TRADITIONAL BUILDING MATERIALS

Matthew Slocombe

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Thatch anchored by ropes tied to timbers projecting from the gable end of a house on the Isle of Man.

CONTENTS

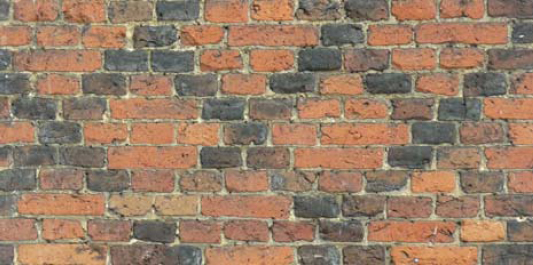

Diapering on a Suffolk house. Dark headers (bricks used with their ends outward facing) which have been over-burnt in the hottest part of the kiln form a decorative pattern in combination with lighter-coloured bricks.

A Leicestershire cottage roofed with corrugated iron. Thanks to its lower maintenance requirements, metal sheeting often replaced thatch from the late nineteenth century beginning a new rural roofing tradition. The cottage has squared, coursed rubble walls, exposed timber lintels over windows and a chimney rebuilt in brick.

INTRODUCTION

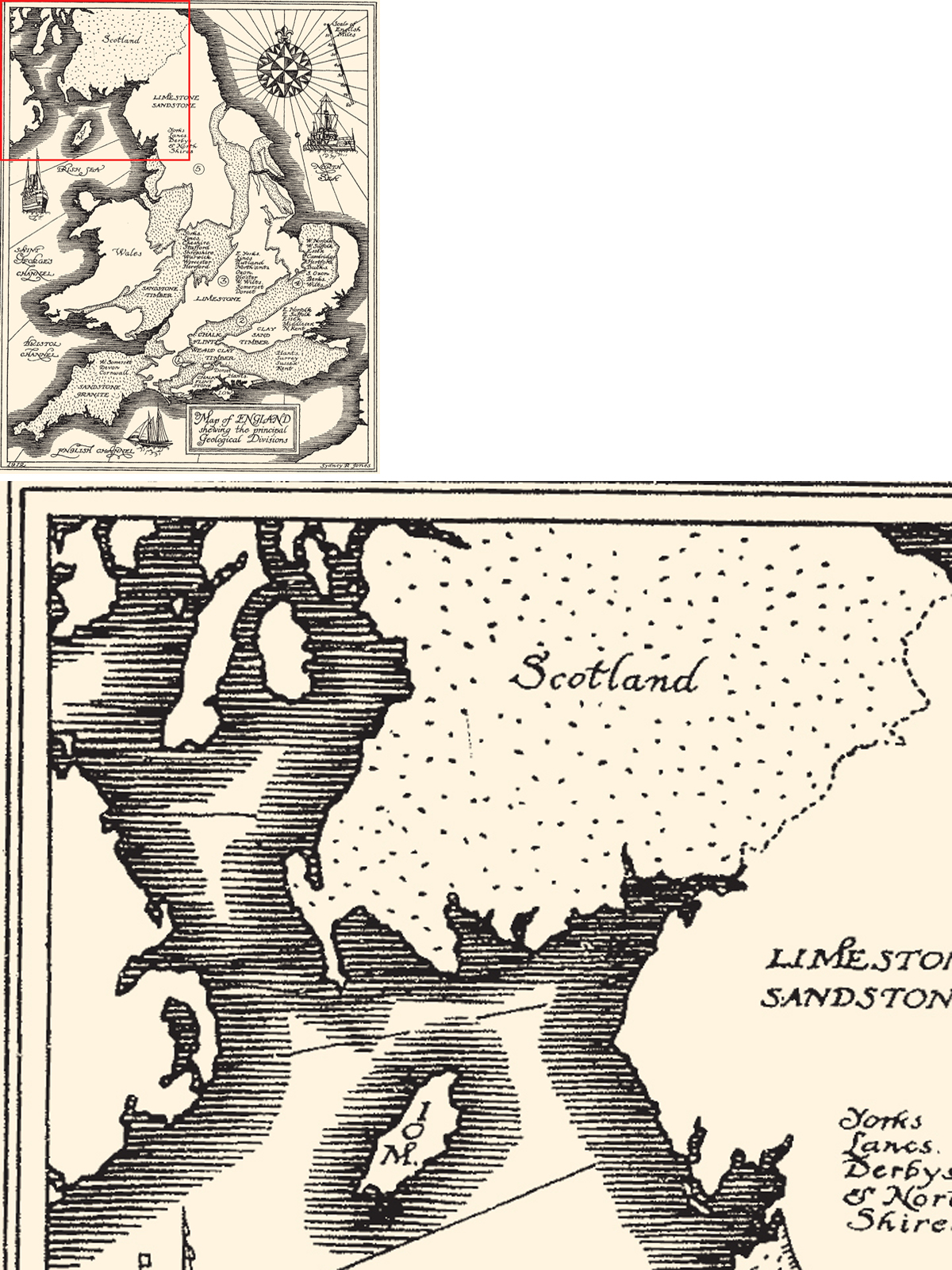

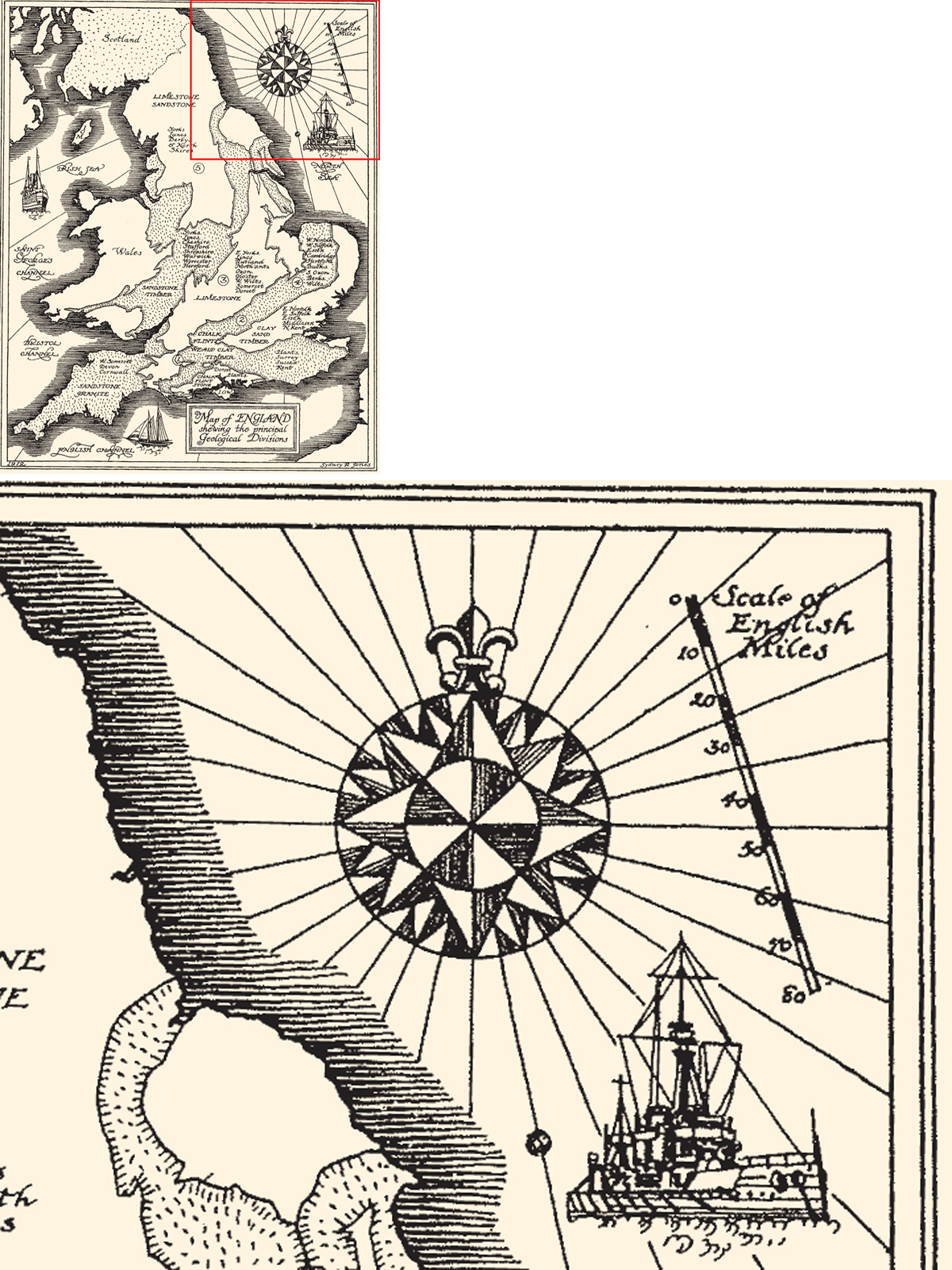

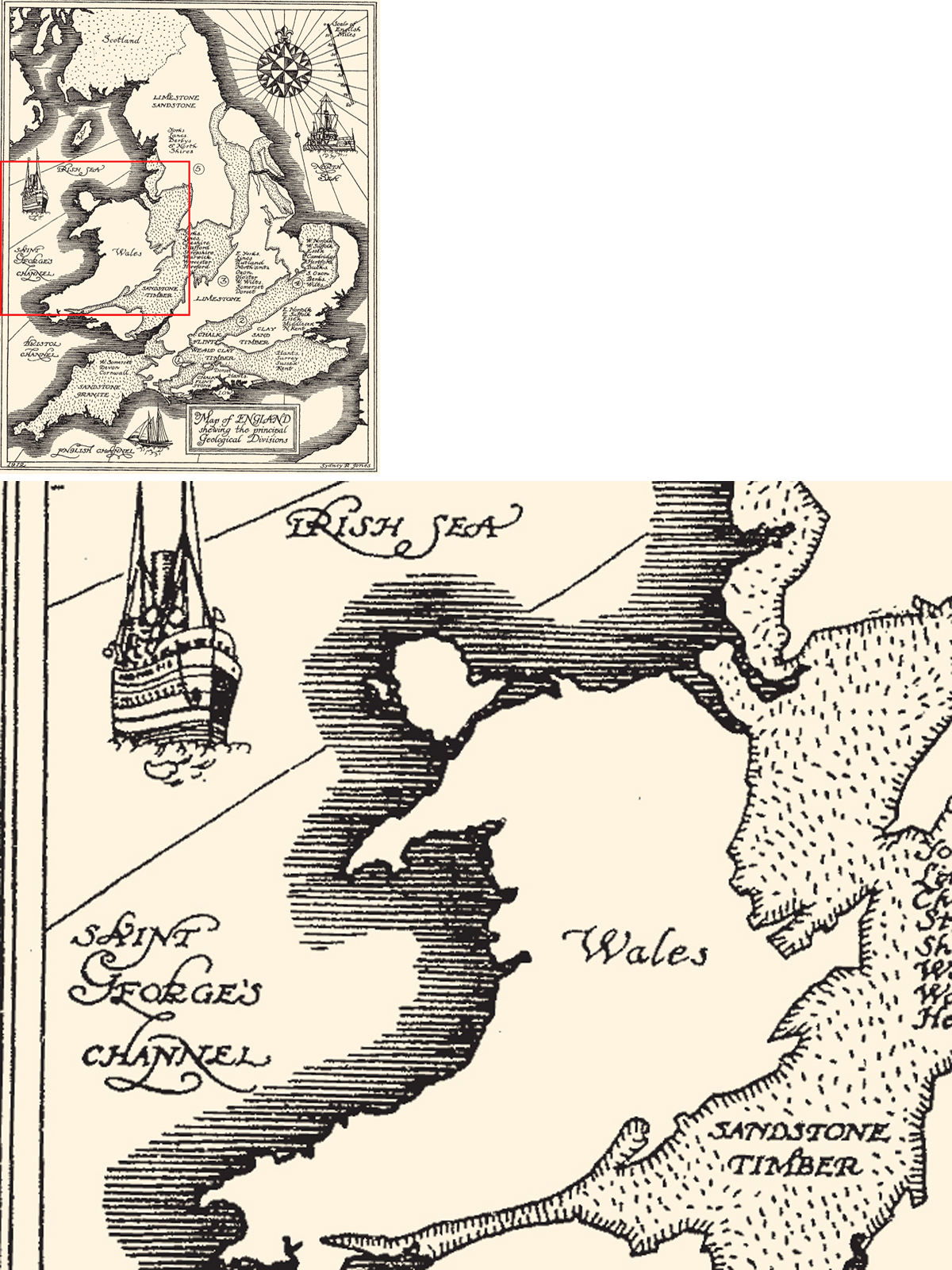

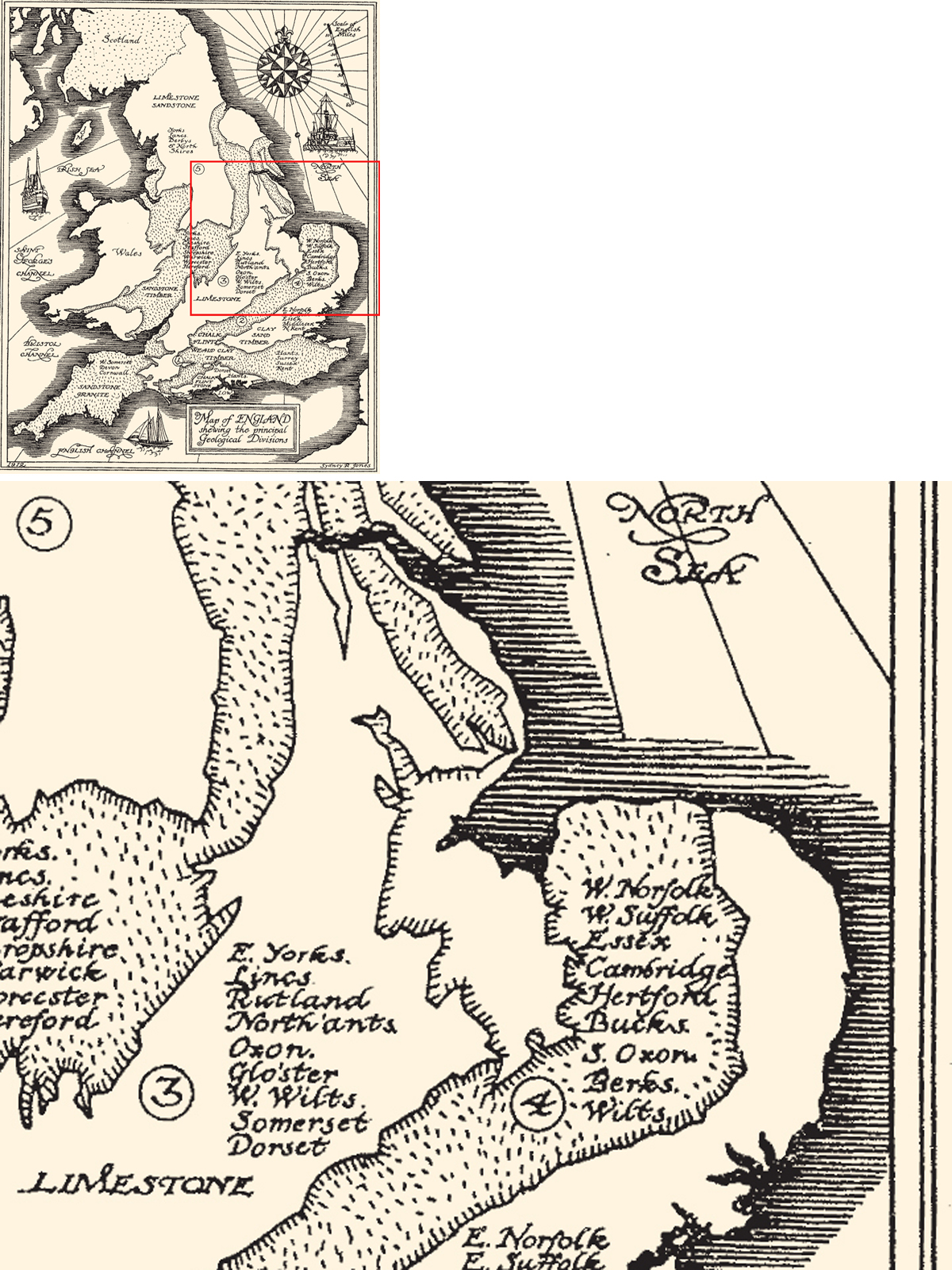

T HE EARLIEST HOUSE so far discovered in Britain is around 10,500 years old; archaeologists found it at a site near Scarborough. It represents the first point at which a settled domestic existence can be identified