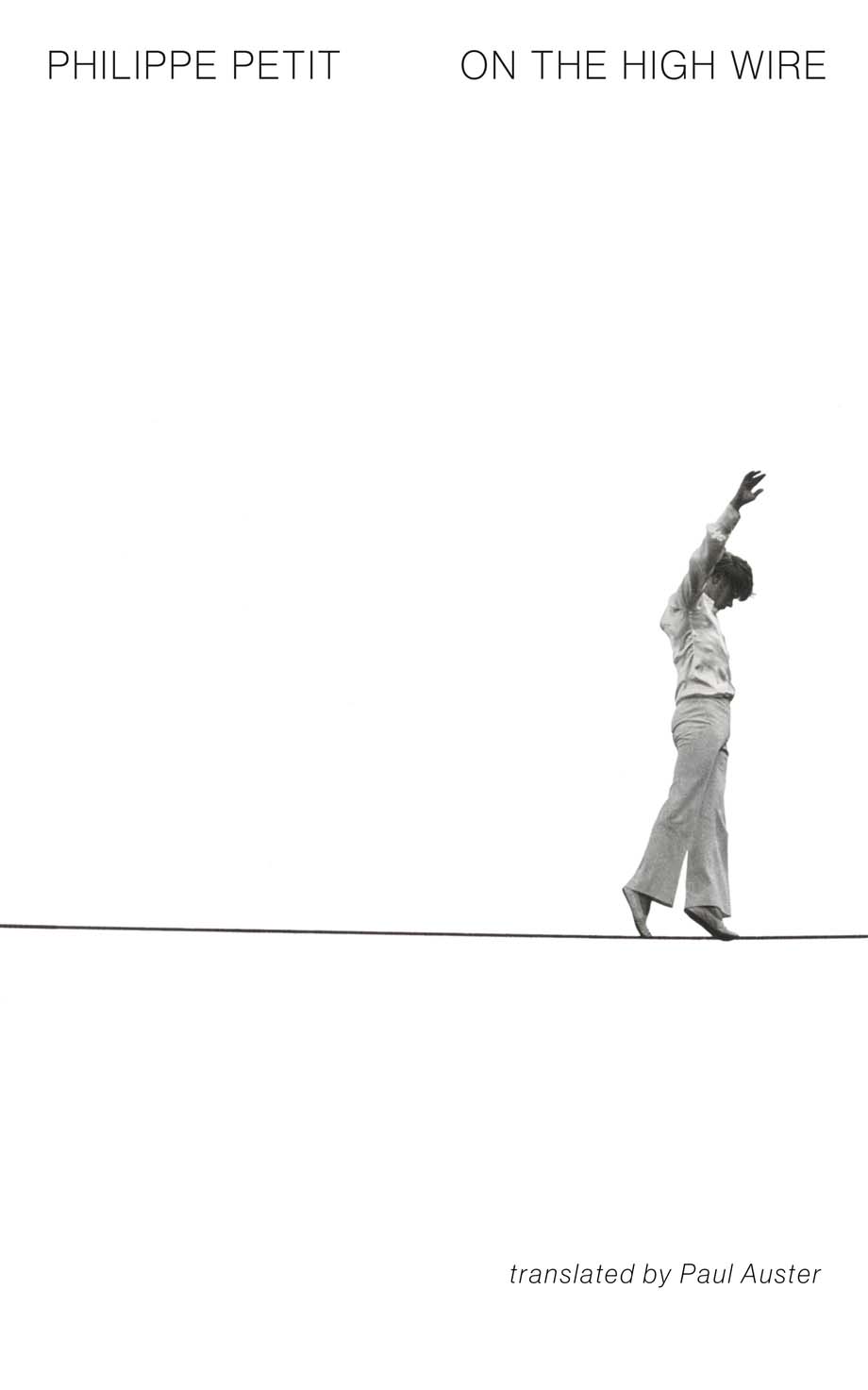

On the High Wire

Also by Philippe Petit

Trois Coups

Funambule

Trait du funambulisme

To Reach the Clouds

(also published as Man On Wire and The Walk)

Lart du pickpocket

A Square Peg [unpublished]

Cheating the Impossible

Why Knot?

Creativity, the Perfect Crime

Copyright 1985 by Philippe Petit

Introduction copyright 1982 by Paul Auster

Copyright 2019 by New Directions Publishing Corp.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

On the High Wire was originally published by Random House, Inc.

The introduction was originally published in The Art of Hunger, Sun and Moon Press

First published as New Directions Paperbook 1450 in 2019

Manufactured in the United States of America

Design by Erik Rieselbach

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Petit, Philippe, 1949 author. | Auster, Paul, 1947 translator, author of introduction.

Title: On the high wire / Philippe Petit ; translated, with an introduction, by Paul Auster.

Other titles: Trait du funambulisme. English

Description: New York : New Directions Books, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019007707 | ISBN 9780811228640 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Tightrope walking.

