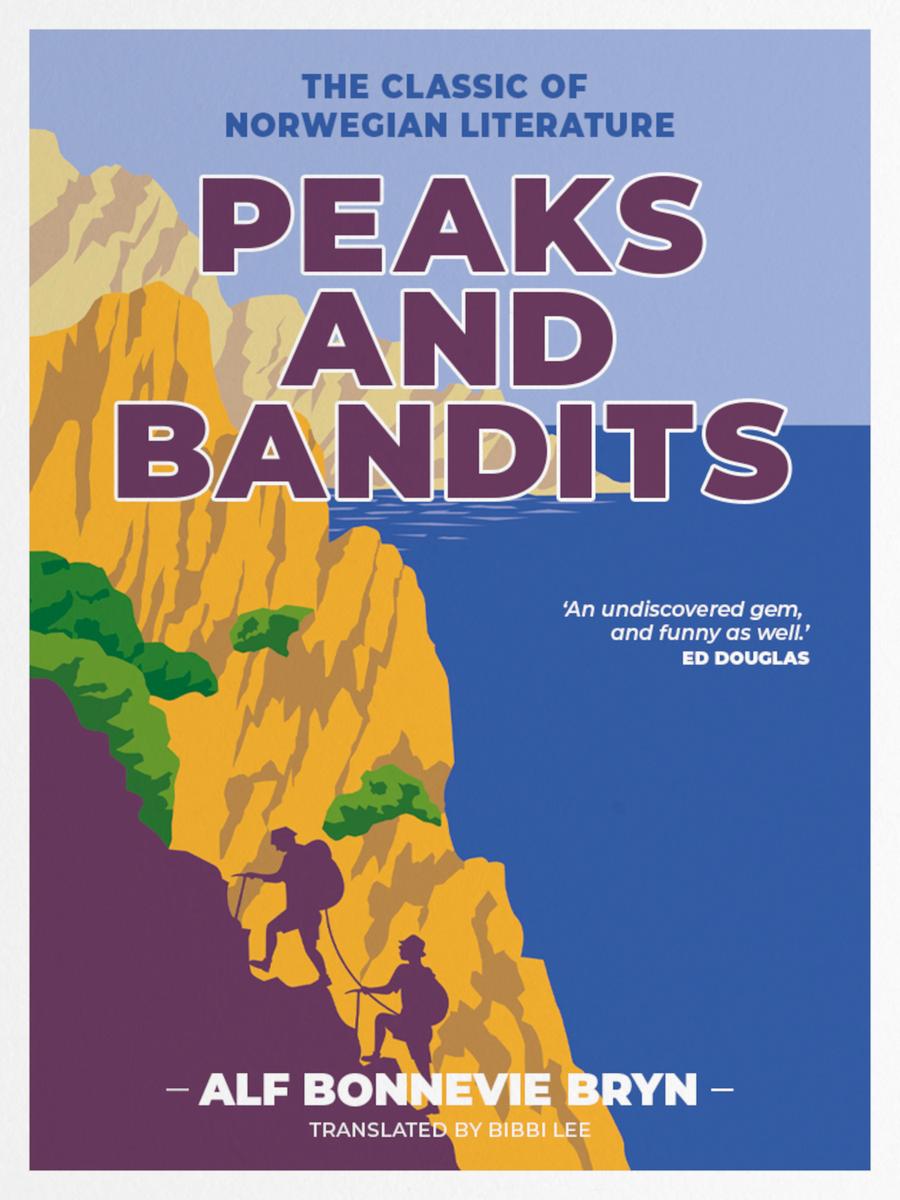

Quite late one Sunday evening in August 1909, I was hanging from a rope down the south side of Gross Ruchen.

I was hanging with my head down some eighteen to twenty-one feet under the top ridge. On the other side of the ridge, about the same distance down the north slope, hung Max van Heyden van der Slaat. Straddling the ridge right behind us sat George Ingle Finch, who was tied to the same rope. He had a big, heavy backpack with self-recording meteorological instruments on his back.

The immediate cause of finding myself in this annoying position was that a piece of the ridge, astride which Max had been edging forward, had broken off and sailed down along with Max. To prevent all three of us from going the same way, I had slid down the south side and flipped around as the rope tightened. This, incidentally, is an example of the regular procedure in this kind of situation. I knew this from the literature, but it was the first time I had personally used the technique.

It seemed quite frightening. The first time at any rate. A feeling somewhat like letting oneself go off a high ski jump, or diving into cold water from a great height. Its just that, as a rule, one has more of an opportunity to get used to those things. Parachuting out of airplanes was not in vogue then, or else that would have been the closest comparison.

It has been said that in those apparently life-threatening moments, your whole life passes before you in the blink of an eye. Childhood memories and your home appear, and you regret things you have done or failed to do. This does not tally with my experiences. The only thing I can remember thinking of as I rushed down the wall of ice was whether Max was solidly tied to the rope. Not that I was particularly worried about his fate, but he did have the vitally important task of being the counterweight and obstacle to my continuing journey. Thank God Max was sitting firmly and the rope held.

