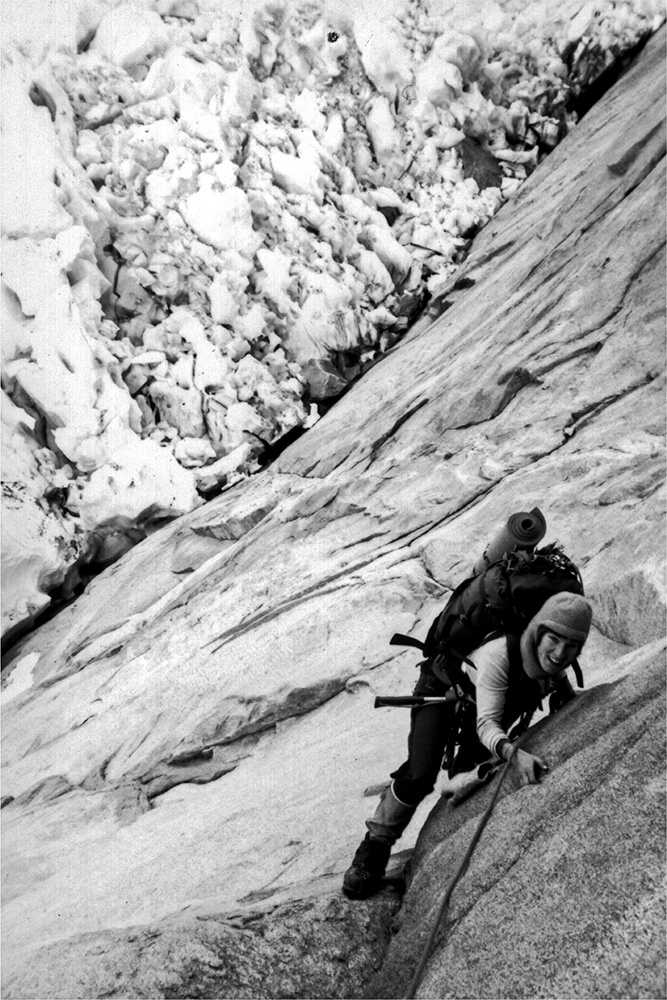

Gordy Skoog atop Mount Formidable making the first winter ascent, 1981 (Photo by Lowell Skoog)

