Looking into the past: the double door frame on the first floor of Owlpen Manor, and a glimpse into Queen Margarets Room.

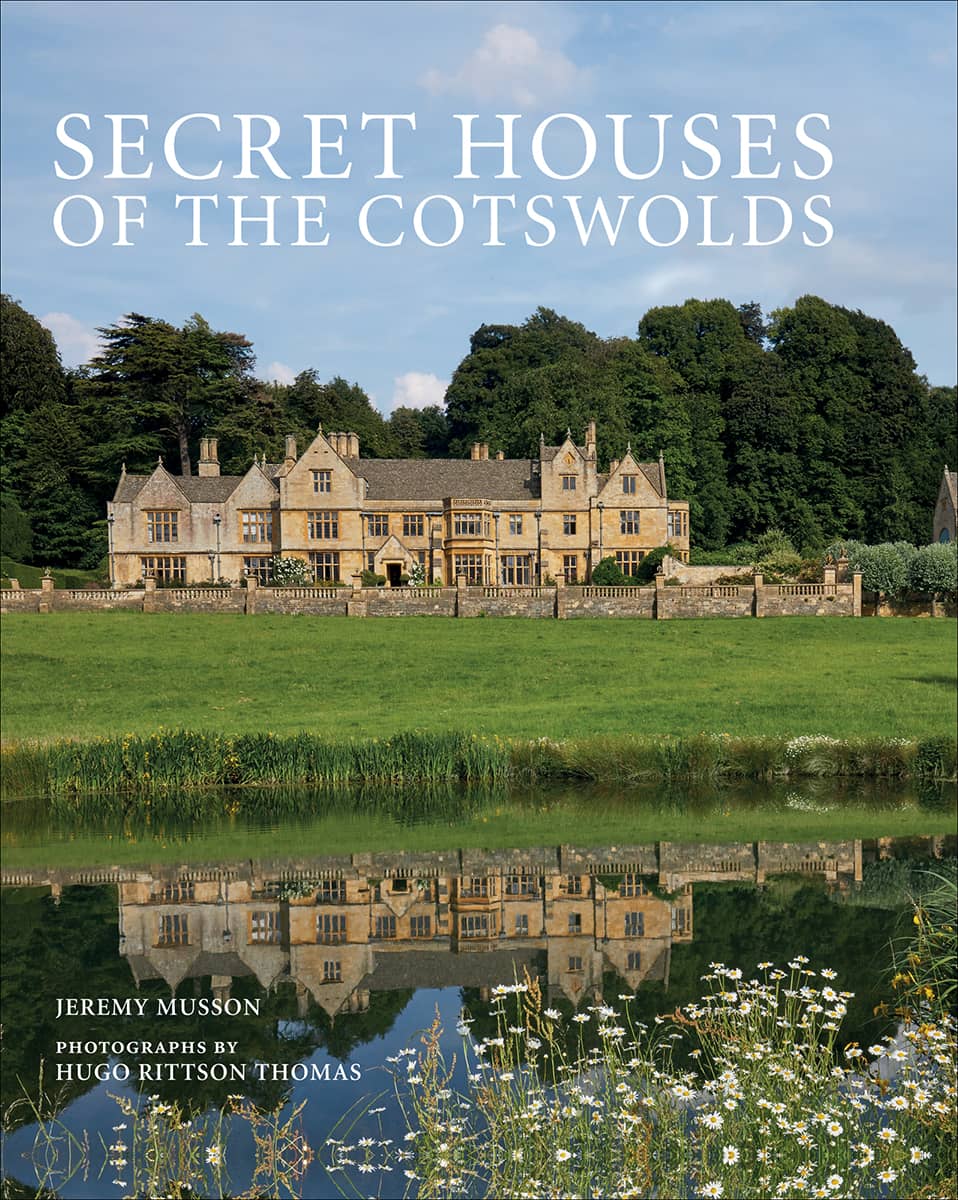

T HE C OTSWOLDS is a beguiling region, famous for enchanting landscapes, picturesque villages and old houses for some it is the very essence of England. We deliberately take a very broad definition of the Cotswolds for this book, including Gloucestershire and a good part of Oxfordshire, informed principally by the dominance of oolitic limestone. A wealthy area in the medieval, Tudor and Stuart periods, the Cotswolds became something of a backwater in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and thus preserved a strong rural character. It was in a sense discovered by artists and writers at the end of nineteenth century, especially characters such as William Morris, who admired the quiet poetry of the old stone buildings.

