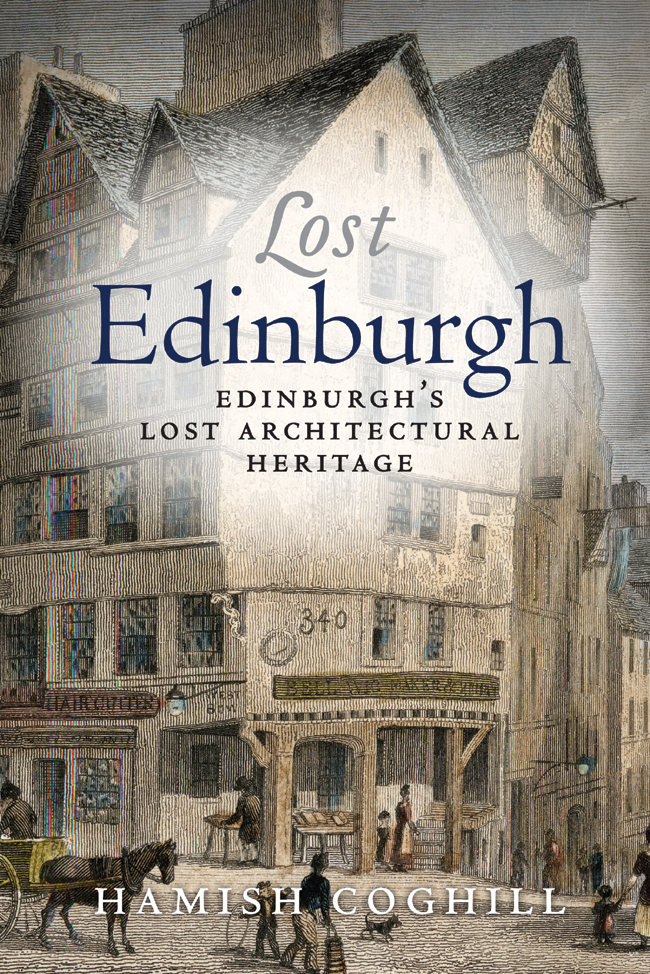

L OST

E DINBURGH

This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

This edition first published in 2008

Copyright Hamish Coghill 2005, 2008, 2012, 2014

The moral right of Hamish Coghill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 84158 747 9

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 624 3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Murray, Gregor, Isobel, Abegail and Alasdair,

and their Grandma, Mary

CONTENTS

Chapter One

PARADISE LOST

Chapter Two

SCORCHED EARTH

Chapter Three

HOLY CITY

Chapter Four

THE LORD IS ANGRY

Chapter Five

COMETH THE MAN

Chapter Six

LONG BLACK SNAIL

Chapter Seven

CONFLAGRATION

Chapter Eight

BOWED OUT

Chapter Nine

DESTRUCTION

Chapter Ten

DESECRATION

Chapter Eleven

EXODUS

Chapter Twelve

MARKET DAYS

Chapter Thirteen

NOTHING REMAINS

Chapter Fourteen

BATTLE JOINED

Chapter Fifteen

CHURCH LIFE

Chapter Sixteen

DOWNS AND UPS

Chapter Seventeen

JAILHOUSE BLUES

Chapter Eighteen

OUT OF FASHION

Chapter Nineteen

CURTAIN DOWN

Chapter Twenty

MILE OF CHANGE

Chapter Twenty-one

END OF THE LINE

Chapter Twenty-two

HURTFUL TEMPTATIONS

INTRODUCTION

Reverence for mere antiquity, and even for modern beauty,

on their own account, is scarcely a Scottish passion.

Lord Cockburn, Memorials of His Time, 1856

One cannot, however, expect to preserve everything if improvements

are to be made to meet present and future needs.