for people living in the British Isles. Like much traditional British housing, the walls of the Scarborough building had a structure made from a material close at hand: timber. This has been, and continues to be, a staple of domestic construction, even though the ways in which wood was used have changed and developed. Building with timber occurred in nearly all areas, though traditions were naturally much stronger where woodland was plentiful. Sparsely wooded areas, like the Scottish islands, inevitably used timber more selectively. Where timber was not the primary structural material, a different method of constructing walls was required. Building with earth or stone was the usual alternative, though brick grew in popularity as production methods developed. Common approaches to construction exist across Britain, but the materials available locally and the craft traditions involved in their use have shaped the character of regions and localities.

This book offers an introduction to the wide variety of materials and techniques used for the construction of Britains traditional buildings. It focuses on housing, and specifically on its most fundamental elements: walls and roof coverings. All building materials, however innovative at first, become traditional if they are used in similar ways over a considerable period. For the purposes of this book the term is applied to walling and roofing materials in well-established use before the twentieth century. The period around 1900 was a transitional point in construction before new materials and methods, such as concrete blockwork, cavity walling and damp proof courses became widespread. Although materials such as brick and stone have continued to play a role in modern cavity walled buildings, this book looks at earlier traditions where earth and masonry formed solid walls, and substantial timbers were used to create a structural framework. For much of the past, thatch was the material normally used to cover house roofs, with stone slates or lead sheets reserved for the buildings of the wealthy or where manufacture was local. Fired clay tiles and materials like Welsh slate took off when production and transportation allowed.

Pembridge, Herefordshire, c. 1900, with a rich mix of brick, timber framing, thatch, stone roofing tiles, plaster and limewash.

