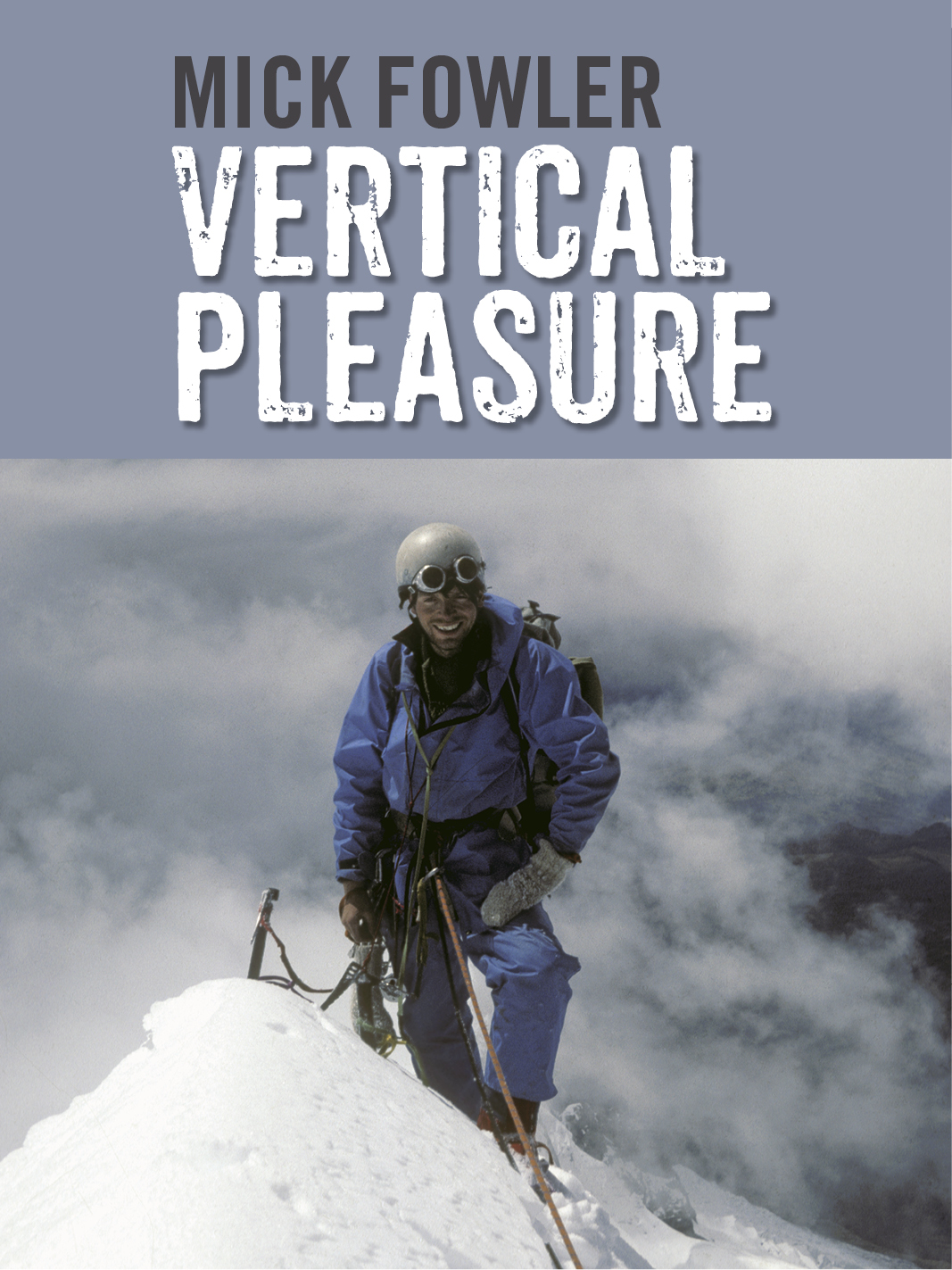

The author wishes to thank George Fowler, Victor Saunders, and Chris Watts for use of photos noted by initials in the captions. The maps were drawn by Martin Collins.

A strong and irresistible feeling of modesty now invaded each individual of the party, and no one would consent to accept the usually coveted distinction of descending as last man. This humility of mind seeming wholly proof to the blandishments of the most artful flattery, we had to seek another method of grappling with the difficulty.

On the inside of the flake and about six feet below us, was a small ledge from which it appeared that a staircase might be constructed leading obliquely down the crevasse. It emerged beyond the edge of the flake at the level of the low snowfield. Whether it would be possible to cross the schrund at this point was not very certain, but in mountaineering something should always be left to luck. It adds such zest and interest to the proceedings!

