Chapter 1

Inexhaustible Terrain

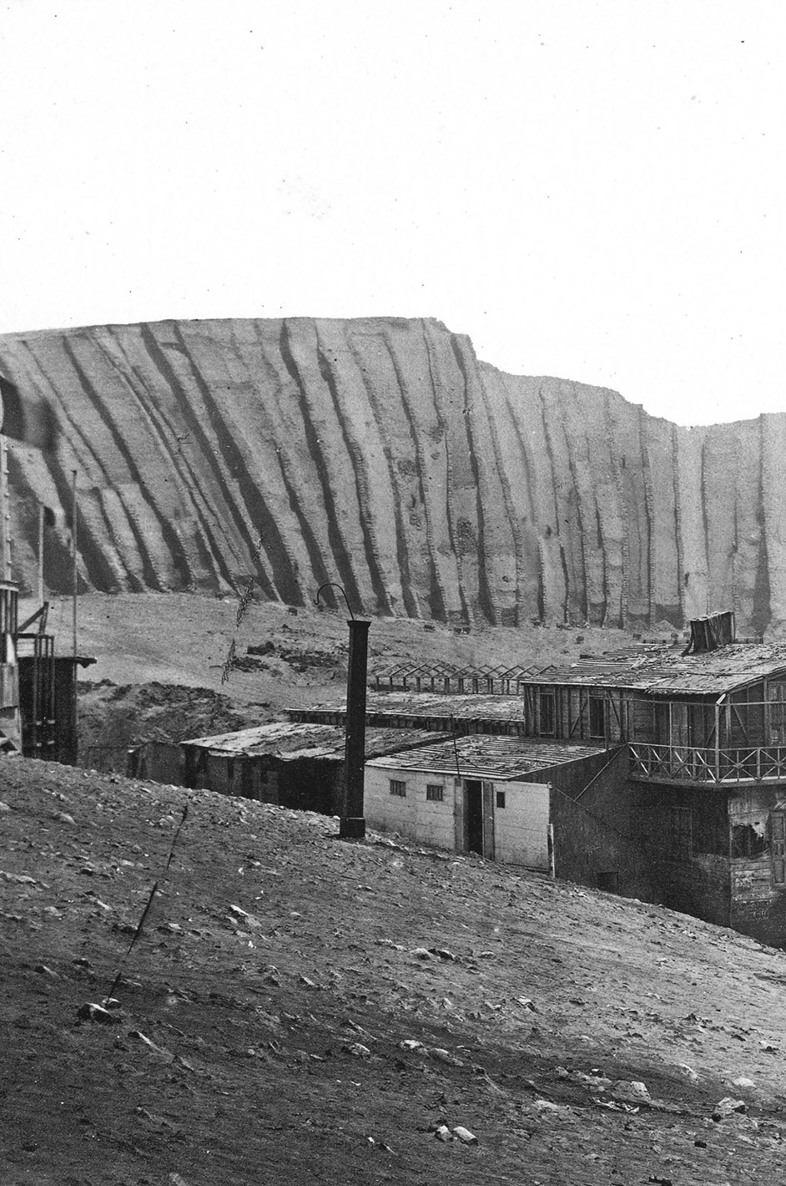

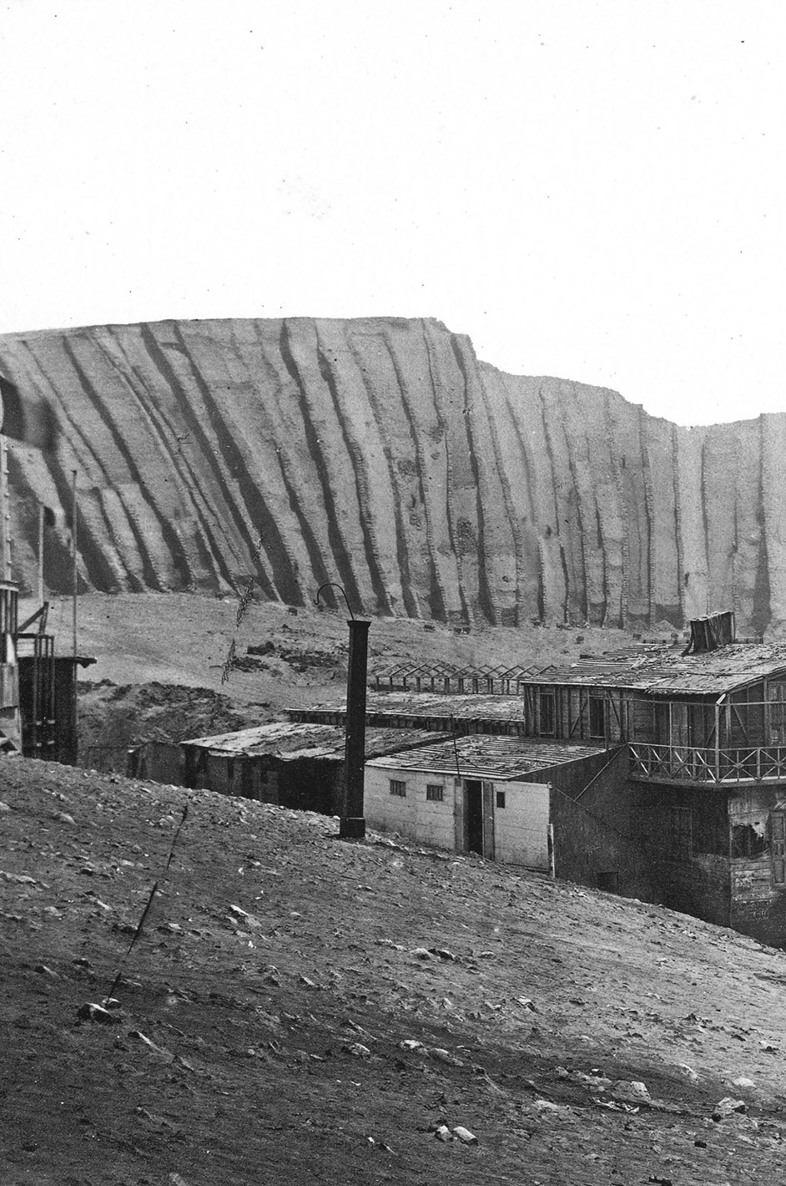

Detail of guano deposit and settlement, Chincha Islands, Peru, 1862

Source: Courtesy of New Bedford Whaling Museum.

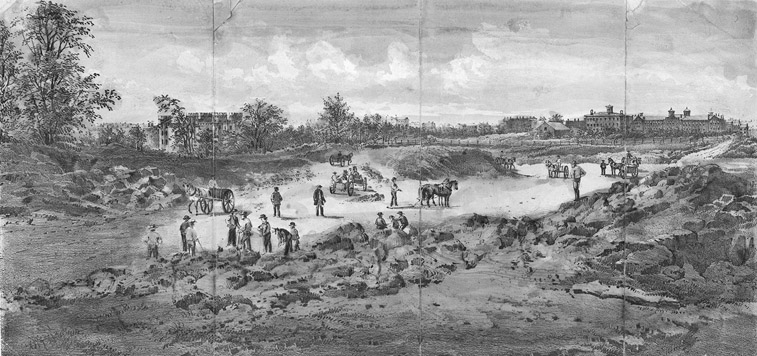

Detail of Sheep Meadow looking southwest, Central Park, circa 1905

Source: Photograph by William Hale Kirk ( William Hale Kirk/Museum of the City of New York).

To a blade of grass, access to nutrients means everything: nitrogen accelerates growth and makes for bright green color, phosphorus builds stronger roots and winter toughness, and potassium stiffens blades to make a sturdier surface. To Frederick Law Olmsted, carefully fertilizing and improving the soils of Central Park was essential to create the sweeping pastoral landscape that it would become famous for. The success of the turf would impact the beauty and success of the park as a whole. The park looked like a farm, but it also operated like one. Olmsted experimented with new fertilizers being used in farms at the periphery of the expanding metropolis, including horse manure from street sweepings, night soil from Manhattans privies, manufactured poudrette , and guano. Of the fertilizers applied to Central Park at the time, guano (desiccated seabird excrement) was the most potent, exotic, and novel. Unlike composted manures and fertilizers incorporating local industrial byproducts, guano was imported from Peru and the South Pacific.

With thousands of miles between them, the Chincha Islands of coastal Peru and Central Park are improbably connected. This chapter follows a trace amount of Peruvian guano applied to the initial soils of Central Park in the early 1860s. While small in volume, this particular fertilizer application reflects guanos transformative role in farms surrounding New York City and other industrializing metropolises in North America and Europe. As farmers shifted from self-sustaining to industrial models, and substituted more processed and mined fertilizers for the composted animal manures traditionally used, nutrient cycles expanded from the scale of the farm to the urban region to the planet. In the quest to recharge depleted soils in one place, ecological deposits and humans were exploited and exhausted in another. The case of guano in Central Park more broadly reflects the growing metabolic rift of the nineteenth century, as expanding nutrient cycles and enslaved human labor were invisibly, yet directly, linked to the public landscape.

