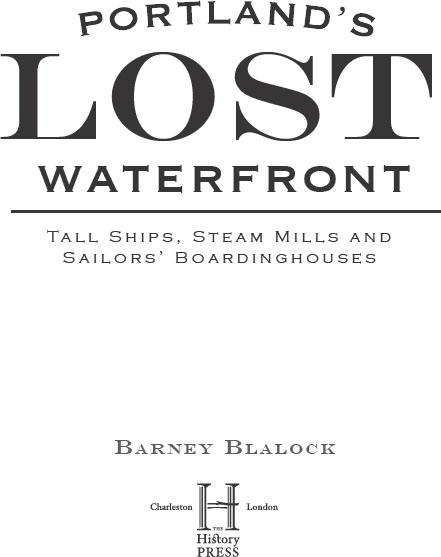

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2012 by Barney Blalock

All rights reserved

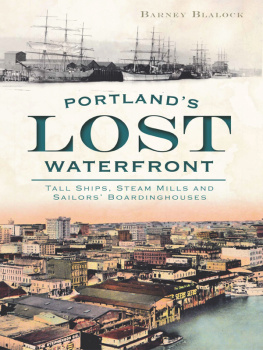

Front cover, top: Wheat fleet at Mersey dock. Late 1890s. Copyright Thomas Robinson.

Front cover, bottom: The rickety wharves of downtown Portland. Early 1900s. Postcard from authors collection.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.756.3

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print ISBN 978.1.60949.595.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Nektaria.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When I first started working on the grain docks of Portland, I found myself thrust into a bewildering world that stretched north along the river from the Steel Bridge in the center of town, to the grain elevators beyond the Saint Johns Bridge. This world revolved around the life and traditions of the Portland longshoremen, a group interesting enough to have once been the subject of an anthropology textbook. I worked alongside the longshoremeninspecting export grain for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)for over thirty-three years. During these years, my interest in the history of this place became something of an obsession. In these pages I hope to share some of the high points of my discoveries covering the period from the early beginnings of the city up to the First World War.

This is the story of a rough-sawn village, up 113 twisting miles of sandbar and snag-infested rivers, and how it grew to become one of Americas major seaports. We now sometimes hear the story that Captain John Couch declared Portland the end of navigation, and for this reason, it became a seaport, but the facts of the matter are far less cut and dried. It was a bold, and many said foolhardy, move to establish a seaport so far from the sea. For the first sixty years, there was no guarantee that the experiment would work, that all the dredging, jetty building and careful piloting would bring the maritime world to Portlands doorstep. It was a peculiar time in history when the West was an empty canvas, and the painters on that canvas were as slipshod and sundry a bunch as has ever congregated in one section of the globe.

The Portland waterfront was a particularly interesting place. Like the river itself, the waterfront was the source of the citys life. The money that trickled out from the banks into the hands of waiters, barbers, streetcar men, newsboys and the like largely came from grain deals worked out in London and Liverpool. The gas that burned in the lamps was made with coal from Newcastle. The gravel mixed with the cement of solid downtown buildings came from ballast dug from the quarries of Liverpool. The connection with Great Britain could be seen reflected in the names of some of the big grain docks themselves: Greenwich, Mersey, Victoria. Like Portlanders today, the town people cared little for the maritime business of the city, but when tall masts lined the wharves, they knew the grain fleet was in town. Then the saloons of the north end would hear the varied accents of the British tar. When things got breezy, and the whooping was particularly loud, it was most likely the Sons of Neptune interacting with the Riders of the Sagea state of affairs particularly unique to Portland.

This waterfrontwith its ferries and steamboats, stevedores and crimpsis all but lost from memory today. It is my ambition, in writing this book, to remedy that situation somewhat.

I would like to thank my dear wife, whose skills in all things related to English far surpass my own, and without whose help this book would resemble a dinner fed to canines. I would also like to thank Thomas Robinson for allowing me to explore his magnificent Historic Photo Archives (the closest I will ever get to being in a time machine).

My deep thanks to Molly Blalock-Koral for using her skills as a librarian to help me find some very obscure materials, to Mary Blalock for her enthusiasm and to John Blalock for his skills as a photographer. Finally, I would like to thank Darcy Mahan for her expertise and Aubrie Koenig for her initial encouragement and valuable help along the way.

For more information on the history of the Portland waterfront, the reader is encouraged to visit my website, www.portlandwaterfront.org.

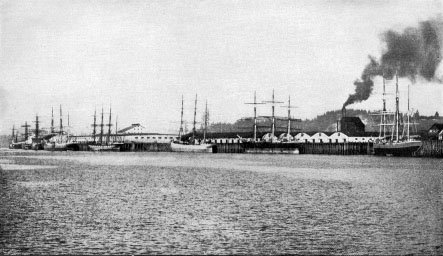

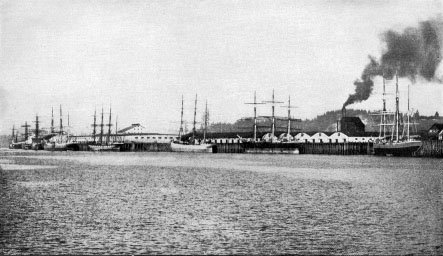

The Albina grain docks as they looked around 1900. Singer Sewing Machine Co. trade card.

CHAPTER 1

THE VILLAGE AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

On this sunset bound of the union, the tides of immigration meet. The East and West here pass each other, and here the ends of the earth are linked. This country represents the last conquest of man over nature. There is no farther West for him to subdue.

Elwood Evans, History of the Pacific Northwest, 1889

On the sunny morning of August 3, 1848, the schooner Honolulu arrived at the wharf in the new village of Portland, twelve miles north of the little town called Oregon City. A ship was a rare sight in this remote region. The few vessels that ventured up the Columbia usually went only as far as Fort Vancouver, the Hudsons Bay Companys regional headquarters. The previous year, the Oregon territorial government had established bar pilots in Astoria, but still few captains were willing to chance taking their vessels across a bar that U.S. Navy explorer Charles Wilkes called one of the most fearful sights that can meet the eye of a sailor. Once a ship was over the bar, within a few miles of Astoria, a large sandbar called the Hogs Back required even flat-bottomed steamboats to wait for the rising tide to pass. The other side of the Hogs Back, sandbars farther up the river and submerged snags from fallen giant fir trees threatened vessels at every bend.

In the Willamette valley, the energetic new farmers had come to find that there was no market equal to their efforts. Common goods necessary for a decent life were scarce or unavailable. The lumberyards were stocked full of lumber, the warehouses filled with grain and flour, but buyers were few, and prices offered were insultingly low. A letter printed in an Oregon City newspaper in 1846 stated that the community was without the absolute necessaries for the support of the most economical farming communitymany articles of clothing, and other articles absolutely necessary for our consumption, are not to be purchased in the country; our children are growing up in ignorance for want of school books to educate them, and there has not been a plow mould in the country for many months.

The Glenesslin, shipwrecked in 1913, shown in this dramatic picture of one of the victims of the Graveyard of the Pacific.

Next page