With special thanks to

the Womens Engineering Society

in their centenary year

By the same author

William Armstrong: Magician of the North

La Vie est Belle

Coastal Living

Amazing and Extraordinary Facts about Jane Austen

Cragside, Northumberland: a National Trust guide

For my granddaughter, Isobel Seren Orr the future

Contents

With thanks to

Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET)

and Loughborough University for their support

Introduction

This book began as the story of one intriguing, enigmatic and inspirational character: Rachel Parsons daughter of a volcanic genius, scion of an Irish earl who in the 1840s built the largest telescope ever seen. Rachel was the founding president of the Womens Engineering Society. It was during her presidency of the society, immediately after the First World War, that Rachel met Caroline Haslett, an equally extraordinary woman of a very different kind. From a lower-middle-class background of Victorian strictness, Caroline would go on to become the pre-eminent female professional of her age and mistress of the great new power of the twentieth century: electricity.

The idea of exploring the parallel lives of these two largely forgotten women looking at how their paths converged and diverged, and comparing their challenges and successes was irresistible. What I hadnt anticipated was the number of other amazing individuals who, along the way, would clamour to get into the book. For the Womens Engineering Society was a magnet for many of the ambitious and intellectual women of the 1920s and 1930s who sought to express themselves and earn a living outside writing or the arts. As well as securing the vote and the right to stand for Parliament, women were making some progress in law, medicine and other areas, but those with technical, mathematical or scientific interests had a harder struggle. The Womens Engineering Society and, later, the Electrical Association for Women, drew them together in a common purpose, opened up new opportunities, and encouraged them to make alliances across boundaries of wealth, politics and class.

It wasnt all plain sailing, of course. While showing the effectiveness of a strong body of women working together, the Womens Engineering Society also exposed the weaknesses of such an organisation, as illustrated by the rift that occurred in the mid-1920s, and by the estrangement of Rachel Parsons from her former colleagues. In a forerunner of todays familiar assassination by social media, women who stepped outside the boundaries of normal female behaviour were often subjected to ridicule and suspicion; they reacted by ignoring such treatment or asserting their independence in diverse ways, with many remaining single or having same-sex relationships.

Engineering covered a broad range of disciplines at the time as remains the case now, more than ever but in 1919, when the society was founded, it brought together those women who had contributed to industrial production and related activities during the war and felt angry and disappointed at being, as some put it, thrown on the scrapheap afterwards. Some were trained in particular skills, others absorbed skills along the way, or became brilliant managers, but all had had their eyes opened to the advantages of social and economic liberation. They felt motivated to act not only for their own sakes but also to avoid the waste of human talent that the ejection of women from industry implied.

Achieving equal pay with men was an important goal of the Womens Engineering Society from the start, but it was not only financial security and public recognition of their achievements that mattered to these women. In the wartime munitions factories, the positive effects of supporting female workers in all aspects of life had become clear. To sustain a strong and resilient workforce, high priority had been given to healthcare and good nutrition, including the introduction of canteens; special provision had been made for pregnant women and mothers of young children, including subsidised childcare schemes. Effort had gone into providing good-quality accommodation for women working far from home, along with sporting and leisure facilities, which offered the workers plenty of opportunity to meet people from outside their usual social sphere. Training and education had been implemented on an unprecedented scale for female workers, who had shown that they could excel in many areas; this was particularly significant at a time when only a tiny proportion of university students in all subjects were female, and the number taking mathematics and engineering subjects was vanishingly small. Taken together, these elements might have been seen to prefigure a feminist utopia until, when the war ended, it all started to go badly wrong.

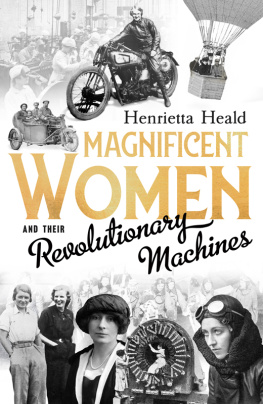

The magnificent women who populate this book called themselves engineers, but their revolutionary machines were more than simply mechanical objects such as cars and boats and planes. Through their achievements at work and their campaigns to promote womens liberation born of the fight for the franchise and their own wartime experiences they prepared the ground for a social revolution that would put fair and equitable treatment of the sexes firmly on the political agenda. It amounted to a vibrant wave of feminism that, until now, has largely eluded the attention of historians.

ONE

Leading Ladies

On 23 June 1919, seven exceptional women gathered at 46 Dover Street in Londons Mayfair to do something that had never been done before to create a professional organisation dedicated to campaigning for womens rights. It was the official birth of the Womens Engineering Society, the fruit of an idea conceived several months earlier, as the guns of the Great War fell silent.

Each of the seven women was required to sign a document giving her name, address and marital status. Outside the inner circle, but keeping a eagle eye on its every move, was Caroline Haslett, a young electrical engineer and former suffragette, who earlier that year had been appointed the societys first administrator.

At the head of the table was Katharine, Lady Parsons, a commanding and charismatic figure, who gave her address as 6 Windsor Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne. Katharine was the wife of the revered engineer Sir Charles Parsons, whose development of the steam turbine had changed history by revolutionising the propulsion of ships and providing the means for the cheap and widespread generation of electricity. In 1927 Charles Parsons would be admitted to the Order of Merit, an honour in the personal gift of the sovereign.

From the early days of

The first signatory in the group was Eleanor, Lady Shelley-Rolls, a keen balloonist, the sister of the late Charles Rolls, with whom she shared a passion for speed and danger. Charles had partnered Henry Royce in a fabulously successful automobile production business, set up in 1906, until he was killed in a flying accident four years later, at the age of thirty-two. After the death of her two remaining brothers during the war, Lady Shelley-Rolls became heir to a large fortune and the Hendre, the family mansion and estate in Monmouthshire. On her marriage in 1898 to Sir John Shelley, a great-nephew of the poet Shelley, the couple changed their name to Shelley-Rolls.

Next page