Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Barney Blalock

All rights reserved

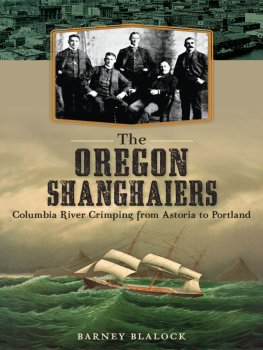

Front cover, bottom: Off Cape Horn, J. Latham & Co. 1877. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-01987. Inset: A Quintet of Boarding Masters, San Francisco Call, May 5, 1899. Top: Postcard from authors collection.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.967.0

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.430.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The Governor doubts Paddy Lynchs guilt for shanghaiing and pardons him, and tells him: Go thou, and shanghai no more. The penitentiary is no fit place for gentlemen who practice the gentle art of shanghaiing, for none such were ever sent there.

editorial comment, Oregonian, 1906

For Molly, Mary and John

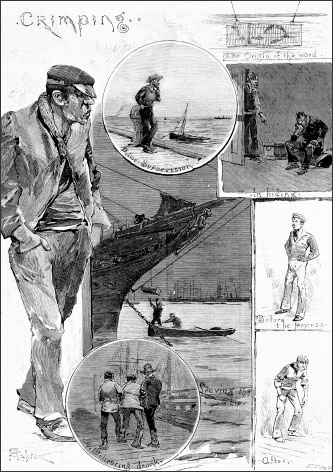

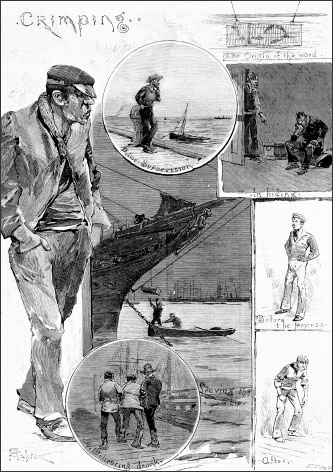

Crimps and Crimping, wood engraving by David Syme & Co. State Library of Victoria, picdb127911.

CONTENTS

Introduction

THE GENTLE ART OF SHIPPING SAILORS

From ancient times, vessels that sail upon the oceans have needed ways to assure that there would be sailors to follow the orders of the captain. Oftentimes, slaves were employed in the maritime servicemost notably, the galley slaves of the Romans. The British navy used press gangs to go into a neighborhood, where they would capture able-bodied men, enlisting them into His Majestys servicewhere to disobey the order of an officer could cause a man to be hanged. The men of these press gangs were called crimpsa word derived from the name of a device for trapping fish.

By the nineteenth century, the lot of the merchant sailor had improved to the point where floggings and other inhuman punishments were illegal. However, a sailor aboard a merchant vessel had no more rights than a member of the military for the duration of his contracted voyage. Once a mans name was signed on the ships articles, it was against the British maritime law, the laws governing the maritime trade of the United States and the laws of the state of Oregon for him to desert his ship until his contract was fulfilled. Even so, it was estimated that from the time Portland became a seaport until late in the first decade of the twentieth century, about three-fifths of all sailors deserted their ships, either in Astoria or in Portland. This was due to the sailors boardinghouse and shipping master system transferred to Portland from the older ports, such as San Francisco and New York.

Typically, except during intermittent times when the laws were being enforced, as a vessel came into Astoria (or Portland) after a long sea voyage, it was immediately boarded by a crimpeither a runner working for a boardinghouse or the boardinghouse master himself. The crimp, or his runner, would entice the sailors to stay at his boardinghouse on the tab, almost always promising a better ship with higher pay in the very near future. The sailors would not be paid until they completed their contracted voyage, so desertion meant that they lost their wages to the captain. The strongest impetus to desert was the fact that the men had been at sea for at least three months (usually much longer), were bored nearly to death and had not eaten decent food in many long weeks. In the sailors boardinghouse, they would be charged exorbitantly for everything from sleeping on a bed of hay to their daily food and drink, as well as any article they may have needed. By the time they were shipped by the boardinghouse master, they would owe him several months advanced wages. The money taken by the crimp was called blood money. Many is the sailor who went from port to port always in arrears, never having a farthing or a dime to call his own.

In Great Britain, a shipping master was a servant of the Crown. Not only did he assign sailors to ships, but he also saw them paid off, kept books on the wages contracted and paid and oversaw the examination of sailors to see how they should be rated. In the United States, a sailor on a British vessel (the great majority of the vessels were British in those days) was required to sign the ships articles in the presence of the British consul, vice-consul or his representative. If it was an American ship, he was required to sign in the presence of a United States shipping commissioner, or the collector of customs. The sailors were required to sign the ships articles of their own free will and to do so while sober. These regulations were to prevent men from being shanghaied or to sign while drunk or under the influence of drugs. In the United States, a shipping master was a title conferred on different sorts of men at different times and according to the custom of the port. They may have been men working for a shipping company or for a consortium of crimps, but they functioned as mediators or employment agents. In the case of there being no shipping master, the crimp acted as one himself; therefore the titles boarding master, boardinghouse master and shipping master are often used interchangeably in American newspapers. The news editors were also fond of using derogatory terms like land sharks, shanghaiers, blood-suckers, pirates, vermin or crimps whenever they felt the material warranted it. All of the crimps referred to their occupation as shipping sailors. The sailors themselves, however, often referred to these methods as shanghaiing, as a manner of speaking, even if they willingly signed the ships articles.

Commercial cargos from Portland were, for the most part, made up of sacked wheat from the Willamette Valley or sacked flour from the local mills and, to a lesser degree, canned salmon and lumber. Until the twentieth century, the vast majority of these cargoes were aboard British vessels, and nearly all cargoes en route to Europe were instructed to go to Queenstown for OrdersQueenstown being the port of Cork, in western Ireland. The harbor at Queenstown saw many hundreds of vessels each year, being the port where the shipping agents would receive the orders for the vessels final destination by telegraph from London or Liverpool. A cargo could be bought and sold several times while in route, depending on the speculations of capitalists. Until the Panama Canal was finished in 1914, all such shipments needed to go around Cape Horn, a distance of some eighteen thousand miles.

A sailor being picked to pieces by crimps. From Watts Phillips, Wild Tribes of London (London: Ward and Lock, 1855).

By the end of the 1880s, the ports of Astoria and Portland gained reputations as the worst in the world with regard to violence and dishonesty in dealings with sailors and captains. This reputation continued even after the evil was suppressed, but the crimping itself lasted for about three decades. This book is the true story of the men and women who shipped sailors. It is drawn from original source material, not from history books. The lack of factual information about these crimps available to the public has given rise to absurd legends, invented by writers of fiction. There would be nothing wrong in this at all, if some of these tall tales were not now purported as historical fact.

Next page