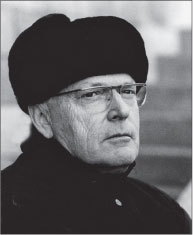

Douglas Boyd is probably the only British author who has confronted the KGB while enduring solitary confinement in a Stasi interrogation prison. He studied Russian language and history while training for signals interception at an RAF base in Berlin snooping on Warsaw Pact fighter pilots over-flying East Germany and Poland. Back in civilian life, he spent several years at the height of the Cold War dealing with Soviet bloc film and TV officials, some of whom were undercover intelligence officers.

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

April Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Voices from the Dark Years

The French Foreign Legion

Normandy in the Time of Darkness

Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass

De Gaulle: the Man who Defied Six US Presidents

Lionheart

The Other First World War

This book is dedicated to all the political prisoners detained in the Stasis Lindenstrasse interrogation prison in Potsdam, and to our predecessors who suffered there under the KGB 194552 and under the Gestapo 193345

CONTENTS

I n the early summer of 2011, during the run-up to the 2012 Russian presidential election, I was contacted by a very successful international businessman from one of the former Soviet satellite states. Highly intelligent and fluent in several languages, he might well have struck me as a top-rank KGB First Directorate officer, had this been in the Cold War period. For the sake of his anonymity, lets call him Dmitri.

From his first telephone call, it was apparent that he had done his homework: he knew a lot about me and my writing. This was borne out when he travelled from the Swiss frontier with his very beautiful Russian wife Sofia expressly to visit me at my home on the other side of France with a strange suggestion. It was that The Kremlin Conspiracy should be published in Russia. I replied that surely Russians knew their own history, so what would be the point?

Sofia had studied Russian history at Kazan University. According to her, the only history taught in Soviet schools and universities during the period of the USSR was what corroborated Marxist theory! Things, she said, had not greatly improved since and, although a history graduate, she had learned much from the first edition of my book. As to me finding a publisher in Russia, I explained that there were agents for that sort of thing, that not many books were translated into Russian, and

Not having made all his money by letting problems get in the way of business, Dmitri said that he would help. The conversation was mostly in English, but in one of the Russian exchanges, I heard him mutter to Sofia, Lebedev. The oligarch father and son Alexander and Yevgeny Lebedev were famous as British press barons, and Alexander had recently been seen live on a Russian television channel chat show punching another participant several times for disagreeing with him. There were rumours that Lebedev Sr intended to compete with Putin in the coming presidential elections motive enough, Dmitri thought, for him either to publish my book in Russia, or arrange for a friend to do so. All that was necessary at that stage would be to supply a copy of the book with a synopsis and a specimen chapter in Russian. I explained that, although I could translate from Russian into English, I could no longer pretend to be competent in the other direction. No problem, said Sofia, who had been a journalist after leaving university. She would do it for me.

Which chapter? I asked. Both of them said, Oh, the last.

Chapter 27 the last in the first edition entitled The Making of the President, Russian Style, explores the most likely origins of Vladimir Putin, which are not at all what his official biography would have us believe. I suggested that having it published in Russia would hardly amuse Mr P., so we might all end up drinking polonium cocktails, like Alexander Litvinenko in 2006.

Dmitri said he didnt think that was a real danger and shortly after their visit I received an email from Sofia which began:

I went through her draft and asked for one or two points to be changed. Back came the fair copy. The next problem was getting it to Lebedev Sr because it is not easy to reach the super-rich. I asked a very persistent Russian friend living in what they call Londongrad for help. Within 24 hours she had dug up the address of Lebedevs private office. The book, synopsis and specimen chapter were despatched by registered post. I waited for a reply, which did not come. Rumours, which may or may not be true, had it that some sort of deal had meanwhile been cut and Lebedev had changed his political plans, presumably with some kind of quid pro quo. I never did find out whether Dmitri and Sofia had been actors in a scenario masterminded by him.

Its a very Russian story. As Winston Churchill said on the BBC in October 1930, Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Nothing changes.

Douglas Boyd

South-west France

Autumn 2014

E x-prisoners never forget the first time the cell door slams shut and is bolted from the outside. The absence of a handle on the inside symbolises the loss of freedom. To that, the Judas-hole, through which the guard can see but the prisoner cannot, adds loss of dignity and privacy. Identity shrinks to a cell number. Cell No. 20 in the Stasis Lindenstrasse interrogation prison in Potsdam measured just three paces by four, the floor space encumbered by a bed, a table and a chair. There was no running water. A smelly lidded bucket served as my toilet, emptied by a trusty during my brief exercise periods in a cobbled yard, where every step was watched by a guard with loaded sub machine-gun on a platform atop the 4m-high wall. To complete a tour of the yard took thirty normal paces.

Once a day during my solitary confinement, I was brought a tin jug of cold water and a chipped enamel basin in which to wash my face and try to clean my teeth. In the absence of any towel, I used my underwear, washing it every few days in the same bowl and drying it on the central heating radiator. Once a week, I was escorted to a warmish shower and given a small towel, already damp from previous users. Every two or three days I was given a mug of tepid water and a safety razor with much-used blade with which to shave. Three times a day a warder brought food: a slice of black bread and some unidentifiable brown jam with ersatz coffee for breakfast and noodles or potatoes with something like a meatball for lunch. Supper was even less exciting. When I stopped eating in protest at my detention, the prison governor was concerned enough to come and eat some of my lunch himself, explaining that it was the same food he and the guards ate. I started eating again to show that I was prepared to behave, if only someone would pay attention to me.

Always wearing a cheap civilian suit, my Stasi interrogator Lt Becker would arrive at any hour of the day or night and repeat the same questions to me about my duties at RAF Gatow, the names of my fellow servicemen and my German friends in Berlin. The questions were interspersed with his lectures on how good life was in the GDR, where I could apply for citizenship and be guaranteed a job as tractor driver on a collective farm in Saxon Switzerland, with a pretty blonde partner thrown in as part of the package. When I queried the automatic availability of the blonde, Becker assured me that she was there. An obedient party member was how he described her. The price for the job and the girl was to show that I was truly vernnftig (reasonable) and answer all his questions. I might not have been quite so courageous had I known that, under paragraph eight of the GDR law dated 11 November 1957, the penalty for my crime of entering the country illegally was a sentence of up to three years in a labour camp.

Next page