Considerably worse, or much more exciting anyway, was the case of O.G. Jones who climbed Dent Blanche in 1887 with his friend (or so he thought) Dr H. Robinson. They had left Zermatt the day before to ascend Dent Blanche by a particularly difficult route, which for some reason had acquired the name Arte des Quatre nes (The Four Donkeys Ridge). As you approach the summit of Dent Blanche, the landscape looks about the same as the ridge toward the top of Gross Ruchen, the only difference being that the elevation is considerably higher and the north face practically sheer for the first 900 to 1,200 feet. Then it gradually becomes a slick ice wall, which after a while slopes off and ends in a glacier about 4,500 feet below the summit. The drop on the south side is almost equally high but not quite so steep.

A mean wind was blowing with quite a bit of snowdrift, and Jones could barely see Robinson, who was walking about forty-five feet ahead of him on the rope. He saw Robinson lose his footing and begin to slide, after which he turned himself outward and disappeared. This was due to Robinson having untied himself from the rope before he slid, so that Jones took all the rope with him on the rest of his journey down. Robinson managed to stop his slide with the help of his ice axe and remained on the top of the ridge.

What Jones did not know was that his friend had just discovered that he had been having a relationship with Mrs Robinson for some time something that in the bigoted, bourgeois English circles of the day was regarded as being against good form.

Robinson had a tough time getting back down from the top of Dent Blanche. He had to spend two nights in the open and arrived in Zermatt extremely bedraggled, but pleased to have saved the family honour in such a clever way.

In a cafe in Zermatt he found his friend Jones and Mrs Robinson fortifying themselves with a cup of tea after having spent a successful night in a hotel. It turned out that Jones had made it, without a scratch, from the top ridge of Dent Blanche down to the glacier 4,500 feet below, with the help of a big avalanche. He had been a little confused but had regained consciousness on the glacier, and then spent the night in a cabin not far away before walking down to Zermatt. After organising the rescue operation for his friend left behind, he could in good conscience turn his attention to what he took to be the widow.

This story is recorded (minus some of the details and explanations I have provided) in the Alpine Journal of 1888. Though there is nothing to indicate how family relations developed from then on.

Complications of the RobinsonJones kind did not exist between Max and me we were both unmarried. Besides, it wasnt Max who had planned the trip; on the contrary, it was with some reluctance that he had come along on the ascent, his first (and probably also his last).

Max van Heyden van der Slaat was not Dutch, as his name would suggest. In his youth his father had moved to Russia, where he had made a huge fortune and was the owner of one of the countrys biggest rubber factories and a number of forest properties, among other things. But Max was no plutocrats son. He frequented shady characters and became a member of revolutionary student circles. As this corresponded badly with his fathers business interests, he sent Max to Zurich to study. He sent him away with an elderly servant and a million francs, meant to last the entire duration of study.

Of all the cities in Europe at that time Zurich was the worst choice for someone meant to be kept away from dawning Bolshevism. It was there that the organisation which would eight years later become the revolution was formed. And it was there that Ulyanov sat in his lodgings or his favourite pub lecturing about Marx, Engels and himself to an ever-larger circle of male and female admirers.

On the periphery of this circle hovered Max, who very quickly put his studies aside in order to dedicate himself to a niece of the Russian painter Vereshchagin a relationship that nonetheless gave him more sorrow than joy. So it was her fault that Max was hanging where he was.

The previous history was this: one evening I was at a small and simple variety theatre watching a performance by professional boxers. As far as I can remember, the match was between the Battling Kid, champion of Missouri, and Pete, the Terror of Milwaukee, who were giving a very average demonstration of the noble art. After the act, the director came on stage and announced an award of 100 francs to anyone in the audience who could hold his own for three minutes against one of the professionals.

For a long time this had been a popular additional act, something akin to what circuses do when they invite the public to come and stand on the broad back of a horse which is trained to wiggle a little so that the victim is thrown off, to everyones amusement. But lately the number of volunteer amateur boxers had dwindled, and you had to be satisfied with hired victims who would let themselves be knocked out in a gentle fashion once per evening.

This time, however, we were luckier. A tall, skinny, light-haired youngster calmly rose from his seat in the first row, stepped across the orchestra pit and presented himself. That was the first time I made Georges acquaintance. It was also the first time for the Terror of Milwaukee, and for him it was a sad experience.

The fight didnt last a full minute. When Terror hit the floor for the third time, he refused to get up. Poor Terror didnt stand a chance. Georges arms were six inches longer than his and he never reached farther than Georges left or right glove. He couldnt even sneak in a clinch, every professional boxers friend and helper when in need. George humbly received the roaring ovation and asked if the Battling Kid didnt also want to go one round. The Battling Kid didnt want to. But then came the great anticlimax: George wasnt paid. No, the deal was for three minutes, this had lasted only one, so no 100 francs. The public probably missed a lot when the discussion between George and the variety show administrators took place behind closed doors.