Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

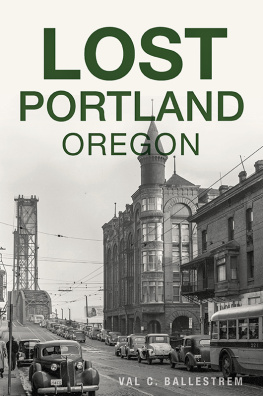

Copyright 2018 by Val C. Ballestrem

All rights reserved

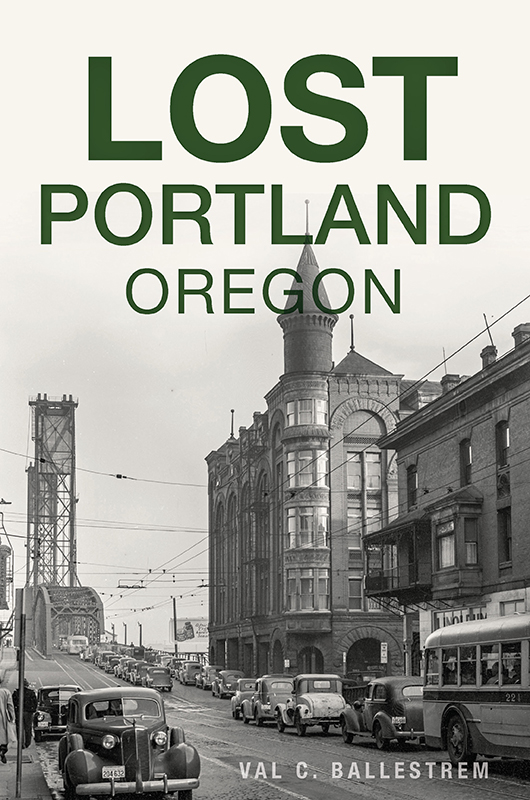

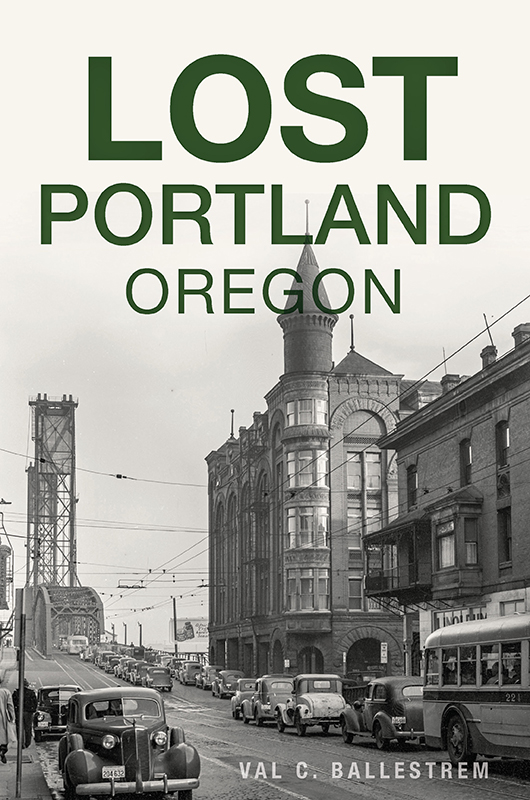

Front cover: Oregon Historical Society Research Library.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.593.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018952864

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.953.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Holli. Words cannot express how grateful I am for your never-ending encouragement and support of my work.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When I first considered writing a book on Lost Portland, I ran through a bunch of concepts as to what that meant. Lost what? People? Ideas? Longtime businesses? Sure, there are plenty of great examples of lost among all of these threads, but what about buildings or even neighborhoods? Portland has seen more than its fair share of such places lost, whether by design, neglect or accident. Many of these places have been gone so long that few people remember that they ever existed.

Thousands of structures have come and gone during the 150-plus years since Portland incorporated as a city. In developing the concept for this book, I decided to focus on aspects of Portlands built environment that, at least at the time of construction, were considered significant additions to the citys architectural landscape. This includes major commercial buildings, schools, houses of worship and a selection of architecturally interesting and historic houses, along with streetscapes and neighborhoods.

