Contents

Page List

Guide

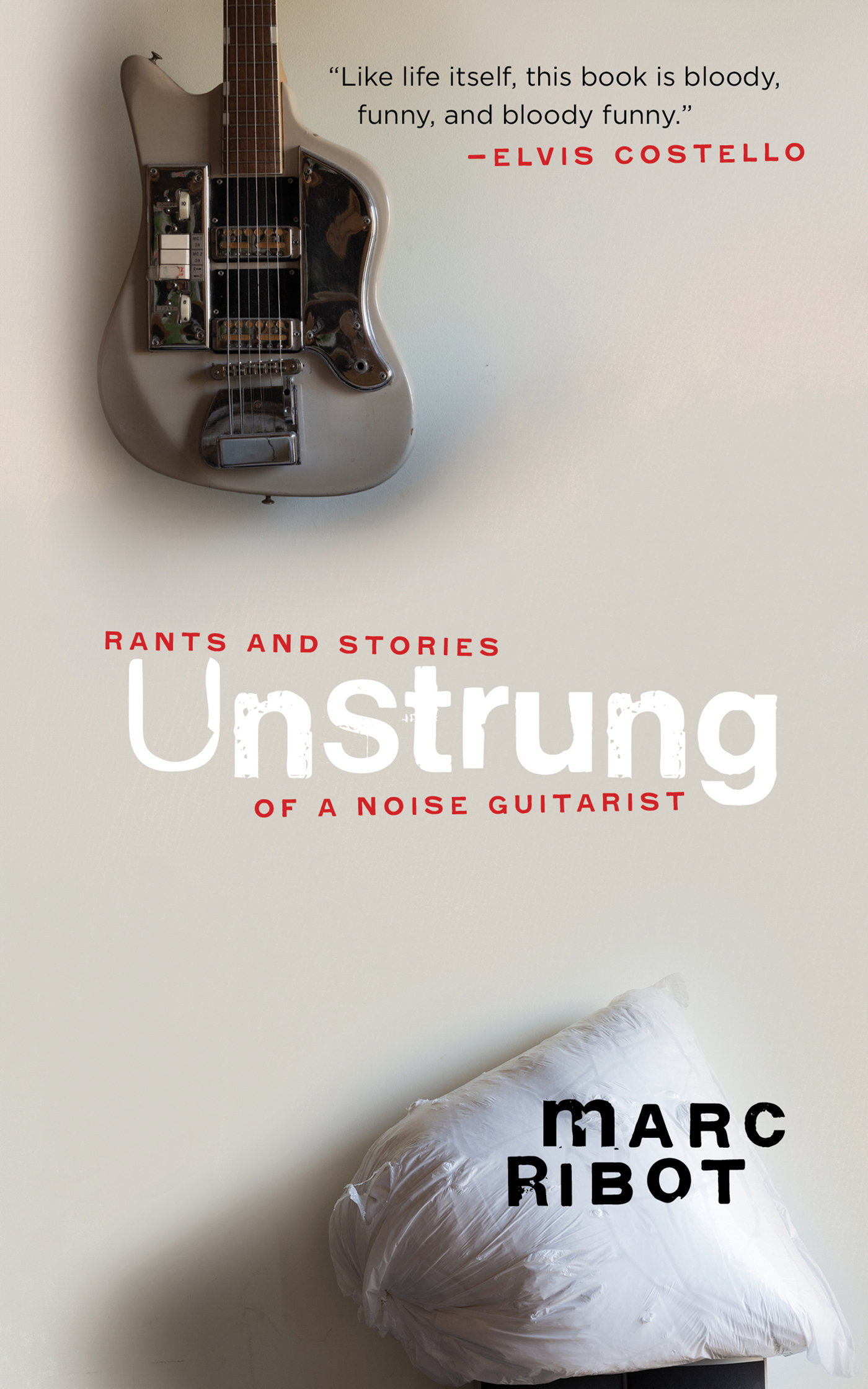

RANTS AND STORIES

UnStrung

OF A NOISE GUITARIST

RANTS AND STORIES

UnStrung

OF A NOISE GUITARIST

mARC

RIBOT

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

Published by Akashic Books

2021 Marc Ribot

ISBN: 978-161775-930-7

E-ISBN: 978-1-61775-948-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948049

All rights reserved

First printing

Akashic Books

Brooklyn, New York

Twitter: @AkashicBooks

Facebook: AkashicBooks

E-mail:

Website: www.akashicbooks.com

Table of Contents

Introduction: Ribot the Writer

by Lynne Tillman

Friends call him Ribot.

Like-minded musicians will instantly respond to Ribots stance on playing LOUD, announced in Unstrung in the first section, Lies and Distortion. Ribot writes: Im a guitarist who points extremely loud amplifiers directly at his head. He wants musicians using distorted sounds to plac[e] their amps at risk. What this risk means to him, I cant elucidate, but it is essential to his music.

Ribot is an extremist, intense in all things.

His distinction between lies and distortionmusical distortion alsois telling. No matter what subject he writes about, Ribot will also present shades of himself, his ideas, his memories. As an unreliable narrator, he cautions his readers: do not expect the impossible, absolute Truth, but proximate and fictional truths.