A.F. MUMMERY

Chapter One

Education with George

Struggles with the Boa Constrictor Beetham routes in Borrowdale our fall in Stanger Ghyll diarrhoea in the Bertol Hut Rothorn, Dom, Monte Rosa and other 4000m peaks discos on Saturdays, Harrisons on Sundays with Morrison and Stevenson my first minivan

Poor Ian was never really a climber; in fact he was never really an outdoor enthusiast at all. My grandmother always assured me (much to my irritation) that he had fine limbs but this alone seemed not to be a qualification for enjoying a life grappling with the joys of nature. Personally I felt he had rather fat limbs and, being a somewhat precocious child, never tired of saying so. I had however been close friends with Ian since nursery days. He was a ginger tousle-haired child with a mischievous sense of humour reminiscent of William in Richmal Cromptons books. Although we ended up at different schools our friendship continued in the holidays and our early adventures tended to be planned together. As those consisted of exploring the local sewage system or cycling at night (without lights) up the M1, George, my father, felt that perhaps a rather more hygienic and less dangerous pastime was called for.

He had always had an interest in the outdoors, but living in the rather rundown North London suburb of Harlesden with no car had been a major handicap which consigned escape to the hills to his annual holidays from the printers where he worked. Finances were also a problem. Pre-war expeditions to the Alps tended to be on a one-off basis and trips further afield were definitely out.

Ironically, as was the case with many British servicemen, it was the 1939-45 war which was to give him the opportunity to visit other parts of the world and to develop his love of exploration, other cultures and, most importantly for me, mountain environments. In retrospect he was perhaps rather fortunate to have survived the war and in fact seems to have had rather a good time. Despite volunteering for front-line duties at various intervals, his most memorably unpleasant experience was digging up an old toilet area with his bare hands whilst trying to fashion a pillow out of North African sand dune many miles away from the nearest water supply. This left a marked impression (and odour) and distinctly spoiled his war until a combination of poor eyesight in one eye and good fortune saw him being posted to South Africa where the Drakensberg mountains provided unlimited recreational possibilities in what appeared to be unlimited recreation time. A subsequent stint in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and then northern India gave him a more varied diet of outdoor pleasure and a distant first sight of Everest.

The bug had bitten, so to speak, but it was to be thirty-five years before he would see the Himalayan giants again. Marriage to my mother immediately after the war was followed by much hill-walking in Britain and, the highlight of this era, a guided walk up the Allalinhorn (4027m) near Zermatt. My arrival in 1956 put a brake on such extravagances. Then my mothers sudden illness and tragic death in 1959, followed almost immediately by my fathers redundancy from a supposedly secure job, were hardly events likely to result in a surge in recreational activity.

My grandmother moved in, ostensibly to replace my mother as best she could, and gradually Georges enthusiasms came to the fore once more. Along with Arthur and Tony, a couple of friends of his from the printing trade, he used to pay intermittent visits to the sandstone outcrops around Tunbridge Wells, with me continually pestering him to include the eight-year-old Fowler body in such activities. Initially he was reluctant, but as our childhood games became increasingly dangerous the time came when it was clearly safer for us to be engrossed in vertical excitement under the parental wing rather than being left to our own devices.

There was, however, one final obstacle to the start of my climbing career my fathers Reliant Supervan Mark III. I could never understand why he insisted on being the proud owner of one of these vehicles and took delight in emphasising the camaraderie involved in waving to fellow Reliant three-wheeler owners. This vehicle was the overriding embarrassment of my schooldays and I would spend hours dreaming up schemes to avoid being seen anywhere in it. Those few friends who knew of the vehicles existence referred to it disparagingly as the Spazwagon, a name which I always felt to be eminently suitable.

It was a sort of putrid blue colour Aztec blue was, I believe, the exact tone. Having no interior lining, it was possible to see the ribs and veins of the fibreglass and get the feeling of being truly at one with the road, or exposed to the elements, depending on ones interpretation. Almost overriding the fibreglass factor was the lack of a fourth wheel. My father assured me that this was a good point in that it saved money by allowing him to tax the vehicle as a motorbike and drive it on a motorbike licence. Personally I tended to notice more its unnerving habit of lurching round corners.

Altogether I felt it was a rather inauspicious vehicle in which to start my climbing career. Thus there was nothing else for it but to start climbing either on my own or with someone from the small circle of friends who already knew of the Spazwagons existence.

Ian expressed the most interest and was duly persuaded to join me. It is true to say that he did not really possess a rock-climbers physique. I was soon to discover that having fine limbs compared to my thin scrawny ones (my grandmother again) did not seem to be an advantage when grappling in the depths of narrow slimy rock chimneys in the sandstone outcrops just south of London. The choice of my first climbing experience was in the hands of my father and so I suppose he can be held responsible for Ian not exactly taking to the sport in a very enthusiastic or effective manner