Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by Carl Swanson

All rights reserved

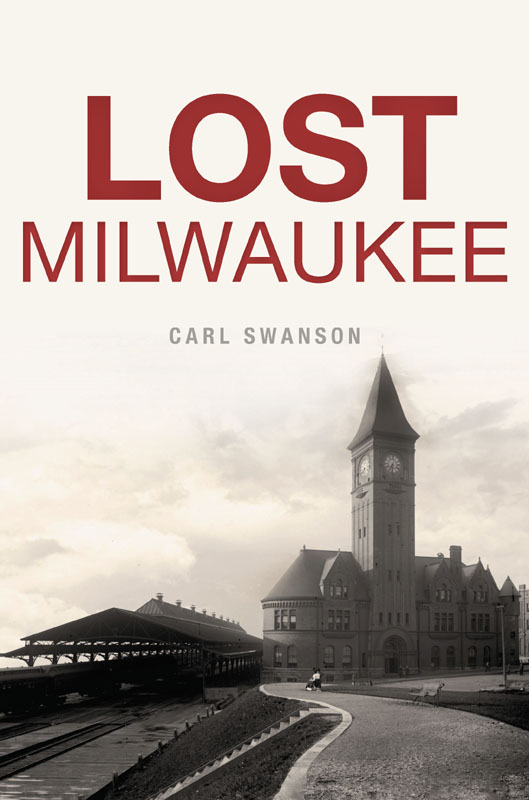

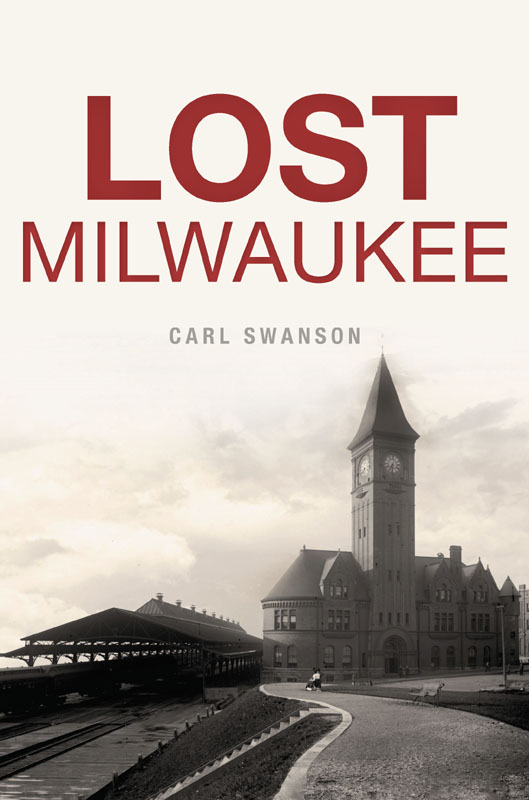

The cover photograph of Chicago & North Western Railways Lake Front Depot was captured around 1890. The elegant little station had unusual touches, including a bridal suite on its second floor with a view of the lake. The last train called on the depot in 1966. It was demolished two years later, becoming another example of lost Milwaukee. Courtesy of the Library of Congress/Detroit Publishing Company.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.459.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963239

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.863.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Judy

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It happened like this.

I came across a concrete foundation deep in the woods along the Milwaukee River not far from my home. Wondering what had once been there sent me on a search through the past, one that continues to this day. Along the way, I thought others would be interested in what Id learned, so I started a blog, MilwaukeeNotebook.com. More posts followed and became the book you are now holding.

That there is a book at all is largely due to John Rodrigue, commissioning editor at The History Press. John not only suggested the project, he provided the books overarching theme. Production editor Abigail Flemings careful and sensitive editing of the text is especially appreciated.

In particular, I thank Joseph Kmoch for his early interest in the project and his many helpful suggestions. My wife, Judy, and children, John, Daniel and Rachel, have been remarkably supportive throughout this project. Their presence in my life means more to me than I can express. John tracked down photographs and other information, much of it from the archives of the Milwaukee County Library and Milwaukee County Historical Society. The friendly assistance of the staff of these institutions, especially MCHS archivist Kevin Abing (author of the recent A Crowded Hour: Milwaukee during the Great War, 19171918 from Fonthill Media), is gratefully acknowledged.

