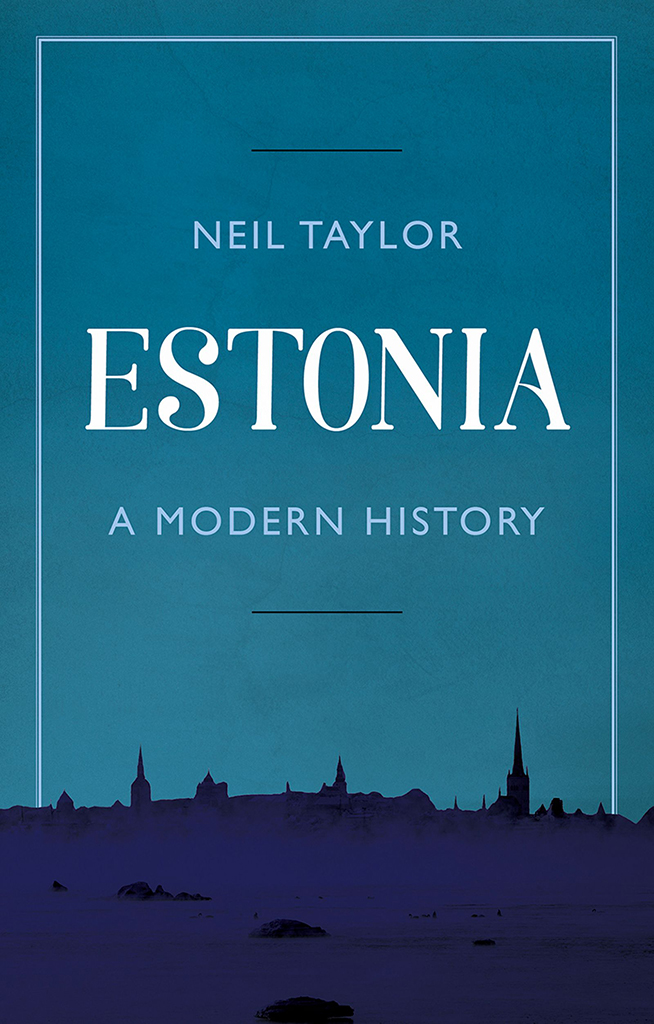

ESTONIA

NEIL TAYLOR

Estonia

A Modern History

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

41 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3PL

Neil Taylor, 2018

All rights reserved.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of Neil Taylor to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787381667

www.hurstpublishers.com

To my grandchildren Gustav, Iiris, Kristofer, Robin and Vivian, who will fortunately spend their whole lives in an Estonia very different from that endured by previous generations.

CONTENTS

The last history of Estonia to be published in Britain was that by John Hampden Jackson. It originally appeared in 1941, with a second edition in 1948. He wrote of the Russian occupation of which no-one can foresee the end, giving full details of what the Estonians were then facing. He would live until 1966 but wrote no more on Estonia, perhaps because he felt there was nothing more to say, as the Soviet system imposed itself there with ever greater determination. Travel by foreigners to Estonia was banned until 1960 and then was largely restricted to Tallinn. It is understandable that Hampden Jackson returned to French history, producing, among many other works, biographies of Georges Clemenceau and Jean Jaurs.

I am able to write about a completely different Estonia. In 1948, Tartu University was completely closed to foreigners, whereas in 2018 it was ranked by Times Higher Education as the best research-intensive university in New Europe. A few blocks of flats in the Tallinn suburbs, and an occasional abandoned headquarters of a collective farm in the countryside, perhaps with stables attached, are the only signs still visible of Soviet times. A strongly guarded and fortified border with Russia ensures that contact between the two countries is minimal. Younger Russian-speaking Estonian nationals are more likely to be seen working in London than touring St Petersburg. A generation of Estonians has grown up that speaks no Russian and similarly does not visit St Petersburg. Alliances with its other neighbours, through the EU and NATO, have strong support from the population, who can now take advantage of the Schengen regime to travel with only an identity card across the whole of Europe. These alliances help to ensure that Estonia remains free and that occupations will be an increasingly distant and irrelevant memory.