Morris famously leased Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, which he called the loveliest haunt of ancient peace, a phrase which evokes many of the remote stone houses set in their verdant narrow valleys. The old houses of the region have a feeling of solidity and survival. In 1987, James Lees-Milne referenced the range of colour encountered in the Cotswolds stone: shades of grey, mauve, cream, buff, honey, yellow and even orange, which he describes as often silvered over with lichen.

The elevated position of Hilles House, on the edge of the Cotswold plateau, reflects the high ideals of its creation.

My own interest dates back to the mid-1990s, when I joined the staff of Country Life magazine, and began an annual pilgrimage to the region to pick out beautiful and remote houses for publication. Christopher Hussey, my famous predecessor as architectural editor, had a special admiration for the Cotswolds, writing in 1934 that the architecture of the oolite ridge that runs from Lyme Regis to Stamford is a kind of domestic Touraine, the backbone of traditional English building.

So trips to the Cotswolds became the architectural historians equivalent of an office romance, as I became more and more interested in the country houses of the region, and made friends across the counties.

We stayed as a family in the old Grist Mill at Owlpen on one of our early visits, and were enchanted by the hidden quality of the house and garden there, and the picturesque vegetable garden. I recall being given a tour by Nicky (now Sir Nicholas) Mander, whose love of that house and that place has manifested itself in so many different ways. His friendship in the 1970s with the then very elderly Norman Jewson, the arts and crafts architect, gave him a direct and personal link to the world of William Morris, Philip Webb and their followers.

Lord Wemyss at Stanway has always been unfailingly generous with access to his remarkable house, and has welcomed many young Plunkett scholars of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (founded by William Morris in 1877), for whom I have been a tutor for a decade. They bring their sketchbooks and look, think and draw.

I was delighted to be introduced to Hugo Rittson Thomas, an accomplished photographer who himself lives in a Cotswolds manor house in Oxfordshire, with elegant gardens. He had already had a huge success with Secret Gardens of the Cotswolds, written by Victoria Summerley, and his background in portraiture gives him his own approach to viewing, framing and recording the country house with great subtlety and art.

It has naturally been a great pleasure and privilege to criss-cross the region visiting houses and interviewing owners for this book, to be on every visit reminded of the lush, steep fields, hidden valleys and dense woodland, and to realise how secret the Cotswolds is by the very nature of its topography. Even when passing through small, popular towns, within minutes you can be lost again in a landscape that seems to have hardly changed for centuries.

The selection is personal, a merging of Cotswolds country houses known to myself, and others known to Hugo. Ranging from the medieval to the very recent, most of the houses featured are private and not open to the public, and through this book are now shared with a wider audience. In each case my account encompasses the architectural history of the house, something of its character, and some conversation with the owners about how they came to the house, and why it looks as it does today. We learn about new generations moving in, about busy architects and gardeners, decorators, as well as collectors and artists, who all contribute to the ongoing story of the Cotswold country house.

I am indebted to the writings of Nicholas Kingsley, David Verey, Alan Brooks, Jennifer Sherwood, Sir Nicholas Mander, Christopher Hussey, Marcus Binney, John Goodall, Michael Hall and Mary Miers, as well James Lees-Milne and Hugh Massingberd.

In these pages we have a variety of older manor houses, Elizabethan and Jacobean mansions, a moated castle and another castle partly in ruins, two mid-Georgian classical houses of remarkable beauty, older houses remodelled in the Regency, and Victorian houses remodelled in the 1930s. There is a house associated with the famous Mitford sisters (Nancys fictional country house portraits were clearly inspired by her Cotswolds childhood), and another that inspired the lyrical account of growing up in an ancient house, The Music Room (2009).

I am especially pleased that many of those I have interviewed are owners who have bought old houses in recent years and poured love and money into them, to preserve their beauty and make them family homes; to live in them and add their stories to the long history of human occupation that goes before them.

It is also a pleasure to include one of the newest country houses of the Cotswolds, with its light-filled interiors and views framed like landscape paintings. To all the owners we are immensely grateful for their generosity of spirit. Private owners care for and preserve so many of our historic houses, and deserve our respect and thanks.

1

Asthall Manor

Oxfordshire

S OMETIMES IN THE C OTSWOLDS you can take a turn off a busy road and find yourself heading into a valley of lush fields and woodlands. In these parts, the villages have a quiet and timeless feel, while the church and manor house provide the visual focus, as they have done for generations. There has been a manor house at Asthall, near Burford, for many centuries, and the house we see today, with a hall range at its core between two gabled cross wings, dates principally to the early and mid-seventeenth century. This was given a more regular frontage in the later nineteenth century, and extended by 2nd Baron Redesdale from 1919.