Some of the chapters in this book are based on articles I contributed to the website OnMilwaukee.com and are reprinted by permission. I especially thank Bobby Tanzilo, managing editor of OnMilwaukee.com, for his enthusiastic support of my interest in local history. Bobbys Urban Spelunking series on that site and his book Hidden History of Milwaukee (The History Press, 2014) are essential reading.

Several individuals proposed topics or supplied information for Lost Milwaukee. Author and historian Thomas Fehring told me about the Briggs Loading Company, which is profiled in the Grenades and Underwear chapter. Thomas is the author of the superb The Magnificent Machines of Milwaukee and the Engineers Who Created Them, published in cooperation with the Milwaukee County Historical Society, as well as Whitefish Bay in the Images of America series and Historic Whitefish Bay: A Celebration of Architecture and Character, published by Arcadia Publishing/The History Press. Jeffrey Hoffman called my attention to the ruins of Evinrudes Milwaukee River outboard motor test facility. Dan Soiney suggested the chapter on Flambeau Motors, a much more obscure maker of outboard engines. Dan also provided his photograph of the Grand Theater.

Thanks are also due to the readers of MilwaukeeNotebook.com for their encouragement, additional facts and points of clarification for many of the topics covered in these pages. They include Ron Friedel, Lindsay Korst, Michael Gregoric, Thomas Manz, Marc Ponto, Gregory James, Matthew J. Prigge, Kathleen Wikoff and many others.

The Beer Line chapter is adapted from an article I originally wrote for the May 2004 issue of Riverwest Currents.

The stories in these pages are my retelling of events originally described in contemporary newspaper accounts, magazine articles, and published histories of the city. Ive credited my sources in the text and in the chapter notes. Any errors or omissions are mine. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs in this book were taken by me or are from my collection.

Lastly, I wish to thank those who have followed my blog and shared their love for Milwaukee. This book would not have been possible without their support, comments and suggestions.

INTRODUCTION

The Milwaukee River rises in Fond du Lac and Sheboygan Counties and flows about one hundred miles southward through farms and towns to join with two other rivers, the Menomonee and Kinnickinnic, in what was formerly a broad tamarack swamp surrounded by rolling hills on the shore of Lake Michigan and is now the city of Milwaukee.

The exact meaning of the Indian phrase that gave the river and city their names is debatable. Settler Joshua Hathaway said the name had been derived from the Potawatomi Main-a-wauk-ee seepe, which he translated as gathering place by the river. Hathaways version is the one generally accepted, although an early Indian language interpreter, Louis Moran, believed the name was from the Ojibwe Me-ne-waukee, meaning beautiful land.

James S. Buck, one of Milwaukees first European settlers and later the author of a four-volume history of the city, had this memory of his new home, which he first encountered when the area was still part of Michigan Territory.

This description will, I think, give a very correct idea of the appearance of Milwaukee in a state of nature. To say that it was simply beautiful does not express it; it was more than beautifulthose bluffs, so round and bold, covered with just sufficient timber to shade them well, and from whose

A scant handful of European settlers lived on the riverbanks when Buck arrived in 1836. The citys population had already reached 115,000 when he set down his recollections in the 1880s. Milwaukees pioneer days were even then an increasingly dim memory, as the fledgling city was entering a time of rapid expansion into one of the nations leading manufacturing centers. In many ways, its best years were still ahead.

Milwaukee residents would soon be able to board one of the steamboats providing regular service on the river between North Avenue and a popular beer garden on the west bank near Capitol Drive and a large amusement park on the east bank. On the way, they would pass immense multistory icehouses, a factory with one thousand men at work, a riverside bathhouse with throngs of swimmers and a strangely isolated river colony of homes. Today, all these have vanished, leaving hardly a trace behind.

In the following pages, we will revisit these places and many other examples, ranging from a high-speed rail line that became a bike path to a courthouse statue representing justice that locals thought resembled a drunken dancing girl.