Classification: LCC GV553 .P4713 2019 | DDC 796.46dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/201900770

eISBN: 9780811228657

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

introduction

I first crossed paths with Philippe Petit in 1971. I was in Paris, walking down the Boulevard Montparnasse, when I came upon a large circle of people standing silently on the sidewalk. It seemed clear that something was happening inside that circle, and I wanted to know what it was. I elbowed my way past several onlookers, stood on my toes, and caught sight of a smallish young man in the center. Everything he wore was black: his shoes, his pants, his shirt, even the battered silk top hat he wore on his head. The hair jutting out from under the hat was a light red-blond, and the face below it was so pale, so devoid of color, that at first I thought he was in whiteface.

The young man juggled, rode a unicycle, performed little magic tricks. He juggled rubber balls, wooden clubs, and burning torches, both standing on the ground and sitting on his one-wheeler, moving from one thing to the next without interruption. To my surprise, he did all this in silence. A chalk circle had been drawn on the sidewalk, and scrupulously keeping any of the spectators from entering that space with a persuasive mimes gesture he went through his performance with such ferocity and intelligence that it was impossible to stop watching.

Unlike other street performers, he did not play to the crowd. Rather, it was as if he had allowed the audience to share in the workings of his thoughts, had made us privy to some deep, inarticulate obsession within him. Yet there was nothing overtly personal about what he did. Everything was revealed metaphorically, as if at one remove, through the medium of the performance. His juggling was precise and self-involved, like some conversation he was holding with himself. He elaborated the most complex combinations, intricate mathematical patterns, arabesques of nonsensical beauty, while at the same time keeping his gestures as simple as possible. Through it all, he managed to radiate a hypnotic charm, oscillating somewhere between demon and clown. No one said a word. It was as though his silence were a command for others to be silent as well. The crowd watched, and after the performance was over, everyone put money in the hat. I realized that I had never seen anything like it before.

The next time I crossed paths with Philippe Petit was several weeks later. It was late at night perhaps one or two in the morning and I was walking along a quai of the Seine not far from Notre Dame. Suddenly, across the street, I spotted several young people moving quickly through the darkness. They were carrying ropes, cables, tools, and heavy satchels. Curious as ever, I kept pace with them from my side of the street and recognized one of them as the juggler from the Boulevard Montparnasse. I knew immediately that something was going to happen. But I could not begin to imagine what it was.

The next day, on the front page of the International Herald Tribune, I got my answer. A young man had strung a wire between the towers of Notre Dame Cathedral and walked and juggled and danced on it for three hours, astounding the crowds of people below. No one knew how he had rigged up his wire nor how he had managed to elude the attention of the authorities. Upon returning to the ground, he had been arrested, charged with disturbing the peace and sundry other offenses. It was in this article that I first learned his name: Philippe Petit. There was not the slightest doubt in my mind that he and the juggler were the same person.

This Notre Dame escapade made a deep impression on me, and I continued to think about it over the years that followed. Each time I walked past Notre Dame, I kept seeing the photograph that had been published in the newspaper: an almost invisible wire stretched between the enormous towers of the cathedral, and there, right in the middle, as if suspended magically in space, the tiniest of human figures, a dot of life against the sky. It was impossible for me not to add this remembered image to the actual cathedral before my eyes, as if this old monument of Paris, built so long ago to the glory of God, had been transformed into something else. But what? It was difficult for me to say. Into something more human, perhaps. As though its stones now bore the mark of a man. And yet, there was no real mark. I had made the mark with my own mind, and it existed only in memory. And yet, the evidence was irrefutable: my perception of Paris had changed. I no longer saw it in the same way.

It is, of course, an extraordinary thing to walk on a wire so high off the ground. To see someone do this triggers an almost palpable excitement in us. In fact, given the necessary courage and skill, there are probably few people who would not want to do it themselves. And yet, the art of high-wire walking has never been taken seriously. Because wire walking generally takes place in the circus, it is automatically assigned marginal status. The circus, after all, is for children, and what do children know about art? We grownups have more important things to think about. There is the art of music, the art of painting, the art of sculpture, the art of poetry, the art of prose, the art of theater, the art of dancing, the art of cooking, the art of living. But the art of high-wire walking? The very term seems laughable. If people stop to think about the high wire at all, they usually categorize it as some minor form of athletics.

There is, too, the problem of showmanship. I mean the crazy stunts, the vulgar self-promotion, the hunger for publicity that is everywhere around us. We live in an age when people seem willing to do anything for a little attention. And the public accepts this, granting notoriety or fame to anyone brave enough or foolish enough to make the effort. As a general rule, the more dangerous the stunt, the greater the recognition. Cross the ocean in a bathtub, vault forty burning barrels on a motorcycle, dive into the East River from the top of the Brooklyn Bridge, and you are sure to get your name in the newspapers, maybe even an interview on a talk show. The idiocy of these antics is obvious. Id much rather spend my time watching my son ride his bicycle, training wheels and all.