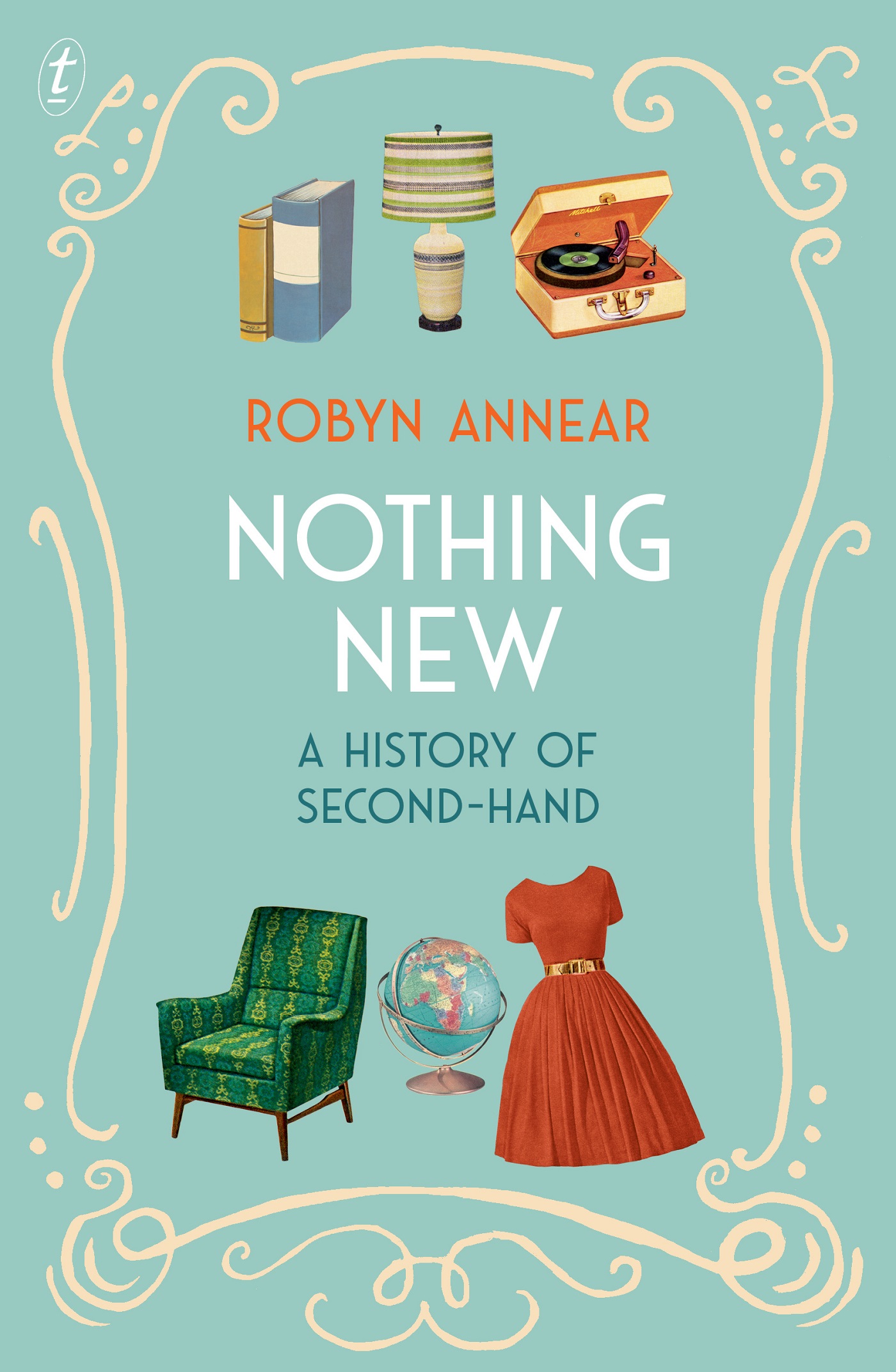

Given the way we live now, writes Robyn Annear, it would be easy to suppose that newness has always been venerated. But as this wonderfully entertaining short history makes clear, modern consumerism is an aberration. Mostly, everyday objectsfrom cast-off cookware to clothing worn down to ragshave enjoyed long lives and the appreciation of serial owners.

Nothing New is itself an emporium: a treasure store of anecdotes and little-known facts that will intrigue and enlighten the devoted bargain-hunter and the dilettante browser alike.

For Val Annear, my brilliant mum.

When one sees a crowd of ill-clad women with suit cases and sugar bags wending their way in subdued excitement to a hall in the afternoon one may be pretty certain that a jumble sale is there.

AGE (MELBOURNE), 1924

CONTENTS

One little flapper beamed with delight when she became the possessor of a pair of silver shoes for sixpence.

HERALD (MELBOURNE), DECEMBER 1925

Millie Tallis came up with the idea.

It was the winter of 1925 and St Vincents Hospital was looking to expand. A fundraising appeal was launched, headed by Melbournes lord mayor and a committee of worthies that included Sir George Tallis. Sir George had made his fortune as a theatrical impresario and his good lady wifebefore she was his wife, of coursehad starred, in tights and satin bloomers, as a comic-opera gem. Now the pair shone bright in the constellation of Melbourne society.

