First published 1998 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Virginia Blain, 1998

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 97039920

Typeset in Sabon by Manton Typesetters, 57 Eastfield Road, Louth, Lincolnshire, LN11 7AJ

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-61200-6 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-61204-4 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-429-45937-5 (ebk)

The Nineteenth Century General Editors Preface

The aim of this series is to reflect, develop and extend the great burgeoning of interest in the nineteenth century that has been an inevitable feature of recent decades, as that former epoch has come more sharply into focus as a locus for our understanding not only of the past but of the contours of our modernity. Though it is dedicated principally to the publication of original monographs and symposia in literature, history, cultural analysis, and associated fields, there will be a salient role for reprints of significant texts from, or about, the period. Our overarching policy is to address the spectrum of nineteenth-century studies without exception, achieving the widest scope in chronology, approach and range of concern. This, we believe, distinguishes our project from comparable ones, and means, for example, that in the relevant areas of scholarship we both recognize and cut innovatively across such parameters as those suggested by the designations Romantic and Victorian. We welcome new ideas, while valuing tradition. It is hoped that the world which predates yet so forcibly predicts and engages our own will emerge in parts, as a whole, and in the lively currents of debate and change that are so manifest an aspect of its intellectual, artistic and social landscape.

Vincent Newey

Joanne Shattock

University of Leicester

Correspondence with Robert Southey (extracts)

Early poems, 1820-30

From Ellen Fitzarthur, 1820

From The Widows Tale, 1822

The sea of life

From Solitary Hours, 1826

Autumn flowers

The night-smelling stock

Farewell to my friends

The broken bridge

There is a tongue in every leaf

I never cast a flower away

Rangers grave. March 1825

Abjuration

The mariners hymn

From Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, 1827

My old dog and I

From The Birth-day ... to Which are Added Occasional Verses, 1836

To the sweet-scented cyclamen

The hedgehog

Once upon a time

Occasional poems, 1831-33

The Cats Tail: Being the History of Childe Merlin. A Tale, 1831

Tales of the Factories, 1833

Verse autobiography, 1836

The Birth-day; a Poem, in Three Parts, 1836

Last poems, 1836-47

From Robin Hood: a Fragment, 1847

The murder glen

Wild flowers (extract)

Written in the fly-leaf of my fathers old copy of Izaac Waltons Complete Angler

The landing of the primrose

The young grey head (extract)

The evening walk (extract)

Thats what we are

Sonnets:

Unthinking youth! How prodigal thou art

Forgive, O Father! the infirmity

On, on upon our mortal course we go

To an old family portrait

We came together at lifes eventide

Prose writings

Thoughts on letter writing (extract)

Childhood (extract)

Beauty

Harmless Johnny

Broad Summerford (extract)

Andrew Cleaves (extract)

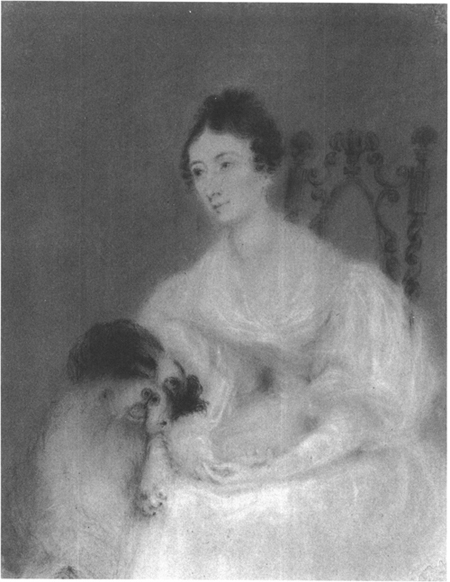

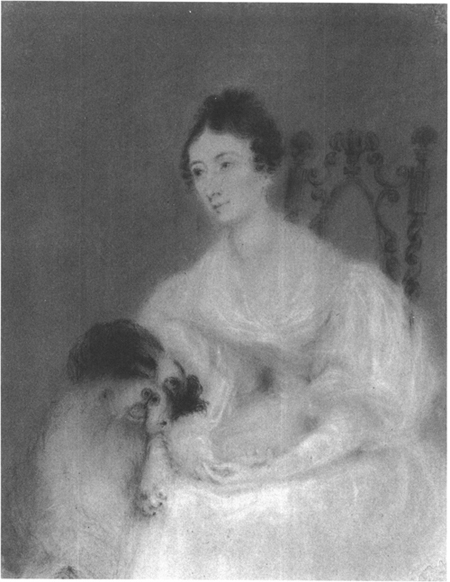

Frontispiece Caroline Bowles and Mufti. By herself.

To L. E. R.

I am a happy creature! none Im sure

Had ever friend so loving and so kind ...

Editha: a Dramatic Sketch

I first became interested in Caroline Bowles Southey in the 1980s when I came across her poem The Birth-day while working on material for The Feminist Companion. Here was a woman writing in the early nineteenth century, actually daring to present to the world the intimate story of her own childhood in the lofty Miltonic form of blank verse. What was even more startling, she was doing it with impressive ease and fluency well before Wordsworths supposedly unique composition in the genre, The Prelude, was posthumously published in 1850.

Some years later, in the autumn of 1994, I was in the Wordsworth Museum at Dove Cottage, Grasmere, and found myself by happy chance in a special exhibition of Romantic Women Writers in the downstairs space. To my surprise and delight, I found that no less than five pictures attributed to Caroline Bowles had been hung as part of the visual complement to displays of books and manuscripts. I had known that she had talent as an artist (her self-portrait was chosen by Ernest Dowden as frontispiece to his edition of The Correspondence of Robert Southey with Caroline Bowles), And Caroline Bowles was passionately fond of her dogs, who feature in a number of amusing (and some sad) poems. The second picture on display, a water-colour sketch of Edith Southey and Sara Coleridge, it has since been established, is actually by Edward Nash.

The next three paintings are landscapes in oils; one a view over Derwentwater, the other two of Greta Hall, for many years Southeys place of residence at Keswick in the Lake District. The first view of Greta Hall is of the entrance framed by heavily branched trees, showing a male figure dressed in eighteenth-century style. He carries what looks like a stout walking-stick: it may be Southey himself. The second view is much more intimate. It looks out from within Southeys study, over his desk and through the large window to the town and steeple beyond the grounds. I was struck by the contrast in the two pictures: the exterior scene quite formal, even a little forbidding in the way the trees are placed and the lone figure; the interior much more familiar, yet still in a sense expressing loneliness, looking outward from solitariness toward a wider life, yet cut off from it by the framing device of the window, curtained like a stage. (Both are reproduced in the current volume: see p. 26 and p. 218 below.)