INTRODUCTION

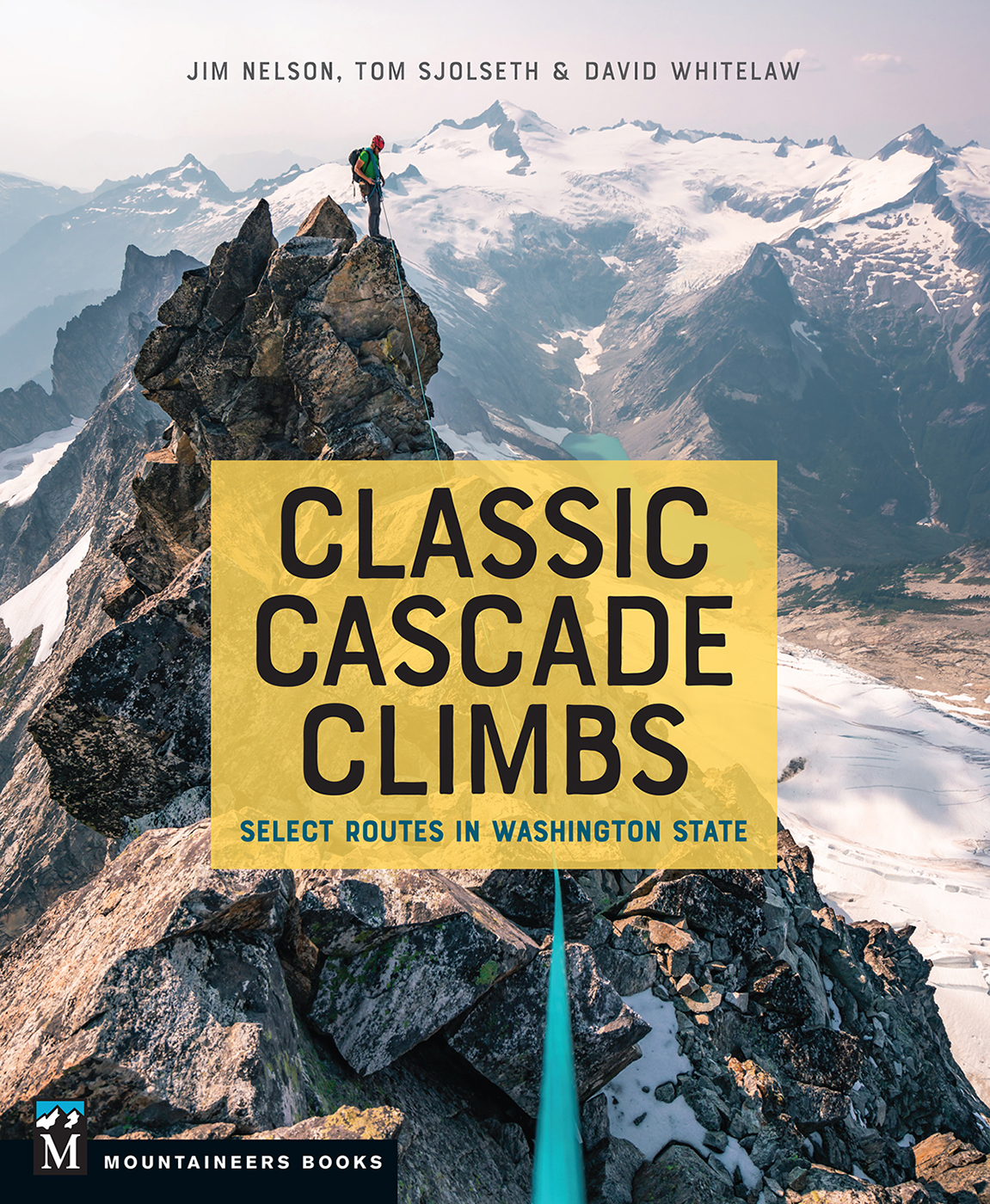

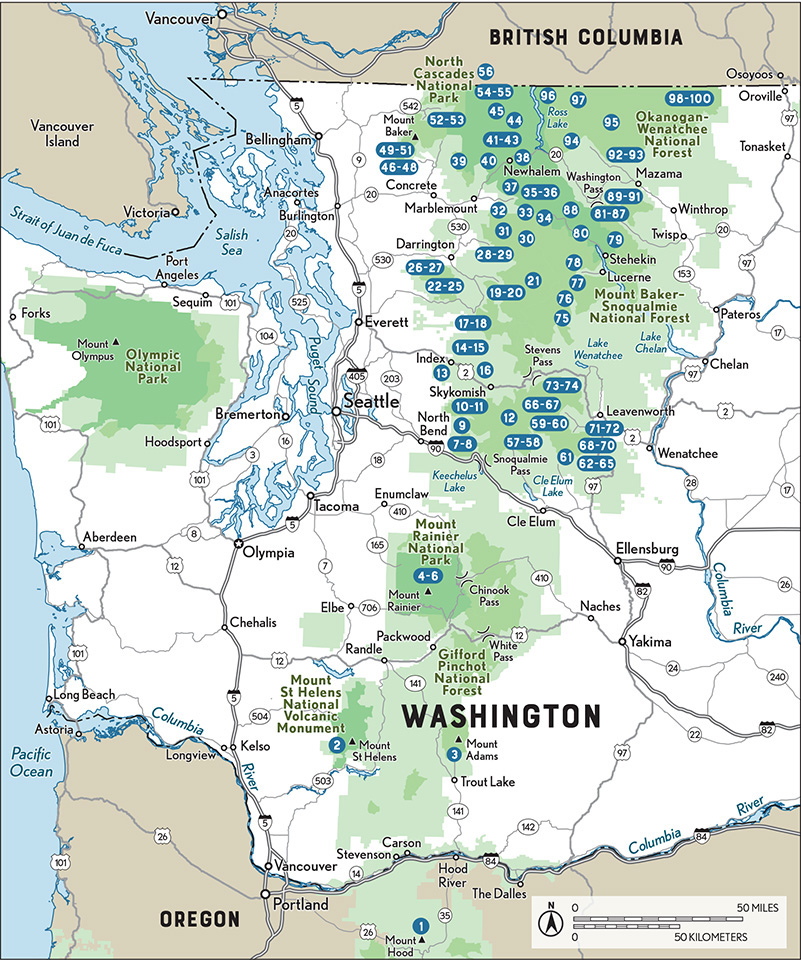

Washington State! A green Pacific paradise of grand scope and opportunity. Time and geology have created a region of unparalleled beauty and continuous variety. It is a climbers paradise, to be certain, and nearly every corner of the state offers some kind of prize, large or small, famous or forgotten. There are deep and endless canyons of granite, many miles of basalt pillars and cracks, incredible alpine rock climbs, and always the awesome snow domes of the volcanoes.