A large team of builders from the early twentieth century, wearing flat caps not hard hats. Note also the use of timber scaffolding.

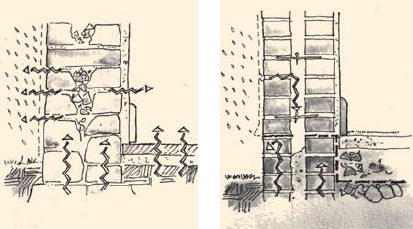

Traditional masonry walling involved solid wall construction, without damp proof courses or deep foundations (left). From the mid-late nineteenth century, modern cavity wall construction began to be introduced (right). The arrows indicate the movement of rainwater and ground moisture.

The ways in which traditional building materials have been used across Britain are often as recognisable as a regional accent. The steeply pitched thatched roofs of East Anglia are distinct from the shallow sloped, stone slate coverings of the Pennines. The softly rounded earth walls of Devon contrast with the crisply cut sandstone of Edinburgh. But whether Upland or Lowland, rural or urban, inland or coastal, all areas have made practical use of the materials to hand, with little waste. Thatching materials were the by-product of the harvest, and in rural areas field stones, which were a nuisance to agriculture, could be removed and recycled for house walls or for the plinth at the base of earth or timber buildings. In all areas the basic purpose of housing was to offer shelter from the variable and sometimes hostile climate. As one rental book of 1698 from Warwickshire noted, the Great Lord of Heaven and Earth hath reserved such a power in his hand that he can and doth att his pleasure send a cold winterly season in the midest of the Spring. Provision for heavy rain was made in most parts of Britain, with the roof overhanging the walls at the eaves and materials like earth and timber kept off damp ground. Richard Carew noted in 1602, in his Survey of Cornwall, that as for Brick and Lath walls, they can hardly brooke the Cornish weather, and the use thereof being put in trial by some, was found so unprofitable, as it is not continued by any. Traditional construction might almost be viewed as a form of natural selection. Builders around the country evolved techniques that allowed the materials available to be used in ways that could withstand local environmental conditions. On the west coasts of Wales and Scotland straw ropes weighted with stones helped keep the thatch in place against fierce winds; and lime or clay renders were frequently applied to protect exteriors.

A sixteenth-century carved oak bench end from north Devon depicting builders ladder and axe.