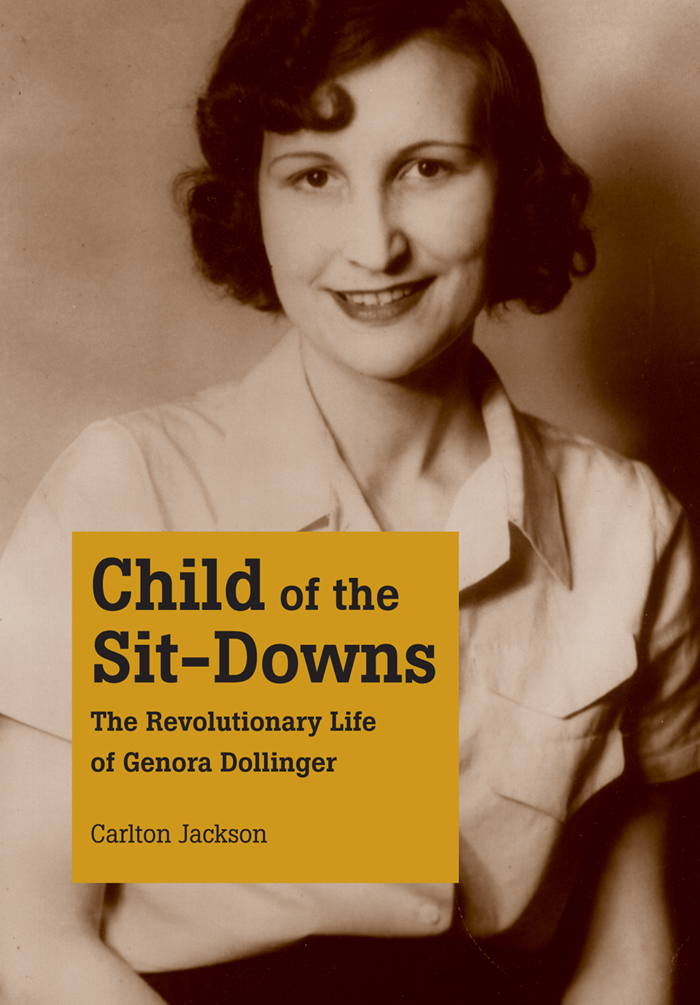

Child of the Sit-Downs

Child of the

Sit-Downs

The Revolutionary Life of

Genora Dollinger

Carlton Jackson

Kent State University Press  Kent, Ohio

Kent, Ohio

2008 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2008001510

ISBN 978-0-87338-944-0

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jackson, Carlton.

Child of the sit-downs : the revolutionary life of Genora Dollinger / Carlton Jackson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87338-944-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Dollinger, Genora Johnson. 2. Women labor union membersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Automobile industry workersLabor unionsUnited StatesHistory. 4. Automobile industry workersUnited StatesBiography. 5. Labor unionsUnited StatesBiography. 6. Womens Emergency Brigade. I. Title.

HD6509.D65J33 2008

331.88'1292092dc22

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acknowledgments

Many people helped me to research and write this biography of Genora Dollinger, and I must express my appreciation to them. First, at the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Reuther Library at Wayne State University in Detroit, Walter Lefevre, Patrice Merritt, Margaret Raucher, and Mary J. Wallace were helpful. Paul Gifford of the University of Michigan, Flint; William Glenn, Stony Brook University; Julie Harrada, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and David Kessler of the University of California-Berkeley found some much-needed materials, for which I am grateful. Thank you.

