Contents

Guide

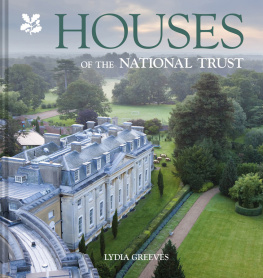

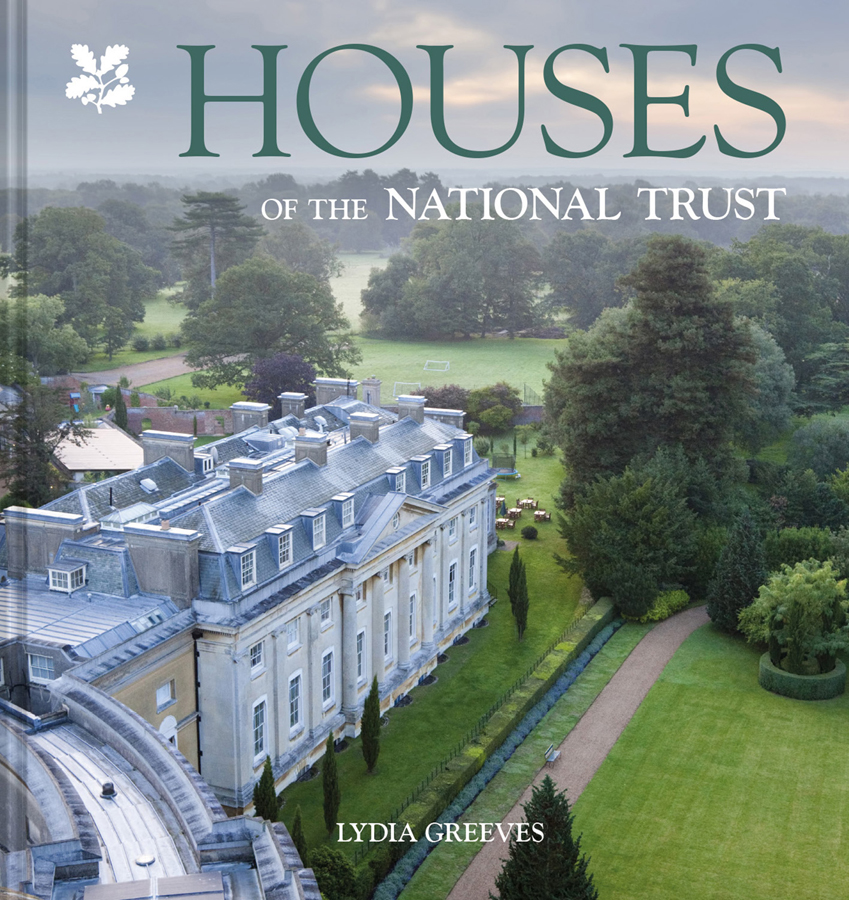

HOUSES

of theNational Trust

HOUSES

of theNational Trust

Lydia Greeves

Contents

Introduction

The National Trust cares for a large and wonderfully diverse collection of buildings. Of those covered in this book, most are houses, but there is also a good representation of other types of building, from ruined castles and former monasteries, inns, chapels and follies, to the watermills, windmills, tithe barns and market halls that once played such an important part in the rural economy. Between them, they span almost a thousand years of history, from the time of William the Conqueror to the present day. Among the earliest is the remarkable one-storey Norman hall at Horton Court, deep in the Cotswolds, which was built for the prebendaries who were responsible for the church across the road. Dating from the same period is Corfe Castle, now a dramatic ruin standing high on the Purbeck Hills, but once an impregnable stronghold, one of the many built by William the Conqueror in the years after his victory at Hastings to consolidate his hold on his new kingdom. The most recent buildings include the terraced house on a post-war Liverpool estate where Paul McCartney and John Lennon, then in their teens, worked out their first songs and developed the individual sound that would come to define the Beatles, and two examples of modernist domestic architecture: 2 Willow Road, looking over Londons Hampstead Heath, and The Homewood, in leafy Surrey.

Although the preservation of buildings and their contents is now seen as a core aspect of the Trusts work, this has not always been so. For the first 40 or so years of its existence, from its establishment in 1895 until the 1930s, the Trust was primarily concerned with the acquisition and protection of the countryside, a focus which partly reflects the principal aims of its founders, Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley. This determined trio had backgrounds in the Commons Society and the Lake District Defence Society and were only too aware that the beauty of England was being eroded by uncontrolled development. For them, the National Trust was primarily a vehicle for educating public opinion and for acquiring and safeguarding threatened landscapes that were worthy of protection. Among the first properties to come to the Trust were a stretch of coastline in Wales, part of Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire, Brandelhow on the west side of Derwentwater in the Lake District, and the shingle spit of Blakeney Point in Norfolk.

Twisted finials and chimneys ornament the south front of Elizabethan Barrington Court.

The Trusts remit to preserve places of historic interest as well as natural beauty was at first interpreted as applying to small, ancient buildings, as typified by the two properties the Trust acquired in its initial ten years of existence. The first, bought in 1896 for 10, was Alfriston Clergy House, an exquisite, half-timbered building dating from c.1400 that was in an advanced state of dilapidation. A few years later, in 1903, the Trust bought the tiny medieval manor known as the Old Post Office in the centre of Tintagel, which was threatened by redevelopment for the tourist trade. To be strictly accurate, the Old Post Office was the third building to be acquired by the Trust as, in 1900, Robert Hunter had negotiated the gift of the semi-ruinous Kanturk Castle, a fortified Jacobean manor in Co. Cork. When Ireland was divided in 1921, Kanturk lay in what is now known as the Irish Republic and in 1951 the Trust gave it to An Taisce, the National Trust for Ireland, on a thousand-year lease.

Significantly, these buildings came to the Trust without any contents and this was also true of Barrington Court, the Trusts first substantial property, which was bought in 1907. The purchase price and bill for initial repairs together came to the then massive sum of 11,500. Built of golden Ham Hill stone and with a roofline display of twisted finials, Barrington is a great Elizabethan mansion with an exterior that is as dramatic as that of Montacute, which lies only a few miles away. When bought, though, the house was a shell in an advanced state of dilapidation and without many of its fittings, which had been taken out and sold. Maintaining this property, which was a constant drain on the Trusts slender resources, proved to be a salutary lesson in the pressures and difficulties involved in caring for houses of this size and the need for endowments to cover ongoing expenditure. But anyone who has wandered through Barringtons atmospheric rooms or sat in the beautiful compartmental gardens with their Jekyll-inspired planting will know the Trusts decision was the right one.

Fortunately, in the years before the Second World War, just at the time when owners of great country houses were being faced with ruinous increases in taxation, death duties and running costs, a change in the Trusts status in 1937, which enabled the Trust to hold land and investments to provide for property upkeep, and the introduction of the Country Houses scheme in 1940, by which owners could transfer their houses to the Trust, together with a suitable tax-free endowment, while continuing to live there, paved the way for a number of the finest properties, together with their contents, to be gifted. Blickling was given to the Trust in 1940, Wallington was acquired in 1941, Cliveden in 1942, West Wycombe in 1943, Polesden Lacey and Lacock Abbey in 1944.