From the ice-clad summit of Mount Rainier to the hot granite of Tumwater Canyon, there is legendary climbing here of every type, for every season, and at every grade. Whether you are just visiting or lucky enough to call this place home, looking for camaraderie or solitude, seeking exploration or classic climbs, we hope our suggestions will provide just what you want.

Weve all heard the smack-talk about the rain, and inevitably some trips will change in character as a result. The truth is, however, still fairly simple: the summers are simply incredible. Between the equinoxes, from the middle of June to the beginning of September, there is often negligible precip, and most of the climbs described in this volume will be in great shape. Lowland rock climbing in eastern Washington, sheltered from Pacific storms by the great shower curtain of the Cascades, is often possible from March to November. And plenty of climbing is done in the winter, too.

Washington has been called home by a long and distinguished list of inspirational climbers, from Lage Wernstedt and Hermann Ulrichs to John Roper and Colin Haley. For those with the inclination and imagination, there remain many lifetimes of new and unclimbed routes to be dreamed and realized. Some will merely pass through Seattle on the road between Yosemite and Squamish; for others, those great locations will seem wonderful training grounds for the real business of state: Washington State.

Peaks of the Northern Pickets from the southwest, with Phantom Peak in the center; left from Phantom are Ghost Peak, Crooked Thumb, and the Challengers. Mount Redoubt is behind Challenger; the distant peak left of center is Mount Spickard. (Photo by John Scurlock)

VOLCANO HISTORY

Indigenous peoples have inhabited the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years and developed their own myths and legends about the Cascades. In these legends, St. Helens, with its pre-1980 graceful appearance, was regarded as a beautiful maiden over whom Hood and Adams feuded. Native tribes also had their own names for many of the peaks: Tahoma, the Lushootseed name for Mount Rainier; Koma Kulshan or simply Kulshan for Mount Baker; Louwala-Clough or Loowit, meaning smoking mountain, for Mount St. Helens.

In 1792 British navigator George Vancouver explored Puget Sound and gave English names to the high mountains he saw. Mount Baker was named for Vancouvers third lieutenant, Joseph Baker; Mount Rainier was named after Admiral Peter Rainier. Vancouver named Mount Hood after Lord Samuel Hood, an admiral of the Royal Navy. Mount St. Helens was named for Alleyne FitzHerbert, first Baron St. Helens, a British diplomat.

In 1805 the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through the Cascades on the Columbia River, which for many years was the only practical route through that part of the range. Looking at Mount Adams, they thought it was Mount St. Helens. When they later saw Mount St. Helens, they thought it was Mount Rainier. The Lewis and Clark Expedition, and the many settlers who followed, met the last obstacle on their journey at the Cascades Rapids in the Columbia River Gorge. Before long, the whitecapped mountains that loomed above the rapids were called the mountains by the cascades, and later simply the Cascades. The earliest use of the name Cascade Range is found in the writings of botanist David Douglas.

THE CASCADES

The amazing scope of the Cascades makes it difficult to characterize the range in any all-encompassing way. Its changing geology, swirling weather, and overall size all provide a variety of choices as well as a variety of conditions.

In general, the Cascades rise from relatively low footings in the south, and the southern interests in this book are with the volcanoesMounts Hood, Adams, St. Helens, and Rainier. In the central region of Washington State, between Snoqualmie Pass and the Boulder River, the range takes on a more jagged uplift of nonvolcanic and largely nongranitic peaks like The Tooth, Mount Garfield, and Mount Index. This central region also has several well-known granitic intrusions like the Stuart Range and the Darrington group as well as others. Finally, in the 80 miles or so of the northernmost part of the state, fabled summits like Liberty Bell, Forbidden Peak, Bear Mountain, and Slesse Mountain make for a dramatic climax to the range and are a profound lure for climbers. It is still the most wild and rugged of the regions described in these pages.