L ONG BEFORE HIS LIFE BECAME LEGEND, THE BOYS NAME WAS forgotten. Reverend Napoleon J. Gilbert scrawled it in the baptismal records of Sacred Heart Cathedral in Prince Alberta small city set on the North Saskatchewan River, where the provinces prairies meet its pines. It was the 10th baptism recorded that year. The priests pencilled cursive was hastily scribbled. In the margin of the 71st page, in the 10th volume, Napoleon wroteand misspelledthe childs name: Kizkain, John.

That day, the 27th of February in 1925, James Kiszkan and Elizabeth Jacobson had carried their sixth surviving child, their only son, through the arching red-brick faade of Sacred Heart Cathedral. They presented the three-month-old infant to the Church, dedicating him to the Catholic faith. Having immigrated from Eastern Europe and focused their best efforts on learning English, neither parent spoke French. Regardless, the reverend recorded the baptism in his preferred language. The child, he wrote, had been born le huit Novembre, 1924.

The entry was just one of thousands of church records, inside dozens of volumes of leather-bound ledgers, that sat in the back of a clerical closet at Sacred Heart for nearly a century. It was the earliest and most definitive record of the truth behind a mystery that would later baffle sportswriters and league officials for decades. But the record and the truth stayed hidden in Prince Albert, along with so much of the boys past, untouched among the stacks in Sacred Heart.

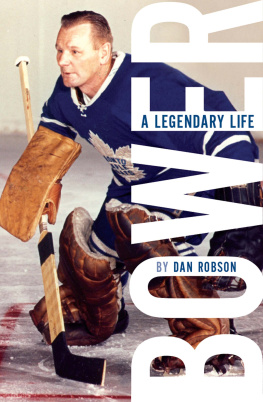

As the boy grew up, hed repeatedly change the story of his origin, twisting and turning the truth until even he wasnt quite certain of the line between fact and fiction. In fact, the fiction became inseparable from his identity. Fibs born of simple practicality or a desire for privacyor sometimes just for mischiefbecame part of his mystique, while the forgotten boy became one of the most beloved figures in hockey history. But he became much more than that too. To many he was an unmatched athletea toothless, scar-faced conqueror of time and nature. Famous for those daring poke checks and dazzling saves; for the Vezinas and the four Stanley Cup parades; for the wonder of his ageless ability, as the games oldest goalie and still a star. In later years, he became a steadfast, happy reminder of past glory for a downtrodden franchise and their many long-suffering fans. And to those who were closest, he became a faithful friend, a lovestruck husband, a tender father and a doting grandpa. As he became a legend, the boy also became a special kind of man.

That boys long journey began just beyond the doors of Sacred Heart Cathedral, around the corner at 526 Sixteenth Street West, where his familys small bungalow, its unpainted shingles faded grey, once stood. The house is long gone, replaced by a store that sells drug paraphernalia. But if you stand in the parking lot and look around, you can still see much of the world he explored beyond those doors. The barren field across the street leads to the same tracks that once carried lager from the old Molson Brewery, which still stands there today. You can picture a game of shinny on frigid winter days on the ice pad the brewery built each year, or a game of sandlot baseball by the tracks on warm summer afternoons. At the west end of the road, the old nurses quarters still stand next to where the hospital the boy was born in used to be. You can follow the streets, with a couple of turns, to find the way to Sacred Heart, where his family wore their best outfits once a week. And across the road, where a modern high school now stands, you can imagine the two-storey brick school with a small bell tower, where he used to daydream at St. Pauls middle school. The army barracks where the boy would lie about his age, hoping to go to war, still sit on the east edge of town. But the Minto hockey arena downtownwhere his unusual talent gave him his first real opportunity to become something more than he thought he could beburned to the ground long ago. Its now a parking lot.

Much of Prince Albert today traces the city as it was then, although parts have crumbled and changed with time. But pieces of the boys life are everywhere. Parts that made it into his legend, and fragments he left behind. His story is similar to many just like him, the child of immigrants in a new land, searching for a better life. The beginning is almost identical to that of the other boys and girls who called Prince Albert home. They grew up through the Great Depression, watching parents and siblings struggle to survive in an uncertain world. There was little time for dreaming through those harsh years, running towards the second global war in a quarter-century. The Stanley Cup was an unimportant fairy tale, told over scratchy airwaves on cold Saturday nights. But in some imaginations, those faraway heroes came to life as young players traced their paths along iced-over rivers and ponds. They were Charlie Conachers, Eddie Shores, Busher Jacksons and Tiny Thompsons. They used sticks and pucks made of whatever twigs and frozen droppings they could find. And they played through the blowing snow, in temperatures that often dropped to 50 below. It was cold and harshand unlikely to lead them far from lifes hard realities. But it was what their dreams were made of. Although few would ever discover where those dreams could lead, theyd find some brief respite in the carefree rush of their winter game. And that was how the story of Johnny Kiszkan begana boy on ice, slipping in his boots as he chased frozen horse dung against the prairie wind, having the time of his life.

D OWN IN THE BASEMENT OF AN OLD FIREHOUSE AT THE END of Central Avenue, on the edge of the North Saskatchewan River, are stacks of books and maps that tell the untold story of how it all began. Ken Guedo, a retired volunteer with the Prince Albert Historical Society, looks through a folder of poster-sized maps that divide the land surrounding the small city in central Saskatchewan into a grid. Guedo, in his 70s, is one of many volunteers who proudly preserve and share the history of their hometown. They are an oracle of Prince Albert knowledge. He can show you how things are now and paint a picture of how they once were: the empty parking lot that was once the magnificent Minto hockey arena, where thousands flocked each week... the Burger King where the massive Pat Burns Meat Company building once stood... the old army barracks, where Prince Albert boys signed up for war.

Guedo scans through the grids page by page, each marked by a hand-printed name. The Cummins Rural Directory Map shows the names of the people who owned homesteads in the rural reaches of Saskatchewan around the time of the First World War. He runs his finger across the page until he comes across the name hes looking forat homestead land location NW 12-50-25 W2. There he is! Guedo says. Dmytro Kiszkan. He flips through a binder with photocopy prints of other maps, showing the area cut off from the larger one hed been scanning. He finds a map that appears to be an extension of the original. The grids match up. And with the pages side by side, two squares awaytwo real-life milesis the other name hes hunting for: Jacobchuk.

Who knows if they met out there, Guedo says. I dont know. But there must be some sort of connection.

The old homestead documents offer a glimpse into how Johnny Kiszkans world came to be. Dmytro Kiszkan was just 18 years old when he left behind life as a peasant farmer, working land he didnt own, to chase the promise of new opportunities overseas. He was from a rural community known as Sniatyn, on the northeastern edge of what was the Austrian Empire, in the region of Galicianow the western edge of Ukraine. Although he was unable to speak, read or write in English, Dmytro believed his life prospects were better across the ocean than in his fractured homeland, which would soon be engulfed in humanitys greatest war.