Over the course of several months, raffles were held and balls mounted; there was a car rally, a beauty contest, a telephone girls carnival, a brass-band extravaganzathe usual things. Also usual would have been a jumble sale, held over one or two days in a hall with room enough for trestle tables and the serving of tea. But the St Vincents committee had at its disposal something better than just any old hall: on the site of the hospitals proposed expansion stood the Cyclorama.

Forty metres in diameter, with a high, domed roof, the Cyclorama was built in 1889 to house a 360-degree painted panorama, which audiences viewed from a central platform. Its hard now to imagine how the Cyclorama ever rated as much of a thrill; the panorama, depicting one bloody tumult or anotherthe Battle of Waterloo, Eureka Stockade, the Siege of Pariswas changed only every few years. In any case, early in the new century, moving pictures had made a white elephant of the whole thing. What use then was there for a circular building, even (or especially) one surmounted with the crenellated faade of a castle? Other than as a pigeon loft, it served fitfully as a boxing stadium and as storage for stage props, then St Vincents acquired it with a view to demolition.

Lady Tallis and her husband had just returned from a motoring tour that took them through France and across the US, where theyd witnessed the popularity of second-hand shops run on charitable lines. Why not try something similar in aid of St Vincentsa shop, rather than a jumble sale? Lady Tallis took charge and, in christening the enterprise, paid a nod to its continental progenitor, le magasin doccasion. But while the French occasion here signifies bargain, it can also be used to mean opportunity. Did Lady Tallis mistranslate, or was it a knowing distinction she madeor even a small cross-lingual pun? Whichever, it came to pass that, for three months straddling Christmas 1925, the Cyclorama played host to the first ever opportunity shop.

Other peoples detritus calls to me. And from that siren song this book was born.

Op shops being my element, my first thought was to trace their origins, which led me to Lady Tallis and the bargain shops of interwar France. But second-handing, it turns out, stretches back and back across millennia. Common sense dictates that used must always have followed new. The archaic word handsel, denoting the first sale or use of a thing, posits the inevitability of successive sale or use. Innovation, kinship, trade, status, crime, migration, fashion, deathall have been timeless generators of second-hand.

In the dictionary, second-hand keeps company with

Given the way we live now, it would be easy to suppose that newness has always been venerated. But such a notion was almost unknown until late in the eighteenth century, and gained wide currency only during the twentieth. With the advent of consumerism, obsolescence supplanted re-use in the life cycle of things. Of course, second-hand goods didnt cease to exist but, with the exception of cars, the no-longer-new lost its value and was disregarded. Not just used but used up.

The second-hand industry has drawn the attention of academics in disciplines ranging from economics and marketing to fashion and textiles, history and sociology. Most seem to have approached the subject ethnographically, as observers of a repellent custom. As recently as 2015, one British academica geographer and social researcherwrote that the purchasing of pre-consumed used clothingis perceived negatively as undesirable. Good griefnow he tells me.

My mum had no sisters, only girl cousins who were just her age and size, which pretty much ruled out hand-me-downs. But, Depression and war-time privation notwithstanding, her mother contrived to keep her smartly dressed. Not being one of natures needlewomen, Gran outfitted her little girl in quality second-hand from market stalls that promised their stock came exclusively from homes in the better suburbs.

If Mum had no problem with second-hand, Dad surely did. Thanks to a stiff-necked upbringing, he was rigid about manyto be honest, mostthings. Hed been raised alone by his mother, whom department stores employed to inflict the cruel art of corset-fitting, and who impressed on her boy that only new was good enough. No second-hand for us, then.

Not that second-hand was really an option in the sixties and seventies, unless you were a charity case. Ours being a fissile nuclear family, cousins didnt feature, and even if they had, Dads standards would have ruled their (or anybodys) cast-offs unwelcome. But new clothes were pricey and money was tight. Luckily Mum had trained as a dressmaker: equipped with a sewing machine and no end of resourcefulness, she kept us decently, if not fashionably, clad.

The following year I changed schools. Life up till then had confined me to the burgeoning suburb of Doncaster, a former orcharding district subdivided into quarter-acres and planted with brick veneerstwelve miles by bus from the centre of Melbourne. Now, for my final year of school, I switched to a college in the CBD. Most of the other students were aged in their twenties or older, returning to study so as to qualify for a free university education. I was a young sixteen. I knew by heart every song by Rodgers and Hammerstein and not one of the Rolling Stones.

That year was, lets say, an eye-opener. Besides discovering the possibilities of the adult world, I began to glean hints of my own character. The temptations set before me were three: sex, drugs and second-hand.

There was a shop in Swanston Street that sold smokers paraphernalia, incense, Indian skirts smelling of jute, T-shirts printed with profanities and, upstairs, racks of vintage clothing. I have a recollection (smoke-hazed) of floaty, bias-cut, nipped-waist and knife-pleated garments dating from the 1920s to the 50s. I liked to look and linger, but the prices were beyond me.