Through brief stories, I hope to exemplify how the city has physically changed over time and how old buildings are often held as a hindrance to progress. Temporary buildings and structures are not part of this story. Although lost aspects of the city, such as wartime housing, are replete with social, cultural and historical significance, they deserve a more thorough treatment than is possible in a book of this nature. Because the central city has always dominated the built landscape of Portland, most of the stories told herein take place on the west side of the Willamette River. For the east side of town, my goal was to include losses that represented major events, attitudes or changes in the city as a whole.

In deciding how to organize this collection of building stories, I took the advice of a colleague and friend who suggested I tell the stories in chronological order, by date of loss, rather than dividing them up thematically. The results, however arbitrary and imperfect, are five chapters that I feel are representative of the waves of architectural loss in Portland. In order to put these lost places in context with the Portland of the twenty-first century, I have used current street names and designations so that readers can better imagine what was once there.

As a firm believer in building conservation, I hope that this book prompts the reader to consider what we are losing today that should possibly be saved and, certainly, that should not be forgotten. As has happened throughout the United States, in Portland, we regularly and willfully destroy the hard work of our forebears. Is architectural loss a necessary part of progress? I would argue that it is a less than creative approach; it is neither socially, culturally or environmentally sustainable to continue erasing our physical past in the name of the future.

With that said, the loss of a building is not necessarily a bad thing. Some famous architectural losses in Portland have ultimately led to very good things. The beloved Portland Hotel was demolished more than sixty-five years ago and few Portlanders in 2018 ever stepped through its doors. However, with Pioneer Courthouse Square (built on the same property), it is safe to say the city eventually benefited from the loss of the hotel. At the same time, readers will note the significant number of losses in this book that resulted in not-so-positive outcomes. In 2018, is an eighty-plus-year-old surface parking lot in the heart of downtown really the best we can do?

This book is not a lament, although there are some very lamentable losses. I hope this book helps to broaden our understanding of how a city changes and how importantor at least interestingaspects of the past can get lost in the shuffle. As I write, new losses are taking place around the city while residents, special interests and officials struggle over the outcome. We can only hope that the new building causing a loss today will be the architectural landmark of tomorrow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In the summer of 2017, I heard that The History Press was looking for someone to write about lost Portland architecture, and the idea struck an immediate chord. For years, I had envisioned writing a book about Portlands past, and for once, the timing felt right. I had just curated an exhibit at the Architectural Heritage Center on essentially the same subject, so the concept was fresh in my mind. With encouragement from my wife and colleagues, I embarked on this fun and challenging journey.

The images in this book offer only a glimpse into some amazing Portland-area collections. The library and archives at the Architectural Heritage Center include a wonderful postcard collection along with the photography of George McMath and others. Access to this collection was key to making this book happen. I am forever grateful to Norm Gholston for sharing images from his private collection that include rarely seen views of the city. Thank you to Matt Cowen at the Oregon Historical Society for making its Minor White photographs from the late 1930s and early 40s available, and to Ken Hawkins for his insight and expertise into this collection. Tom Robinson, the Portland Archives and Records Center, Oregon Health and Science University Historical Collections and Archives, and Ed Teague at the University of Oregon Libraries also provided images, as did my colleague at the AHC, Doug Magedanz. Thank you all for helping to make this book possible.

I am also grateful to the many friends and colleagues who provided advice and support for this project, including Morgen Young, Amy Platt, Maija Anderson and the gang from the Ben Holladay Society, including Alexander, Dan, John and Tim. Lastly, I should thank Clio the cat for her constant attention while I spent countless hours writing and researching.

18951917

Expansion and Collapse

The earliest permanent white settlement buildings in Portland dated to the 1840s, but by the 1890s, little remained. The city had endured booms, busts, floods and fires. During this period, some older buildings found themselves physically relocated and repurposed, such as the Captain Nathaniel Crosby House, built around 1847 and long purported to be the first frame house erected in the city. The Crosby House originally stood near the Willamette River on Southwest Washington Street, but by the time of its demolition, around 1910, it stood near Southwest Fourth Avenue and Yamhill Street, serving as a commercial storefront.

Between the 1890s and the United States entry into World War I in 1917, several prominent Portland buildings were erected and lost. It was a period in Portlands history with an inordinate amount of short-lived buildings. Some were simply outgrown and replaced, but there was also at least one epic building failure. The gradual expansion of the city to the west, away from the flood-prone Willamette, erased residential areas once at the outskirts of town, replacing them with substantial new commercial buildings. Fire played a significant role in the loss of buildings, much as it always had, but the biggest impact was the result of a growing city leaving many buildings in untenable locations.

Next page