Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by William E. Watson and J. Francis Watson

All rights reserved

Cover image: Painting depicting the burial of the first Duffys Cut victims by those who were still alive, painted by Fred Danziger for Sam Katzs Urban Trinity.

First published 2018

E-Book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.562.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018945791

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.908.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

Philip Duffy and Duffys Cut: An Immigrant Laborer

Becomes a Gentleman

Appendix A: Account of the Duffys Cut Incident

by Julian Sachse, 1889

Appendix B: Duffys Philadelphia and Columbia Mile 60 Contract,

Village Record, June 9, 1829

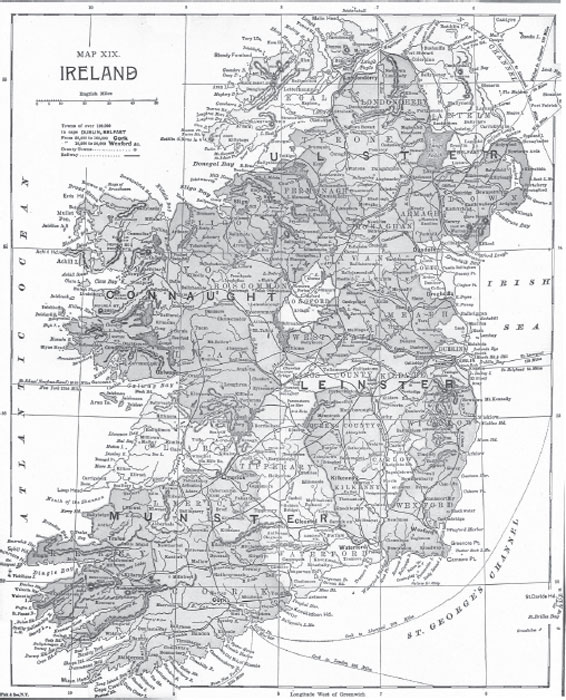

Map of Irelands provinces and counties. Nineteenth-century engraving. Watson Collection.

INTRODUCTION

This book was fifteen years in coming. The Duffys Cut Project began in 2002 as an effort to recover the remains of fifty-seven lost Irish immigrants to America and to recover and properly commemorate a forgotten episode of disease and bigotry in the shared histories of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and of the Province of Ulster. To date, no full accounting has been made of the efforts involved in the recovery of that lost history, although the project has attracted a great deal of attention in the United States and in Ireland. It is a story that has touched the Irish and Irish American communities because of lives cut short at such a young age and the fact that it is literally the tip of the iceberg of dozens, if not hundreds, of sites like it dotting the landscape of the Industrial Revolution across the United States.

Perhaps twenty thousand Irish immigrants died building the industrial infrastructure of the United States in the nineteenth century, and for most of those men and women, their identities and sacrifices will remain unknown due to intentional lacunae in the sources. For the fifty-seven who died at Duffys Cut, a series of remarkable coincidences resulted in the recovery and reburial of at least some of them in proper graves in the United States and in Ireland. The Duffys Cut Project team and Immaculata University student dig crew labored for more than a decade at the site to make sure that some of these common laborers would not remain anonymous.

This book is dedicated by the authors to Joseph F. Tripician, their maternal grandfather, who was a Sicilian immigrant railroader and who started out as a stonemason and eventually became executive assistant to the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad and retired as that companys director of personnel. He instilled an interest in history in us and preserved the railroads file on Duffys Cut so that this history could be recovered.

IRELAND AND AMERICA

IMMIGRATION AND INDUSTRIALIZATION

IRELANDS TRAGEDY AND EXODUS

By 1832, Ireland had been under British rule for more than half a millennium. The Norman invasion of 1169 fused Ireland together politically with England, an arrangement that lasted until 1921 for twenty-six counties and which still exists in the six counties that compose the United Kingdoms province of Northern Ireland. Despite the repressive Norman feudal policies that benefited a small elite of colonists in the Pale of Settlement in the eastern part of the island, Anglo-Norman elites gradually merged with Irish natives. The succeeding Plantagenet dynasty tried to maintain strict feudal overlordship on the island and keep the peoples apart in the Statute of Kilkenny (1365) by banning the Old English from intermarrying with the Irish or using the Celtic language, Irish dress and Brehon Law.

The Reformation added a sectarian dimension to preexisting tensions in Ireland in the mid-sixteenth century. The state-sponsored Anglican Church confiscated the native Catholic churches and required financial support from the Irish majority in the form of tithes. Racist, anti-Irish attitudes expressed by Edmund Spenser (15521599) in A View of the Present State of Ireland (1596) reflected contemporary English attitudes toward the Irish and justified exploitive colonial state policies of the Tudor and Stuart dynasties in Ireland. The colonial civilizing policy again suppressed the native Irish language, dress, Brehon Law and Catholic religion (derisively termed popery) and forbade intermarriages between the Irish and the old settler Anglo-Irish aristocracy.

The uprising of the native Ulster earls, supported by Spanish troops, in the Nine Years War (15941603) resulted in their defeat by the Tudor army and their flight to the European continent. The conquerors began the Ulster Plantation, the British colony in the north of Ireland in which Scots Lowlander and English settlers (Presbyterians and Anglicans) were imported to take over the lands of dispossessed Irish Catholics who were opposed to the regime. The conquerors also enacted the Penal Laws to break the resistance of the native Catholic Irish. Catholics were barred from government and military posts in Ireland (as were Calvinists). Irish men and women deemed to be in rebellion were exiled to the Americas and the Caribbean. The Irish Confederates uprising in the Eleven Years War (16411652) led to their defeat by the army of Oliver Cromwell (15991658) and the loss of a quarter of the native Irish population due to war, massacre, disease and famine. Thereafter, Catholics were barred from parliament, and the Catholic priesthood was exiled. The Tudors, Stuarts and Cromwellians all sought to eradicate the lingering power of Catholicism to unite the Irish natives.

Irish Catholics were second-class citizens in their native country for the next two centuries of the Protestant Ascendancy period in Ireland. The Catholic majority was governed, persecuted and marginalized by the Protestant minority. Catholic hopes for independence were raised in the Irish campaign of the deposed Catholic Stuart King James II (16331701) against the Protestant King William III of Orange (16501702), who was married to Jamess daughter. Catholic troops were recruited from the disaffected and disenfranchised majority to join the army of James II in 168990. Protestant forces held out and stopped Jamess troops at the Siege of Derry in 1689, and Williams army decisively defeated James about thirty miles north of Dublin at the Boyne River in 1690 in the largest and most important battle in Irish history.

Irish Protestants of various affiliations found common ground in the anti-Catholic Orange Order (named for William IIIs origins in Orange, the Netherlands), founded in 1795. Sectarian killings between Irish Catholics and Irish Protestants broke out in Counties Antrim, Down and Armagh in 1797, yet in 1798, Anglicans and Presbyterians joined with Catholics in the United Irishmen revolt that occurred under Anglican Theobald Wolfe Tone (17631798). The revolt failed despite French intervention, and in 1800, the Irish Parliament was dissolved in the Act of Union. Any pretense of Irish autonomy vanished.