Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by JD Chandler

All rights reserved

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978.1.62584.667.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chandler, J. D.

Hidden history of Portland, Oregon / JD Chandler.

pages cm. -- (Hidden history)

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-198-3 (pbk.)

1. Portland (Or.)--History--Anecdotes. 2. Portland (Or.)--Biography--Anecdotes. I. Title.

F884.P857C53 2013

979.549--dc23

2013040954

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The debt that each generation owes to the past it must pay to the future.

Abigail Scott Duniway

CONTENTS

WHY IS IT HIDDEN HISTORY?

Portland has a two-faced history. On the one hand is the official story of the Rose City: growth and development under the leadership of a selfless group of merchant city fathers and rivalry for economic domination with other West Coast cities. On the other hand is the experience of the people who lived here: economic displacement, government dominated by corruption, graft and racial discrimination and resistance against the dominant system. The history of Oregon in the nineteenth century revolves around two bankrupt ideas: male dominance and white supremacy. In many ways, the history of our state, especially in the twentieth century, has been a struggle against these ideas. The history of the twenty-first century continues this struggle.

This book is history hidden in plain sight: fully documented in our archives, yet never told or, at best, hinted at in our history books. In a sense, it is a peoples history of Portland: an attempt to tell the story of the people who have lived on this spot, where two great rivers meet, for thousands of years. It is history for everyone. My hope is that, regardless of your background or experience, you will find someone here who looked like you, and their lives and experience will have meaning in your life. This is how history can live.

W.E.B. Dubois, one of Americas best historians, said that we dont talk about black history in this country because we are ashamed of it. That is the history that interests me: the history we are ashamed of, the history we have been too polite to mention and have forgotten. Join me now as I open the crowded, dusty closet of Portlands history and examine the skeletons bone by bone. Shameful history is not only the most interesting, but it also gives us the best chance to see how real people have dealt with injustice and oppression. Most of all, it is fun. Thanks for reading.

As always, errors and opinions in this book are my sole responsibility, but I am indebted to many friends and family who have lent their support and assistance. Thanks to Margaret H. Akbari, Barney Blalock, Steve Chandler, Carie Eisler, Ken Goldstein, Jim Huff, Finn J.D. John, John Klatt, Aubrie Koenig, Jacqueline Lawson, Sam Leighton, Tim Rich, Leslie Sand, Nancy Stewart and Jake Warren. In addition, there have been several institutions and organizations that have provided valuable assistance: the Ben Holladay Society, Multnomah County Library, Old Oregon Photos, Oregon Nikkei Center, Portland City Archive, Portland Maritime Museum, Portland Police Museum, Oregon State Archives and the U.S. Library of Congress.

PART I

Oregon Versus Ilahee

BEFORE PORTLAND

Did not your missionaries teach us that Christ died to save his people? So die we to save our people.

Tiloukaikt of the Cayuse Five

Most histories of Portland ignore the fact that people have lived at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers for as many as ten thousand years. They are able to do this because the waves of disease that passed through the Indian villages between 1815 and 1840 reduced their population from an estimated eleven thousand to just a few hundred. Waves of smallpox, measles, tuberculosis and malaria combined with environmental change caused by the fur trade and the efforts of settlers to establish Western-style agriculture in Oregon not only killed off the majority of the first Oregonians but also endangered native ways of life and put intense pressure on native cultural values and institutions that the people depended on for their survival.

The area where Portland was built in the 1840s was a meeting place for three distinct native cultures: Chinook, Kalipuya and Sahaptian. The Clearing, as the Portland town site was originally known, halfway between the important fishing grounds of Cascade Locks on the Columbia and Willamette Falls, was an important stopping place for canoes traveling between these sites. Historian Gray Whaley uses the Chinook wawa word Illahee (homeland) as the name for the complex web of Indian cultures, languages and family ties that existed before it was replaced by the Euro-American concept of Oregon. Illahee was populated by autonomous bands, usually made up of family groups, designated by the language they spoke, who traveled on regular routes during the seasons in order to gather food and other resources. Most of the native bands depended on trading with other natives in order to secure luxuries and other desirable goods.

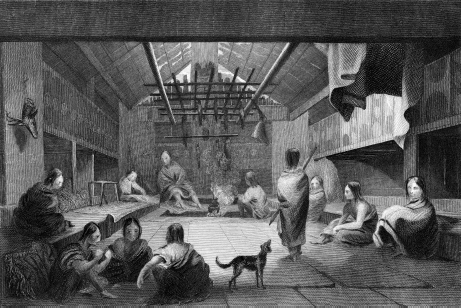

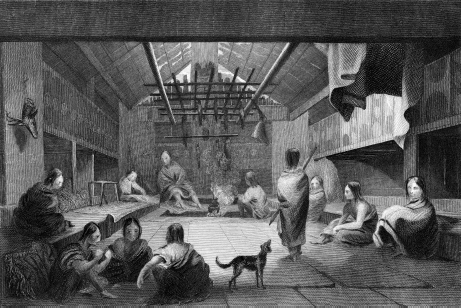

The Multnomah-speaking Chinook lived in bands of twenty to forty people in cedar longhouses along the south bank of the Columbia River. Drawing by Alfred Agate. Courtesy of Old Oregon Photos.

Language diversity was intense, with each language being divided into mutually unintelligible local dialects, causing problems of communication, cultural isolation and difficulties with trade. In response to the large diversity of language, Chinook wawa, a pidgin-style trade jargon made up of words from many languages, developed as the mutual trade language that dominated the region even after the coming of the Euro-American settlers. Chinook wawa, although limited in expressing complex ideas, provided a method for natives to trade with one another, and soon trade networks, usually based on family ties between linguistic groups, developed that brought goods from far north and south and east to the Great Plains.

The mouth of the Willamette River was dominated by Multnomah-speaking Chinook who lived in year-round villages made up of cedar longhouses. Several of these villages were situated on Sauvies Island and other strategic spots along the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia. The Willamette itself was dominated by Chinook Clackamas-speakers and Kalipuya bands speaking Tualatin and Yamhill languages. The Kalipuya traveled great distances at different seasons in order to gather food and other resources, but they usually wintered in underground lodges built near the Willamette River. Sahaptian bands, especially the Klickitat from the north side of the Columbia, also traveled to the Willamette seasonally for fishing and other food gathering. The Sahaptians, such as Nez Perce, Cayuse and Yakama, were the most nomadic of the native bands. Most Sahaptian tribes lived on the arid Columbia Plateau and were forced to travel great distances during the year in order to find enough food. The horse was introduced to the Pacific Northwest in the seventeenth century by the warlike Shoshone of the Snake River Valley, who traveled as far as Mexico in their yearly rounds and so had early contact with the Spanish. The introduction of the horse had a huge impact on the Sahaptians of the Columbia Plateau, extending the range of their travels and giving them an important military advantage. The Nez Perce, among other bands, regularly traveled over the Rocky Mountains, and their culture was greatly influenced by the Indians of the Great Plains. Guns followed the horses by a few decades, and warfare became fairly common in the northwest.

Next page