Lead appears in its organometallic compounds as a tetravalent element, while its mineral compounds lead us to regard it as a divalent element. Iodine is a trivalent element in a certain sense, phosphorus is both tri- and pentavalent. For the determination of the valency of elements, one must come to a conclusion on the basis of the molecular composition of arbitrarily chosen compounds. If, for example, in the case of copper, cupric chloride is chosen as the saturated compound, then it appears that this saturated copper compound is a very unstable substance which easily changes into an unsaturated compound, namely cuprous chloride, in which copper is a monovalent element. But when one chooses the highest, albeit less stable, compounds as a measure for valency, then doubts regarding even the valency of hydrogen may arise thus hydrogen peroxide represents a compound of one atom of hydrogen with one atom of oxygen similar to cupric and mercuric oxide. In this event, arsenic, phosphorus, and nitrogen, antimony and others have to be regarded as pentavalent and even as heptavalent elements; iodine (because of its compounds with chlorine) must be regarded as a tri- or pentavalent element, and perhaps of even still higher valency. Then it is nearly impossible to determine the valency of elements such as manganese and aluminum. Potassium permanganate, which exhibits an analogy with potassium chlorate, is of such importance in the problem of valency that either manganese must appear as a monovalent element, like chlorine, or chlorine must be accepted as a di-, tetra-, or hexavalent element like manganese.