Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Alexander Benjamin Craghead

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62584.794.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016934219

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.309.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PREFACE

This book both is and is not about architecture.

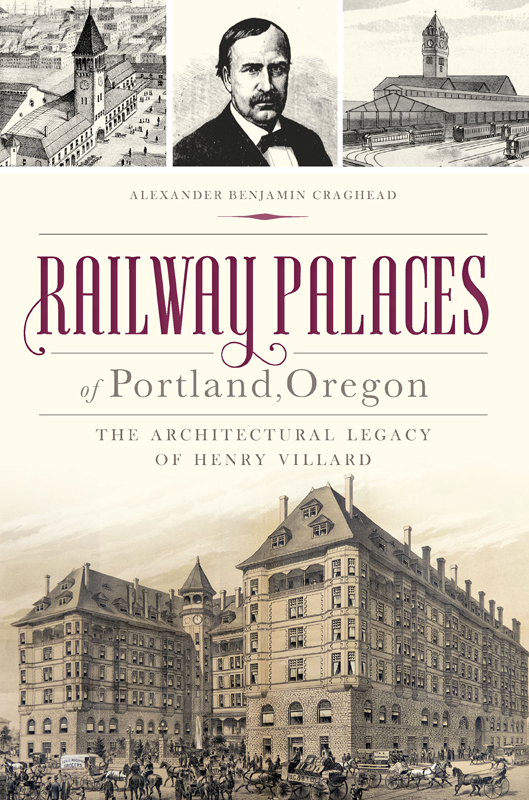

At one level, it tells the story of several buildings either proposed for or constructed in Portland, Oregon, during the Gilded Age. Three structures in particular are important. The first is the citys Grand Central Passenger Station (1882), the second is the Portland Hotel (188390) and the last is Portland Union Station (1896). The first two were designed by McKim, Mead & White, arguably the most important U.S. architecture firm of the late nineteenth century, and the third was designed by Henry Van Brunt and Frank Howe. All three are important transitional designs. For McKims firm, the station and hotel projects are a crucial iteration in the development of their design aesthetic. Union Station, meanwhile, embodies both the end of the Romanesque design language and the new dominance of a Renaissance Revival sensibility.

At another level, however, this is a story that goes far beyond the esoteric succession of anachronistic architectural styles. In many ways, it does not matter whether they were made of stone or brick or even if they were built or remained unrealized. These buildings are a way to understand city making in a time and place where urbanity was both new and rapidly developing. They expose how a new community grasped toward metropolitanism through the construction of public and semipublic architecture. Their story shows how the business elites of Portland, despite the relative youth of their community, defined legitimacy through the artifice of insiders and outsiders. Above this, these structures reveal how the frontier city, despite local boosterism, is only partly a product of local action. Civic rivalries masked civic similarities so that while Portland hoped to be a rival to San Francisco and was rivaled by Seattle, all three cities were dependent on the same capital, politics and ideas emanating from distant centers of power. The West seen in this book is not the successively developing frontier of Frederick Jackson Turner. It is a region where urban development dominates the rural; a place where the landscape is shaped by corporate, not individual interests; and where settlement is directly part of a global network of investment and trade.

The scope of this subject requires a more wide-ranging approach, and much of the narrative hinges on the actions of one man, Henry Villard. Arriving in Portland in the mid-1870s as an impromptu auditor, Villards ascent to the highest echelon of U.S. financiers is exemplary of the forces that shaped the West in the Gilded Age. By all practical measures, he was an outsider. Born in Germany, he foregrounded his Europeanism (rather than Americanizing), acted as an envoy for foreign capital and never called the West his home. Conversely, the Portland business elite welcomed him as an insider, and in turn, he became a patron rarely equaled and never exceeded, often treating the advancement of Portland as inseparable from his own. In his European eyes, the city and region were not a space of yeoman culture leading toward an American, agrarian democracy. They were, instead, a second Rhineland in the making, a place of cities, industry and high culture. Villard, then, treated the West not as a Turnerian birthplace of a uniquely American culture but as an extension of European culture. His architectural commissions for Portland embody these ideas, displaying his deeply urban enthusiasm for a great civilization facing the Pacific. While Villards unique position of power and unique background might seem to make him an exception, the actions of the mostly American-born Portland business elite mirror his own, showing that Villard differed from his domestic colleagues more in scale than in intent.

The goal of this book is to use the story of Villards architectural commissions for Portland to unpack the U.S. West during the Gilded Age, and to do so, I have made particular stylistic choices. While full understanding of the past is impossible, I want to communicate the ambition and the sense of unlimited possibilities that confronted people of the nineteenth century, much as it confronts us in our lives every day. I have thus adopted a literary style, hoping to sneak in through the prose an immersive experience of another time powerful enough to wipe away the 20/20 hindsight of the present, to disorient the reader from what they already know. I have attempted to reconstruct the geographic names of the period, so that D.C. is Washington City, Portlands Front Avenue is Front Street and so forth. It is my hope to make the ghost of Oscar Lewis proud.

The chain of events that led to the creation of this book is long, intricate and difficult to lay out with clarity, but it is certain that this book would not exist without Dan Haneckow. Many of the conceits and ideas within this text were born from countless lunch conversations and speculations about Portlands Gilded Age past, and on a more practical level, it was Dan who introduced me to the publisher, setting off the chain of events that ultimately led to the commission of the book. It also grows out of two other projects: the first, a collaboration with photographer Joel E. Jensen that investigated the cultural history of the American railway depot and the second, a public lecture on the history of Portland Union Station for the Architectural Heritage Center. For these, I must thank Joel, as well as Jeff Smith at the National Railway Historical Society, Jeff Brouws and Wendy Burton, Jim Heuer and Robert Mercer, and Val Ballstrem at the AHC.

I must thank several individuals and institutions for their assistance with this work. At the forefront of these are Brian Johnson, Mary Hansen and the entire staff of the incomparable Portland Archives and Records Center. Additionally I want to thank Tim Askin; the Bancroft Library and the Environmental Design Library at the University of CaliforniaBerkeley; the Ben Holladay Society; Norm Gholston; Ken Hawkins; the John Wilson Special Collections at the Multnomah County Library; the Library of Congress; the Minnesota Historical Society; National Archives and Records Administration; the Oregon Historical Society; Sheldon Perry, the Portland Development Commission; the Ryerson-Burnham Library at the Art Institute of Chicago; and last, but not least, the University of Oregon Archives. For any omission from this list, I present my sincerest apologies.