Table of Contents

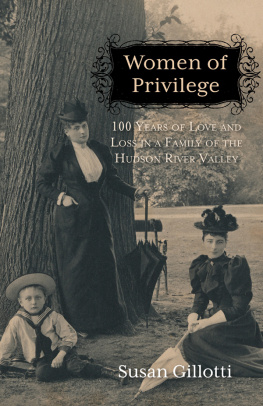

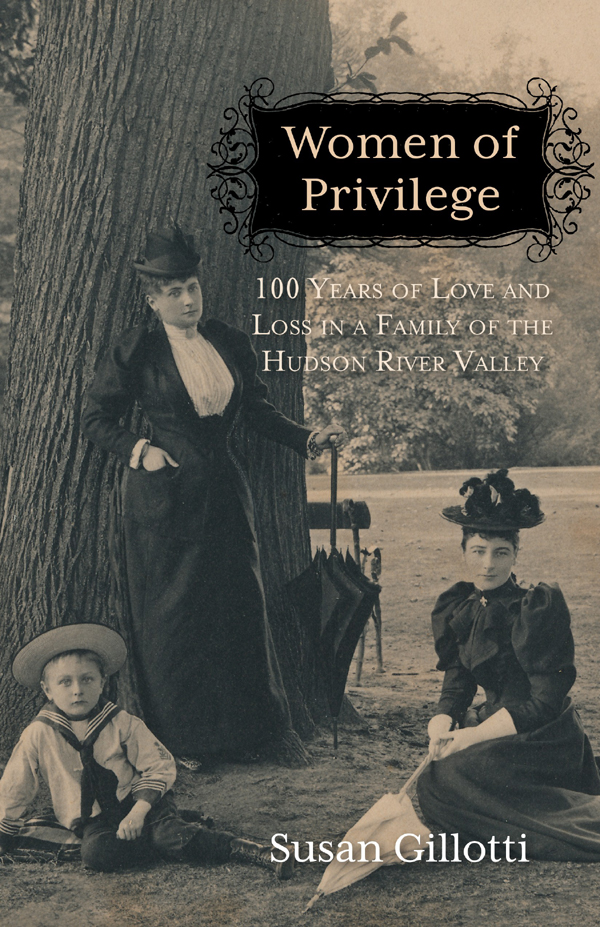

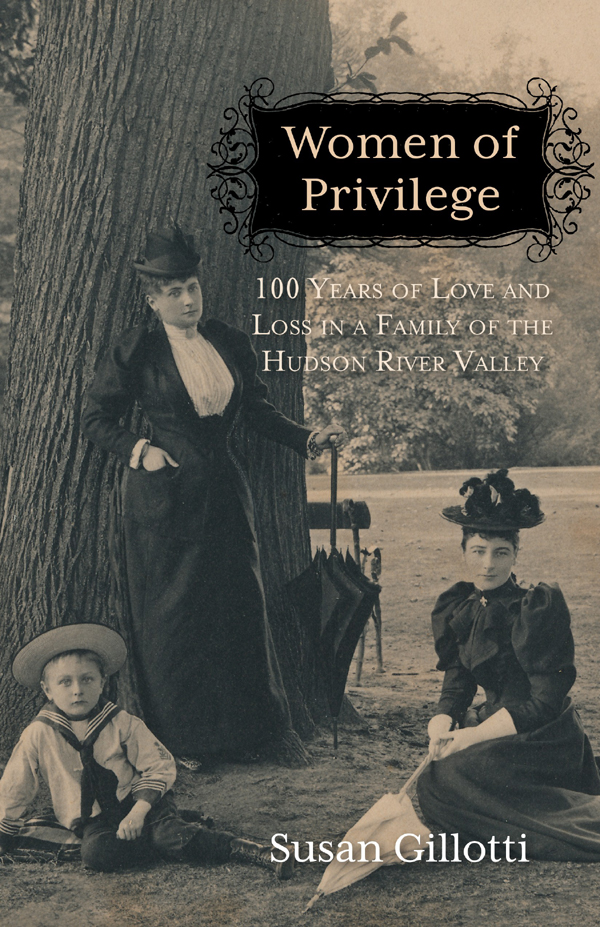

Women of Privilege

100 Years of Love and Loss in a Family of the Hudson River Valley

Susan Gillotti

Academy Chicago Publishers

Published in 2013 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60654

2013 by Susan Gillotti

First edition.

Printed and bound in the U.S.A.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Cover: Fanny Schieffelin Crosby (standing), Maunsell Schieffelin Crosby, Minnie Schieffelin (seated left to right), circa 1894.

All photographs courtesy of the authors collection.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Yale University Press for permission to excerpt from Beulah Parker: The Evolution of a Psychiatrist . 1987 by Yale University.

For Sheila and Judy

PREFACE

The Hudson River Valley extends along the east and west banks of the river from Manhattan to Albany. For many, its core is the section of river that runs for approximately fifteen miles north and south of Rhinebeck. Settled in the 1700s by Beekmans and Livingstons, it is a place where many descendents of the early settlers still live. It is their love of the land and the life stylequiet, nature-loving, unostentatiousthat keeps them there.