I have concentrated on the twentieth- and late nineteenth-century history to explain how Estonia has reached its current position. Estonians may be surprised at some of the people about whom I write at length, such as Viktor Kingissepp, the communist revolutionary, and Hjalmar Me, the most senior Estonian in the Nazi administration. Both tend to be written off in Estonian books as traitors, but they deserve greater analysis. A similar process has begun to take place in France with Adrien Marquet in Bordeaux and in China with Wang Jingwei in Nanjing, who both schemed successfully with their respective German and Japanese occupiers at the same time as Hjalmar Me in Tallinn. I also feel it is important to cover the Estonian leaders during the Soviet occupation, some of whom were total sycophants and others who genuinely did their best under the fraught circumstances with which they were presented. Concerning the first period of independence, I have been more sympathetic than many to the pre-war leader Konstantin Pts, who has been denied a statue in front of the Parliament building in Tallinn, and has to make do with a tram named after him that runs to Kadriorg, where he had his residence and office.

Many people have taken a great interest in this book and were very generous with their time and thoughts. It is a matter of great sadness to me that Charles de Chassiron, British ambassador to Estonia from 1994 to 1997, who was the first to read much of this text, died in April 2018, so has not lived to see its publication. I well remember our first meeting in Tallinn in 1994, the first of very many. He introduced me to Lennart Meri, with whom I could share my enthusiasm for Saaremaa Island. Charles and I stayed in close touch and I equally will remember our last meeting in February 2018 when he came to London for the concert celebrating the hundredth anniversary of Estonian independence, which was attended by the prime minister, Jri Ratas.

I have been privileged in recent months to meet Trivimi Velliste, founder of the Estonian Heritage Society in 1987 and then foreign minister from 1992 to 1994, who was able to give me a lot of help with information on that transitional era.

My wife Tiina Randviir has had to live with this book almost as much as I have. I doubt if she would have chosen Hjalmar Mes autobiography or articles by Karl Vaino for her bedside reading, but she endured both on my behalf, and the book has benefited greatly from this. I am glad that she could juggle this work with her translations and with the very different needs of five grandchildren all under six years old.

My technological ineptitude must have been a great source of concern to my editor at Hurst, Lara Weisweiller-Wu, but she has borne this burden throughout the production of the book with great patience. My university colleague Richard Phillips has kindly read the text and saved me from many potential howlers, including one date 2,000 years astray. Tim Page has spotted many inconsistencies, which will now not see the light of day. For mistakes that remain, I am of course solely responsible.

I have normally used the Estonian names for all places within the country, even though, before independence after the First World War, German ones were more commonly used, so I have stuck to Tallinn rather than Reval and Tartu rather than Dorpat. In the case of St Petersburg, I have used the name current at the time of the events I describe, so Petrograd during the First World War and until Lenins death in 1924, Leningrad during the socialist period, and St Petersburg for the tsarist and contemporary eras. Dates are according to the Julian calendar until February 1918, and then according to the Gregorian one, already used in the rest of Europe.

Much of the book has to deal with savage fighting, brutal imprisonment, deportation and censorship. However, I do feel that a lighter touch is occasionally called for. I therefore have found space to cover nude bathing, brothel hunting by Graham Greene, a Lennart Meri press conference held outside a toilet and arguments over how to put Hitler into the Estonian genitive case. Humour has kept alive the human spirit in many dark environments, and we can be pleased that it is now out in the open, like so much else in Estonia.

| Fig. 1: | Town Hall chest with painting of Tallinn, c. 1688, artist unknown. Reproduced with kind permission of the City Museum, Tallinn. |

| Fig. 2: | Peter the Greats Cottage, Kadriorg Park, Tallinn, Mrt Bormeister, 1956. Reproduced with kind permission of the City Museum, Tallinn. Photo Jaan Knnap. |

| Fig. 3: | Wax models of Valga Mayor and Headmistress, Valga, c. 1910. Reproduced with kind permission of the Valga Museum. |