A Civic Survey and Plan for Edinburgh, 1949

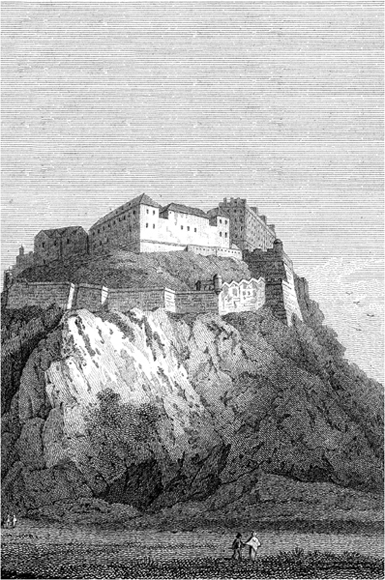

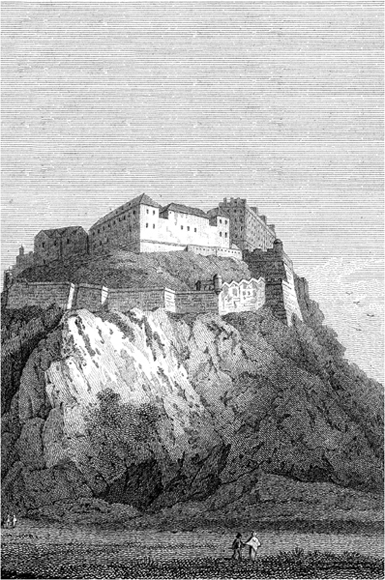

The tourists who flock into Edinburgh in their hundreds of thousands every year gladly walk the Royal Mile between the Castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse. They look at old buildings, peer into closes those dark, narrow thoroughfares dividing the high structures to see in some of them simply stumps of houses. They sense in the High Street and in the Canongate reconstruction a feeling of antiquity.

But how would they and Edinburghers feel if they could still explore the Old Tolbooth outside St Giles Cathedral, or walk down the Parliament Stairs, loiter outside the French Ambassadors Chapel in the Cowgate or even take a bracing stroll along Portobellos Victorian pier?

In growing from a huddle of huts round a fortess on a volcanic rock into an international and cosmopolitan city, Edinburgh has had to change. And inevitably there will be more changes, if for nothing more than to meet the demand for more houses, more office space, bigger and better shopping centres, new roads and sports facilities. That is part of inhabitants relentness demand on their city.

With the Old Town and New Town areas now a World Heritage Site, the worst destructive excesses of the past should not be allowed to occur again.

But what destruction Edinburgh has seen over the years, sometimes by enemy hand, often self-inflicted. Campaigns to conserve have been fought, occasionally won, more often lost, and another slice of the townscape has gone.

It is impossible to record every building which has been replaced over the centuries because in a changing city things can happen very quickly, not least when, as occurred on several occasions, it was put to the fire by English armies. Later, the Victorian improvers and successive developers shared one thing a burning desire to carry out their plans come what may. Anything that was in the way of a new street or bridge or civic development was knocked down.

When we talk of the New Town, we have to remember that the first houses were started there in 1767 an initiative driven by men of vision who saw that the city had to be shaken out of its moribund stupor as buildings were literally tumbling down around the citizens heads. But was it necessary a century later to be ripping away much of the medieval town?

Many of the once outlying village communities were also swallowed up by the expanding Edinburgh or simply flattened. Where are the villages of Picardie or Broughton or St Ninians Row now, for instance?

The 20th century saw a growing appreciation that buildings with a place in the citys history, for archaeological reasons or otherwise, deserved to be protected where possible, but George Square, for example, is a small shadow of itself and its 18th-century charm is lost to the present and future generations.

Changing demands have seen once-great industries, such as brewing and printing, shrink to an incredible degree in what was both a great brewing and printing centre, renowned throughout the world. Who now recalls Thomas Nelsons Parkside works, across the road from where the Royal Commonwealth Pool stands, and all the other famous printing houses? Who has swallowed all the ale-makers?

So many industrial or factory sites are now filled with flats. Even Powderhall Stadium, a multi-purpose sports ground, has fallen to the changing times and houses stand on the former greyhound track.

No longer do the mills on the Water of Leith clank in their sheltered vale. Again, the old buildings make good houses or, even better for the house-builders, the cleared sites provide room for many homes. We have seen in recent years supermarkets built on sports fields, more houses on every spare corner, a resurgence in Leith Docks of super-development and the start of the process to transform the citys northern boundary in the Waterfront scheme. A successful fight was waged to save the local polo field at Colinton, Meadowbank Stadium looks like it has come to the end of its useful days, the characters like the one-man band or the hurdy-gurdy woman who once wandered the streets are no longer with us. Our old trams are mere memories, and the new tramway system, one of the most contentious issues in Edinburgh in recent years truncated, over budget and years behind schedule will never replace in our hearts the shoogly monsters of yesteryear.

In 2002, the frequent curse of Edinburgh the raging inferno ripped through a chunk of the Cowgate, necessitating the removal of the gutted remains in that street and up above on South Bridge. Another slice lost, but a challenge to planners and architects to combine a historical site with a worthy 21st-century renaissance.

This book aims to leave the reader with at least a flavour of what has been lost on the building front and concentrates on that aspect. Along the way, however, I hope it also gives something of the life of this old town.