The Beekman Arms, in the center of Rhinebeck, claims to be the oldest continuously operated inn in the country. As one enters its dark, low-ceilinged tavern, it transports one to an earlier time. North and south of Rhinebeck are houses representing every style of American architecture from Colonial, Georgian, and Federal to Greek Revival, Italianate, and Late Victorian.

Grasmere, on Mill Road a mile south of the Beekman Arms, was not a grand house, but it was grand enough. Its history began with Janet Livingston, a granddaughter of Col. Henry Beekman, when she inherited 618 acres of land. She married General Richard Montgomery in 1773 and together they planned a house. Construction began, but the Revolutionary War intervened. Richard was killed in the Battle of Quebec in 1774 and after a few years, Janet wanted to leave. As a memorial to her husband, she planted a long driveway with locust seeds. Many of these seeds grew into beautiful trees. She moved north to Red Hook, to a house she named Montgomery Place, and Grasmere fell into the ownership of Peter Livingston.

The original house burned down in the 1820s. It was rebuilt as a red-brick mansion with white marble trim. In 1850, Lewis Livingston, Peters nephew, became the owner. He made further enlargements from 1861 to 1862, at the same time acquiring an additional 280 acres of farmland.

Sarah Minerva Schieffelin, my great-great grandmother, bought the 898-acre estate in the 1890s, when Lewis died. She was living in Manhattan at the time, expecting to stay in her Fifth Avenue house with her daughters nearby. But one thing led to another, and her son-in-law, Ernest Crosby, crossed the line with his political beliefs. Sarah felt certain that she could save her family embarrassment if she bought a country estate and offered it to Ernest as a home where he could write poetry and entertain his country neighbors rather than the socialists he preferred.

It didnt turn out as Sarah had hoped. For the next forty years, Grasmere experienced a number of family upheavals. The house was beautiful, and the farm prospered. Guests came and enjoyed the gardens and distant views. But money started to run out, and my grandfather, Maunsell Schieffelin Crosby, didnt invest in improvements as he should have. Eventually, after my mother inherited the house and land, it had to be sold. I didnt know about the upheavals. As a child, I was entranced by the stories my mother told about her childhood there, and I conjured up a world in which I, too, could have been a part.

It was only after my mother died in Florida, in 1995, that I learned the true story of what happened. The women who lived at Grasmere kept diaries, the earliest of which dates back to 1876. My grandmother, Elizabeth Coolidge, wrote letters daily. My mother, Helen Crosby, kept a diary, wrote letters, and kept a journal. She also wrote short autobiographical stories for the Famous Writers School, hiding her familys identity by calling herself Ann Pell. I discovered all of these documents in a closet. Attached to them was a note: For my daughters to read after I am gone. In these papers you will find answers to questions I know you have had.

I shipped the papers from Florida to Marthas Vineyard, where I lived at the time. Three years later, when Id finished reading everything, I realized Id been given a rare glimpse into the lives of privileged women who were searching for an identity and power in a cultural system dominated by patriarchy.

The world of my forebears has gone forever. But I am their legacy, a woman who more than once has wondered how I acquired the sense of entitlement that sometimes gets in my way. By having written this book, I now understand those influences better. Whoever we are, wherever we come from, we carry within us parts of those who came before.

CHAPTER 1

I have in front of me a photograph of my great-great-grandmothers drawing room on Fifth Avenue in New York. I dont know its date, except that it is more than a hundred years old. I do know that at that time, 665 Fifth Avenue was a five-story row house with twelve steps rising to its front door. Many of the houses on Fifth Avenue once had front stoops. I found a picture of the house in Burton Welless Fifth Avenue from Start to Finish 1911 , a photographic record of every building on Fifth Avenue from Washington Square to East 93rd Street. My great-great-grandmother, Sarah Minerva Schieffelin (Mrs. Henry Maunsell Schieffelin), is listed as the owner of the house that stood between East 53rd and East 54th Street. She lived there for many years.

My photograph of the drawing room shows that Sarah Minerva and her family lived a comfortable life. There is a cream and gold Steinway piano with a collection of scores on it. A large gilded mirror hangs opposite. The chairs and sofa are upholstered in silk and a white polar bear skin rug lies on the parquet floor. Sitting on a marble-topped table is a Meissen porcelain cockatoo, its head tilted downwards as if it wanted to eavesdrop. Happily, the cockatoo is now in my house in Vermont. It sits on a bookshelf next to an Abenaki carved bear. The cockatoo and the bear come from different worlds, just as I live in a world that is different from my maternal ancestors world.

The story of my family begins with Sarah Minerva Schieffelin, whose values left an imprint on those of us who followed. I came to know her through reading a diary she began on June 28, 1876. She was the devoted wife of Henry Maunsell Schieffelin, a scion of a successful importing firm. The diary begins as she and Henry, and their two daughters, Minnie and Fanny, are preparing to leave for an extended trip to Europe.

The purpose of the trip was to introduce Minnie and Fanny to the cultural treasures of Great Britain. They planned to visit important sites in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and England. Theyd booked passage on the Cunard Line which, beginning in 1840, offered private staterooms on scheduled passenger service across the Atlantic. Mrs. Schieffelin had written letters to friends living abroad announcing their dates of arrival in Dublin, Edinburgh, and London. Because Henry had earlier served as Consul General in Liberia, they knew many people in diplomatic circles.

Next page