Natures Reciprocity System

Before long, Olmsted and Vaux argued, Manhattan would be crowded with buildings and noisy, noxious streets.

Pastoral scenery could do this best. Olmsted pictured a meadow where shadows on the far ground would produce illusions of variation and distance, and where trees and topography would hide the buildings along the parks boundaries. Pastoral scenery referred directly to working agricultural landscapes and the type that many of New York Citys new residents had migrated from. No longer in fields, citizens now worked in factories estranged from the land and its cycles. Visitors experienced the remediating effects of the different environments, but they would also see the park working as a farm. At Central Parks Dairy, children could get affordable, fresh milk of higher quality than that more commonly available from brewery cows. The public could watch hay and rye crops growing and watch as workers periodically scythed it down to feed the parks animals. The Sheep Meadow the gem of the designs pastoral landscape was the parks most literal agricultural simulacra.

Sheep Meadow looking southwest, Central Park, circa 1905

Source : Photograph by William Hale Kirk ( William Hale Kirk/Museum of the City of New York).

Robert L. Bracklow, Sheep in Sheep Meadow Central Park, circa 18901910, glass negative, 5 in. 7 in.

Source : Robert L. Bracklow Photograph Collection, 18821918 (bulk 18961905), nyhs_pr-008_66000_1000, Photography New York Historical Society.

The Sheep Meadow, originally named the Parade Grounds to satisfy competition requirements for military programming (and intermediately called The Green), looked like a real pasture. If the grasses made a pastoral scene, a flock of Southdown sheep activated the agricultural stage from 1864. Their droppings helped the grass grow quickly. While the sheep produced a symbolic image of a farm, their role in the ecological functioning of the soil and grass was part of this image.

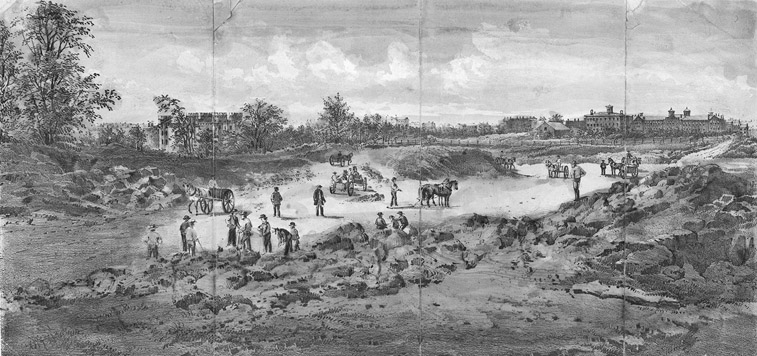

As the new contours of Central Park were formed, workers mixed composted horse manure and night soil into the top layers of the soil, distributing it at 300 or 225 cartloads per acre, respectively. Horse and human manures were abundant and cheap, and so they were the primary soil amendments. Manures give plants access to nutrients slowly by changing the quality of the soil; they aggregate soil particles, which makes them spongier and absorptive and provides conditions for microorganisms to thrive. With the help of specialist fungi, bacteria, and other organisms, manures are transformed into the nutrients that plants require.

Guano, in contrast, gives plants more highly concentrated nutrients, immediately, without transforming soil quality or its microbiota. Much more potent than farm animal or human manures, guano was applied at five bushels to the acre, or approximately half a cartload per acre.

Construction activity in Central Park, 1858

Source : Lithograph by George Hayward (Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations).

While the Central Park Annual Reports provide few details on practices as specific as fertilizer application, the Seventh Report goes into detail about a range of fertilizer types used to prepare the soil in different areas of the park. The report describes how guano was applied in the 11.5 acres east of the Old Reservoir (the present-day Great Lawn) and the 2 acres west of it, at 500 pounds per acre. Guano in this case was a mix of one part Peruvian to three parts Baker Island guano (American guano from the South Pacific), mixed with eight pounds of salt per 100 pounds of guano. Biologically speaking, getting this perfection involves aborting the plants sexual reproduction, preventing the setting of seed and instead stimulating the plant to reproduce rhizomatically, rendering a thicker, denser mat.

Shortly after opening to visitors, a regulation prohibited the public grazing of animals (apart from the parks own flock) on the parks grounds. Not only would public use of the turf effectively destroy it, public activities threatened the quiet, reflective qualities that Olmsted and Vaux desired for the meadows. Central Parks green meadow scenery, supposedly constructed for the masses, was off limits. This contradiction between grass and its users foreshadows the 100-year development of a now multi-billion-dollar turf industry, which I will return to later on.