Like all human beings, he lives with contradictions.

Ribots stories and essays show his fierce attachment to music, which joins with his anarchistic and passionate spirit. He maintains a devoted if complicated relationship to Judaism, a rage against capitalism, and a lifelong advocacy for human rights and musicians rights. Ribot writes of fatal mistakes, is sometimes melancholic, and reckons with futility.

His belief in justice is as strong as his belief in the greatness of the late guitarist Robert Quine. An eponymous essay showcases Quines broad knowledge of music history, while Ribot catalogs their friendship, his respect for and love of Quine. We mostly talked about guitar equipment But guitar equipment, for those who love it, is a language. That kind of love runs through Ribots pieces. Nothing exists here that doesnt carry it.

He cannily converts musical ideas, a wordless language with its own vocabulary, into words. The line Quine traced through history, the qualities he looked for in used guitars and fuzz boxes, were those with the force of being to cut a wound in the numb skin of pop. The numb skin of pop kills me. Language also moves him.

Ribot credits his mentors, remembers their glory, and mourns them. He memorializes bassist Henry Grimes, who played in one of Ribots bands not long before he died. Ribots essays on classical guitarist/composer Frantz Casseus, his mentor on the guitar, and musician/producer/entrepreneur Hal Willner are elegiacal. Ribot elucidates who Willner was, what he did, and makes his death, his loss to music and more, tragic.

Ribot tells an old story about Casseus. Its the one about how composers and musicians get screwed by the music industry. Casseus was sick and old, living in a nursing home, on Medicaid, when money owed him forever finally arrived. Money never was the reason Casseus played and composed, but holding the delayed check [for $16,000] in his one good hand, Ribot writes, Casseus said to him, If I had known, I would have composed more. I felt my work to be without value.

Ribots essay on Time explains his discovery that, in transcribing tapes for Ivorian griot Emile Yoans band, the result on the sheet was different rhythmically from the groups sound. Some years later, playing in Susana Bacas group, he realized he had been completely mishearing where one was the aural signs which allow the listener to distinguish one from three, upbeat from downbeat, are culturally determined. Its true in all languages, and, in a written language, tone and rhythm are built from a complex arrangement of words, which produces meanings.

His acute and tender fictions move from old lovesMeet you downstairs was code meaning he didnt want to sleep with herto new ones, new hopes, and sorrows. Ribot exposes his vulnerability and doubts, willfully. His fine ear pushes him to write stories based on sound, on hearing, unlike any I know.

In We Tell Children the Cow Says Moo, he recounts reading to his little daughter: the rooster [says] cock-a-doodle-do. This truth drives Ribot to listen hard to an actual roosters call: As it turns out, he writes, roosters dont say cock-a-doodle do instead they emit a strange scream, punctuated into roughly three sections

His fictions survey the human comedydisappointments; the American dream turned horror movie; people losing their minds or never finding themselves, and people defeated by societys rigors and condemnations. His rhythms hit where they should.

His on-and-off-the-road stories are dedicated to honesty. O Say Can You See opens with these sentences: American life is lonely. I call you sometimes, when Im off the road. We have coffee near your stop on the N train. The trains are slower now. Most often, I dont call. Loneliness is personified in these lines.

* * *

Over the years, knowing Ribot since the 1980s, I have watched and heard him play many times, and close up. He holds his guitar close to his body, and, generally, drops his head, almost on his instrument. Hes so bent over, you cant see the guitar, so he and his guitar merge, form a new body, alive in its own world, where he wants to be. He doesnt want to see us, because he plays as much, maybe more, to hear what hes doing as he does to be heard by an audience.

Ribot writes with great care for words, for sounds. It means as much to him to get it right, and be true to it, as to his music. A good writer, like a good musician, and Ribot is both, needs to know what theyre composing to be able to understand it, maybe even do it better the next time.

Marc Ribots stories are moving and compassionate. They are revelatory, honest, and insightful, but see for yourself, and read them.

Lynne Tillman is a novelist, short story writer, and essayist. Her most recent novels are American Genius, A Comedy and Men and Apparitions. The latest short story collection, The Complete Madame Realism and Other Stories, was published by Semiotext(e). In 2022, an autobiographical, book-length essay, Mothercare, will be published by Soft Skull, and the following year, a collection of Tillmans short stories. She lives in New York with bass player David Hofstra.

Part I

LIES AND DISTORTION

Lies and Distortion

Hi. My name is Marc. Im a guitarist who points extremely loud amplifiers directly at his head. Very often. Sometimes as often as two hundred nights a year for the past forty-five years. Audiologists say this could make ones ears howl, create an uncomfortable sensation of density in ones head, and eventually make it impossible to hear human conversation. Yet I persist Why?

Its true most amps sound better at volumes loud enough to fray the edge of notes with the subtle distortion that is to electric guitars what makeup is to a drag queen of a certain age. Not accidentally, as manufacturers in the late 50s and early 60s raced to design equipment with less and less distortion, guitarists turned up louder and louder to subvert their efforts. Nor are guitarists alone in this desire to strain.