UNDER THE WIRE

UNDER THE WIRE

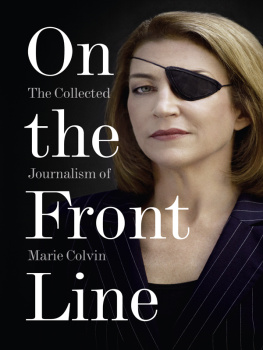

Marie Colvins Final Assignment

Paul Conroy

WEINSTEIN

BOOKS

Copyright 2013 by Paul Conroy

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the Publisher. For information address Weinstein Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

First published in Great Britain 2013

Editorial production by Marrathon Production Services, www.marrathon.net

Typesetting by Ellen Rosenblatt/SD Designs, LLC.

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-1-60286-237-1 (e-book)

Published by Weinstein Books

A member of the Perseus Books Group

www.weinsteinbooks.com

Weinstein Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

First U.S. edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of

Marie Colvin, Remi Ochlik, Neil Conroy and the 72,305 Syrians

reported dead at the time of writing.

Thank you in as near to alphabetical order as possible.

My parents, Joan and Les Conroy; Jenny and Alan Conroy; Kate, Max, Kim and Otto Conroy; Abu Hanin and the media crew in Baba Amr; Abu Lailah; Dr. Ali in Baba Amr; Annabelle Whitestone; Arwa; Assif; Bonnie Hardy; Bryan Denton; Dolores and all the staff at London Bridge Hospital; Edith Bouvier; Ella Flaye; Dr. Hakim; Javier Espinosa; John Witherow; Joss Stone; Maher; Miles; Dr. Mohamed Al-Mohamed; Parri; Razan; Ray Wells; Richard Flaye; Rola; Salah; Sean Ryan; Tom Fletcher and family; the unknown smugglers; The Vet; Wael; William Daniels; Zara; the Farouk brigade of the FSA; Neil and Tim of CNN; Annabel, Laura and Tim at Peters Fraser and Dunlop; Richard Milner and Josh Ireland at Quercus; the Sunday Times, News International and all of my colleagues who rallied to my support during my recovery; all of my Twitter friends.

The people of Syria.

CONTENTS

March 18, 2003, Qamishli, Syria

The boat seemed ridiculously out of place in the tiny hotel room. I looked at the four large truck inner tubes lying on the floor, lashed together with bits of rope and wood. Id even added luggage straps for my camera kit (gear). Now, after days spent slaving over it, my home-made raft was finally ready to be deflated and transported to its launch site the west bank of Syrias Tigris river. The boats mission: a one-way voyage from Syria to northern Iraq. I stared out of the window of the shabby hotel room and absorbed the empty vista desert, miles of unbroken desert. I looked back at the boat. It seemed more incongruous than ever.

It was a boat born of desperation. As America and its allies prepared to invade Iraq, the worlds press corps, sensing a televisual bonanza, began to gather at strategic crossing points along the Iraqi border. I had chosen to cross into Saddam Husseins doomed state via northern Syria. Once inside, I planned to link up with a battle-hardened bunch of Kurdish rebels known as the Peshmerga and then follow them as they advanced south towards Baghdad from their mountainous stronghold in the north. There was, however, a slight hitch: I needed permission from the Syrian regimes ruthless intelligence service to cross the river border into Iraq. As the drum roll of the Iraq war intensified, Syrias secret police dug their heels in. Three weeks passed and still the Mukhabarat refused to give us permission to cross.

The wait would have been bearable if only the Syrian border town of Qamishli the desert outpost that lies on the crossroads between Iraq, Turkey and Syria hadnt been one of the least salubrious places in which to be stuck. There were no bars, no restaurants and, by now, there was virtually no hope of receiving the fabled piece of paper that would permit a crossing into the Kurdish-held parts of northern Iraq.

To add to the boredom, everything had begun to grow depressingly familiar. Every day for weeks on end between twenty and thirty lethargic journalists would drag themselves out of bed and traipse over to the intelligence service headquarters five hundred meters down the road from the hotel. We would be ushered into an office, told to sit down and given glasses of hot tea. After an hour or so an expressionless officer would enter the room. Hed shake his head and announce with a hint of hostility that, once again, wed been denied permission to enter Iraq. The group of increasingly crestfallen journalists would slowly shuffle back to the delightfully named Petroleum Hotel, where the facilities, rather sadly, lived up to the hotels name.

And so it was that we had become trapped, tantalizingly out of reach of the battle that wed come to cover and stuck in what appeared to be an unfinished, downmarket version of a British Travelodge, built in the desert.

The intelligence headquarters had once been a family home, but all signs of coziness and domesticity had long since been removed. In place of family portraits were the badly printed photographs of men wanted by the Syrian authorities. It now looked more like a committee room from Stalinist Russia. The boredom and nervous frustration of the past few weeks were visible on the faces of my fellow journalists, who sat and drank tea listlessly, waiting for something, anything to happen.

I remember one particularly tedious day when the small room was near full to bursting. Journalists who were unable to find a seat on the sofa or the armchairs sat on cushions on the floor, while others dribbled down their chins and struggled with wobbly-neck syndrome to stay conscious. Suddenly the door crashed open on this scene of total lassitude. A lone female appeared, wearing a battered brown suede jacket and with a black eyepatch covering her left eye. She stood stock still in the doorway and surveyed the room with a smooth, feline movement of her head. She paused as she absorbed the motley bunch of comatose journalists in front of her.

My God, theyre drugging the fucking journalists. They must be drugging the tea, she exclaimed in absolute disgust. And that was it. She never said anything else. She just turned on her heel and left the room.

Some of the journalists couldnt even muster the energy to look up at her, so deep was their stupor. A few managed to turn their heads but only to blink in her general direction. That was my first sighting of the legendary Marie Colvin.

As the ritual disappointment of the Mukhabarat office began to take its toll, all my plans to cross into Iraq and link up with rebel fighters seemed doomed to fail. It was time to act. And so it was, as I watched the lifeblood begin to drain from the journalists gathered in the Petroleum Hotel, that the idea of the boat was born.

My partners in crime for the boat project were Norwegian filmmaker Paul Refsdal, a young New York Times stringer called Liz and a Kurdish cab driver called Ali. I put Ali in charge of procuring the necessary boat-building materials. He would also act as chief smuggler to get us through the Syrian military positions strung out along the river. We needed the inner tubes of truck tires, rope, wood, netting and handpumps, all of which Ali acquired with amazing speed from the backstreet workshops of Qamishli.

Ali was a superstar. Clad at all times in a bright mustard-colored tracksuit made from synthetic fibers visible from the moon his eyes lit up and sparkled like a little boys when I told him about the boat plan. Kurds like Ali in the Qamishli region had suffered heavily at the hands of the Syrian regime. I guess Ali saw the smuggling operation as a small way of hitting back, of getting one over on Syrian intelligence.

Next page