At Western Kentucky University I received considerable help from research grants and summer fellowships. I thank each member of that universitys committees for their help. My graduate assistants proved so indispensable that I can truthfully say that this manuscript could not have been completed without them. John Paul Hill, Jennifer Kretzer, Melinda Jayne Squires, Evan Lambeth, Christopher George, Mary Bokkin, Jonathan Chilcote, and Phil Shaw provided unstinting help, cooperation, and encouragement. I thank also the former and present chairs of the WKU history department, Richard Troutman and Richard Weigel, for their support of this project. Nancy Marshall of the WKU library was extremely efficient in acquiring much-needed materials, as were Debra Day and Selena Langford of WKUs interlibrary department. WKU librarians Alan Logsdon and Olivia Fruit helped in the research, and I thank them. Professor Lowell Harrison of WKUs history department read the entire manuscript and gave useful advice. My friend and colleague Lou-Ann Crouther of the WKU English department gave the manuscript an extremely close reading and helped immensely with grammar, punctuation, and organization. I am most grateful for her assistance.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the assistance that came to me from Sol Dollinger, Genoras husband of fifty-one years. (Sadly, Sol died on September 12, 2001.) At my invitation, Sol read the entire manuscript. Although he corrected me on some factual matters, and while we did have some differences of opinion, at no time did he ever tell me how to write this biography (I cannot say the same about some of Genoras critics). When I interviewed Sol in 1997, I asked him what kind of biography he would like to see of Genora Dollinger. His answer was, An honest one. This, to the best of my abilities, I have done.

Many other individuals besides Sol Dollinger supplied me with information. Their names appear in the text and in the endnotes. I thank all those persons who knew Genora personally and willingly talked to me about her.

Finally, I take pride in thanking my lovely family for their continued support of my publishing endeavors: my daughters Beverly and Hilary; sons Daniel and Matthew; sons-in-law Steve and Arthur; daughters-in-law Ling and Elaine; Grace; my grandchildren Colleen, Megan, Katharine, Travis, Patrick, Austin, Liam, Rowan, Carlton, David, Finn, and Alec. And, foremost and always, Pat.

Preface: Genora and Luther

Writing about the relatively unknown nineteenth-century politician Felix Grundy, historian Joseph H. Parks says, The stories of the lives of the so-called great men of the nation have been told and re-told, but little has been done toward giving due credit to those who made them great. Leaders do not spontaneously spring into national prominence. They owe much to those lesser figures who, for the most part, remain behind the springs of action.

While Genora Johnson Dollinger would not have liked to be referred to as remaining behind the springs of actionalmost always thinking of herself on the cutting edge of eventsthat is essentially the part she played in matters of unionism and feminism. She never became a forerunner in either movement, but she assisted enormously those at the very top. Who were they? The list includes John L. Lewis; Norman Thomas; Betty Friedan; George Meany; Owen Bieber; the three Reuther brothers, Walter, Roy, and Victor; and several other luminaries. Genora helped these people to get to the top of the list and to stay there.

If Genora helped the top to acquire and retain power and influence, her contributions also traveled in other directions. She could meet Norman Thomas at ten in the morning and John Doe at noon and be equally comfortable with both. She could relate not only to the rich and famous but to the common worker as well. Perhaps she could be called a pivotal figure between what was often intellectual unionism and real or practical unionism.

I raise these points because my father, Luther Jackson, was a coal miner in Alabama, and, like Genora Dollinger, he was a worker, not a theorist or intellectual. The two of themand they never did meet each otherwere the strongest of union people. In the house where I grew up, Jesus Christ came first, followed closely by John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers of America, not all that much separated from the United Automobile Workers, the union with which Genora was most closely associated. As Lutherand perhaps Genora, too, at least in her earlier yearsmade his way to and from work each day,

Neither Genora nor my father ever finished high school, and neither was born into the kind of family that garnered any kind of admittance into the world of philosophical adjudications of unionism or labor movements or, for that matter, any kind of academic and intellectual pursuits. She fought and gouged her way into whatever program she was espousing at any particular moment, making her in a real way a professional reformer.

Luther and Genora were born worlds apart: Alabama and Michigan. Yet their basic beliefs about the laborer and his or her importance in the world of workers were more in agreement than not. Although my father would not have worried himself about the scholarly nuances of the labor movement itselfat least as it was expressed in paradigmatic terms by experts all over the country and, indeed, the worldin reality, at least during the first part of her career, neither did Genora Dollinger. Her approach to the labor movement was pragmatic, head-on, even in-your-face, much like Luthers. They were the rank and file of the union, the heart-blood of the labor movement, the very people to whom theorists and philosophers seemed initially to ignore and then ultimatelyand many times, it seemed, grudginglyhad to pay some attention.

Kent, Ohio

Kent, Ohio